This article is a translation from the German. Klicken Sie hier, um den Artikel auf Deutsch zu lesen.

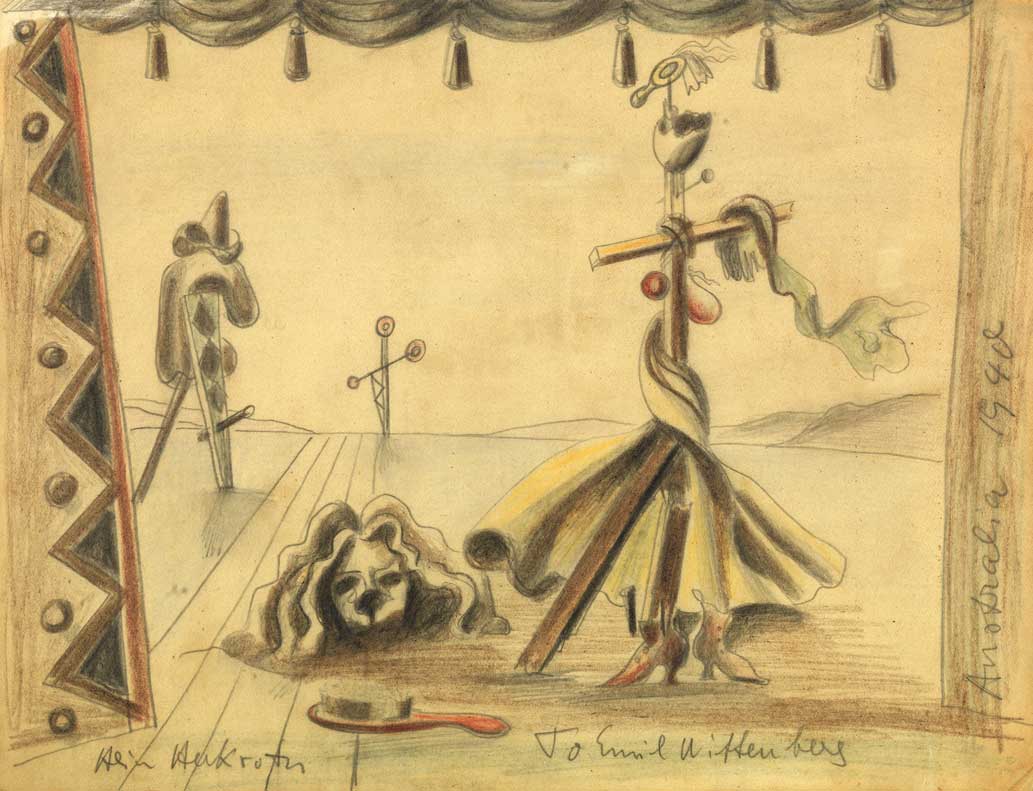

The name Emil Wittenberg has been quite familiar to me since my time at the University of Vienna (2006-2009), where I completed my dissertation on Hugo Wiener (1904-93), the Jewish composer and writer of cabaret programmes. Between 1935 and 1937, Emil was responsible for set design in the small Viennese cabaret ‘Cabaret ABC’ a handful of times. At that same time, the young actress Cissy Kraner (1918-2012) - who later married Hugo Wiener – was performing in her first roles there. Throughout the course of writing my dissertation, I spoke with Cissy extensively. When I met her, I was 23 and she was 88 years old! But she had a phenomenal memory and for years, she shared with me detailed information about her long career as an artist. After I finished my PhD in 2009, we continued to meet up frequently until she died on 1 February 2012 at the age of 94.

Cissy Kraner’s career, which lasted for over 70 years, began in Vienna in the 1930s. Cissy was born on 13 January 1918 in Vienna. As a child, she already knew that, above all else, she wanted to be an actress. Her parents didn't like the idea at all – they wanted their daughter to train for a proper job and get married. But young Cissy had a mind of her own: she left school at 14 and began to train to become an actress.

Cissy Kraner in 1937.Image reproduced with the permission of Herbert Holzinger.

Cissy Kraner in 1937.Image reproduced with the permission of Herbert Holzinger.

After Hitler invaded Austria in March 1938, Cissy accepted the offer made to her by Jewish composer, Hugo Wiener. She accompanied him and an ensemble of singers and dancers to South America for a guest performance – which ultimately turned into 10 years living in exile in Colombia and Venezuela. Cissy was young and full of energy, in contrast to her significantly older and calmer counterpart, Hugo, but even in the first few weeks they grew closer and closer. After a time, they became a couple.

Not long after, Hugo received terrible news: his entire family, who he had had to leave behind in Vienna, had been murdered. Hugo tried as hard as he could to rescue his parents, his sister and his brother-in-law by getting them visas for South America, but to no avail. In November 1941, they were all deported to a camp in Kaunas in Lithuania and shot immediately upon arrival. Young Cissy could sense how desperate and devastated Hugo was, and she consoled him. And their relationship deepened.

The guest performance that had begun in Bogotá was so successful that they continued to perform in many other cities across Colombia. Ultimately, the troop split up, as some of the dancers left to pursue other ventures. Cissy and Hugo decided to carry on alone and, with great persistence and much hard work, they built a new life for themselves in Caracas, the capital of Venezuela. The years that followed were some the busiest of their entire lives: they had to start over entirely and both worked multiple jobs at the same time. They married in 1943 and after the war ended, they returned to Vienna. In 1950, they joined the cabaret ‘Simpl’, where they spent almost 20 years, launching a successful international career spanning over four decades.

By May 1993, Cissy and Hugo had been an unstoppable team on stage and in life for over 50 years, but their brilliant career was brought to an abrupt end with Hugo's sudden death at the age of 89. In order to continue sharing their joint work with audiences, Cissy began performing accompanied by her colleague Herbert Prikopa (1935-2015) on piano. After a serious accident at home, Cissy ended her stage career in 2005 at 87 years old.

And a year later, I met her. Because Cissy was so full of energy I was slightly daunted by the prospect of meeting her for the first time, and I was a bit nervous. But my worries were unfounded: we connected right away and got along very well. Over the next few years, I visited her often and she answered my questions with great accuracy – and sang me old songs from her first years on stage.

I was particularly honoured to have Cissy attend my PhD ceremony in the University of Vienna's ceremonial hall as my guest of honour. That was the greatest gift she could have given me – because by then she was close to 92 years old! I continued to visit her often after that, and in spite of her age, her death two years later was still a big shock to me because she had been with me for much of my studies and I owe her so much.

Of course, I continued to spend a lot of time researching Cissy and Hugo and, because there are many things I don't know about their lives, I still stumble across surprises. Above all this: among Cissy's correspondence, I found 74 letters from Emil Wittenberg, written between March 1936 and July 1966.

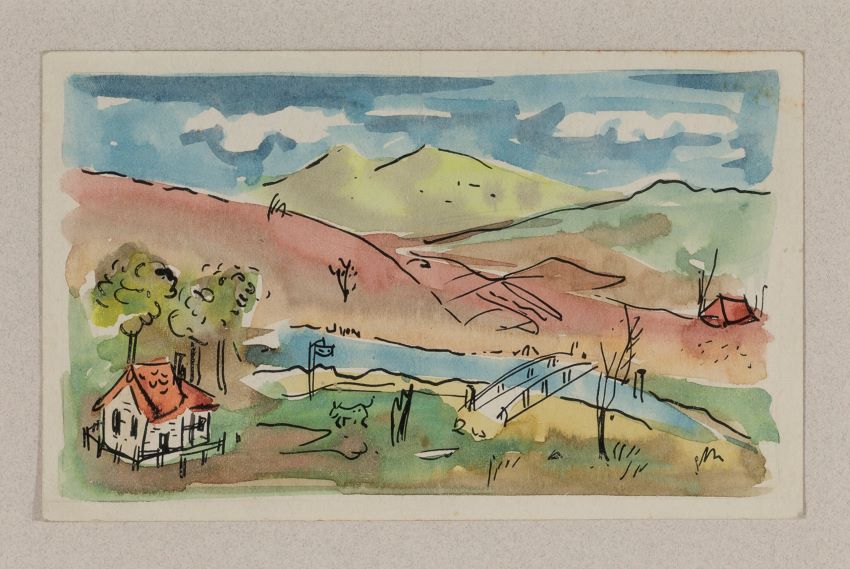

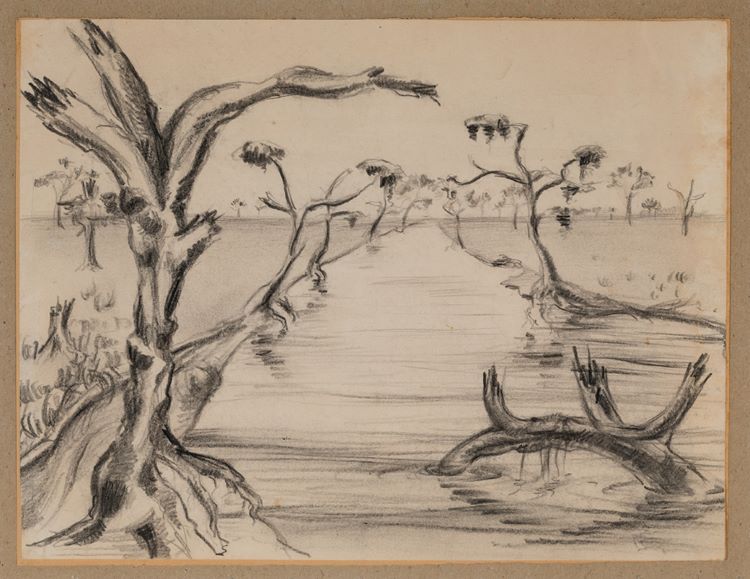

An untitled sketch of trees by a river.

An untitled sketch of trees by a river.

Emil, who had taken over his father’s company as an interior designer, was frequently engaged as a set designer at the ‘Cabaret ABC’, where Cissy performed in three different programmes during the 1935/36 season. The two became a couple and from around autumn 1935 until the end of 1937, their relationship saw many highs and lows. It’s clear how important Emil was to Cissy from the fact that the two remained in close contact even after their relationship ended, and that she kept these 74 letters until the end of her life.

I spent many weeks of Vienna’s COVID-19 lockdown (2020-22) reading them. The journey through time that these letters took me on was incredibly moving, as was all the information I learned about Emil's life, personality and what happened to him. Though he and Cissy were no longer a couple after December 1937, they continued to write to each other. Across continents, they remained in written contact until Emil's premature death on 26 December 1966.

While reading the letters, I also spent some time researching Emil Wittenberg online. That’s when I came across the interview with his nephew, Martin Burman, in which he said that, unfortunately, he knew nothing about his uncle’s life in Vienna (1910-38).

In order to share the information I had with him, I reached out to the ‘Stories from the Dunera and Queen Mary’ website and, to my great surprise, Seumas Spark responded in just a few hours. I told him about my research and he put me in contact with Martin right away.

And so, from far away Vienna, I was soon able to send to Melbourne a summary of the information I had gleaned from Emil's letters to Cissy, which reveal much him and his life. I am very happy that I've been able to provide new information about Emil Wittenberg and that I have met some wonderful people thanks to my research.

What the letters tell us about Emil and his life in Vienna:

Emil Wittenberg trained as an interior designer and began working in his father’s company at the age of 14. It was chance that brought Emil to the theatre; several times between 1935 and 1937, he had great success as the set designer in the small ‘Cabaret ABC’. Unfortunately, as he highlights in his letters, this was to the detriment of his other work and the financial gain from working in the theatre did not balance out this loss. The other aspect of it he found challenging was that it became clear after some time that many of the people working in the theatre were jealous and calculating, which made his work very difficult. He almost stopped enjoying it at all. Just as he was struggling with this situation, he met the bold and lively Cissy Kraner, who was performing in three programmes there. She was different from the others and made the theatre seem worthwhile to him once more. And in time, though their personalities differed vastly, they became a couple.

The first of Emil's letters are from March 1936, not long after Cissy's final role at ‘Cabaret ABC’. At that time, she was performing at the ‘Deutsches Theater’ in Vienna and, over the next few months, she played roles on various other stages across the city. There are another 13 letters before the end of 1936. They illustrate how Emil and Cissy spent a lot of time together and how he often picked her up at the theatre after her performances. Although he didn't always make a lot of money, he gave her gifts and was attentive, but Cissy sometimes comes across moody and capricious, seeming to expect support beyond what Emil was financially capable of.

It is clear from the letters that all of this took its toll on Emil's nerves: he was trying his hardest for Cissy and wanted to do right by her and create a harmonious life together. In December 1936, they separated for the first time as Emil began to see himself increasingly as a burden to Cissy, and didn't want to get in the way of her artistic career.

After a break of several weeks, there are two postcards from February 1937, and in May comes the first long letter since their separation in December. At this point in time, Cissy was performing in Scheveningen in the Netherlands with the ‘Theater der Prominenten’, a German language cabaret group. And from here onwards, Emil reports to Cissy, from miles and miles away, what has happened in his life in her absence.

The letters leading up to Cissy's return to Vienna in February 1938 reveal much about Emil's life, his day-to-day activities and his personality:

Emil comes across as very conscientious; he spends a lot of time looking after his grandfather, who is 86 and becoming old and weak, and in his workshop and in the office, Emil is very hard-working.

He is also employed at a range of different locations. He works as an interior designer, fitting out the apartments of well-off inhabitants of Vienna's villa neighbourhoods, and decorating the entry hall of a cinema for the premiere of a new film about Napoleon Bonaparte. It’s clear from the emphasis he places on it in his letters that his work as a shop window decorator for the Viennese hat company Korff is of particular importance to him. Korff has several stores throughout Vienna's expensive shopping precincts, and Emil's clever ideas for decorating the windows and presenting the products in a striking way contributes significantly to the company’s success and garners him praise and respect from his boss.

In his letters to her, Emil encourages Cissy when success is slow to come and offers financial support because of her low salary – though he is often not earning all that much himself. He is always polite to her, even when her tone becomes curt or she tells him off. In spite of all their differences, he is always there when she needs something, he gives her advice when she is in despair, and is excited when one of her roles on stage is a success.

When he learns that she has fallen in love with one of her colleagues in the ensemble, he's very hurt and needs some time to come to terms with the news. Still, he continues to hope that they will be reunited because, in spite of everything, he still really cares about her a lot. In the letters, he makes clear to her how much her behaviour has hurt him.

After some time, the dust settles, and the two are once again on friendly terms. Emil is looking forward to seeing Cissy in Vienna again soon so that the two of them, he hopes, will be able to give their relationship another chance. But his patience is put to the test: Cissy accepts one commitment after the next, which is very beneficial for her career, but not for her relationship with Emil, who is waiting longingly in Vienna for her to return. The original plan – a guest performance that was meant to last a few weeks – has now turned into half a year, and Cissy announces that she will also not come to Vienna for Christmas or New Year’s. Their problems snowball and in December 1937, they call off their relationship for the second and final time. In spite of this, Emil continues to offer Cissy support and a helping hand because he still cares about her and does not want to lose her friendship.

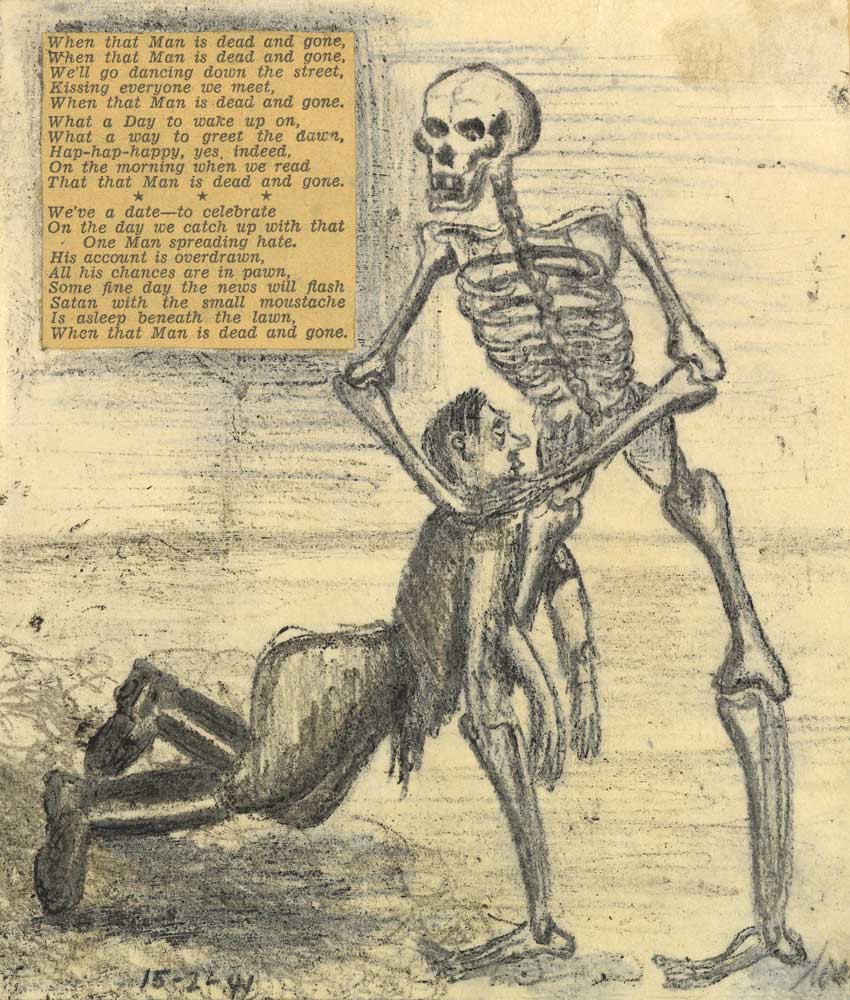

Throughout his letters, Emil also reports that, even in his daily life, he can sense that the Nazi Party is growing in size and that they are becoming increasingly open in their activities: while decorating a Korff shop window in June 1937, he watches as several troops of boys and girls from the Hitler Youth march and shout anti-Semitic slogans in chorus. Nine months after this, Adolf Hitler marched into Austria, and for Emil and all the other Jewish citizens of Austria, every day became a fight for survival.

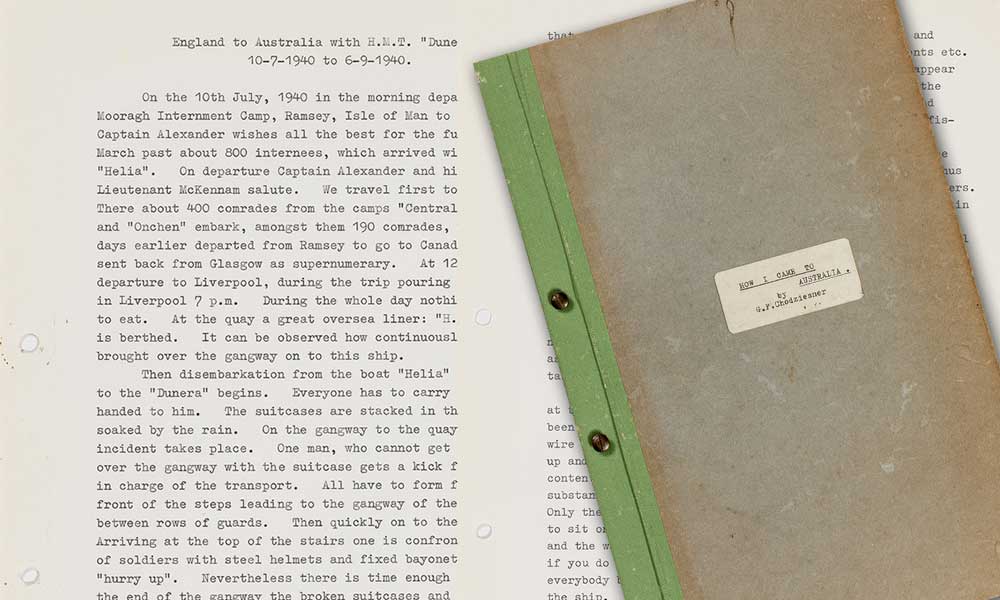

Letter from 1 October 1938

Emil tells Cissy what is happening in Vienna. Since autumn 1938, he has been applying for emigration papers and a visa, but no one from the United States has been in touch and his application to Australia was not approved by the Jewish Community Vienna (IKG). He has also been unable to get a visa to Colombia. In the meantime, Cissy, who is at that point still in Colombia, tries to get a visa for Emil.

Letter from 29 November 1938

Emil is thrown out of his apartment and the family's business is taken away by the Nazis. Emil is able to stay with his uncle, but he is constantly on the run. His letters become increasingly desperate as it is growing more and more difficult to emigrate.

Letter from 10 December 1938

Emil is running out of time. He only has until 31 December to leave Austria legally, but his applications for visas to Hungary and Australia have been rejected. He is desperate.

Letter from 21 December 1938

Emil tries to get a visa in any way he can; he queues up day and night, in minus 13-degree temperatures to get a permit from the authorities.

Letter on New Year's Eve, 31 December 1938

On the last day of 1938, Emil has yet to receive positive news about a foreign visa that would save him. Cissy tries to get him a visa for Panama.

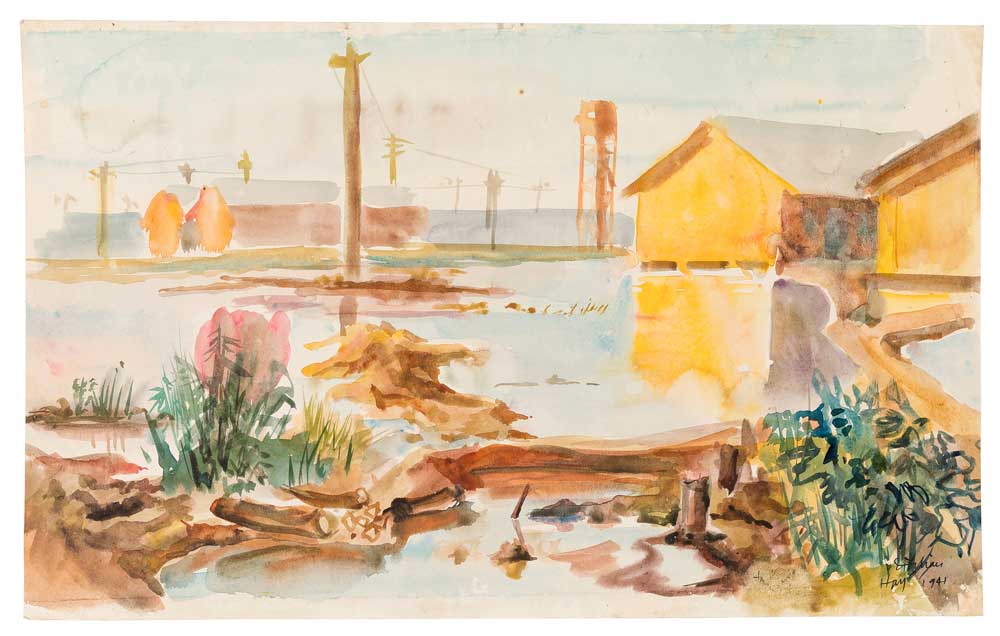

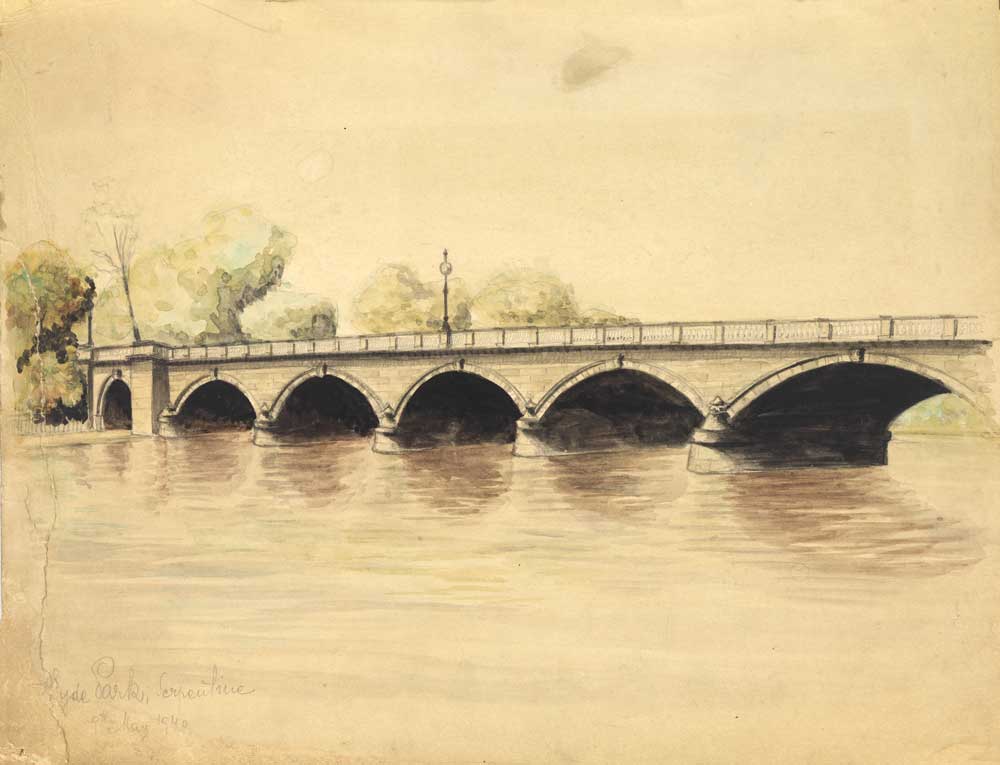

A sketch of Hyde Park completed during Emil's time in Britain.

A sketch of Hyde Park completed during Emil's time in Britain.

Letter from 6 August 1939

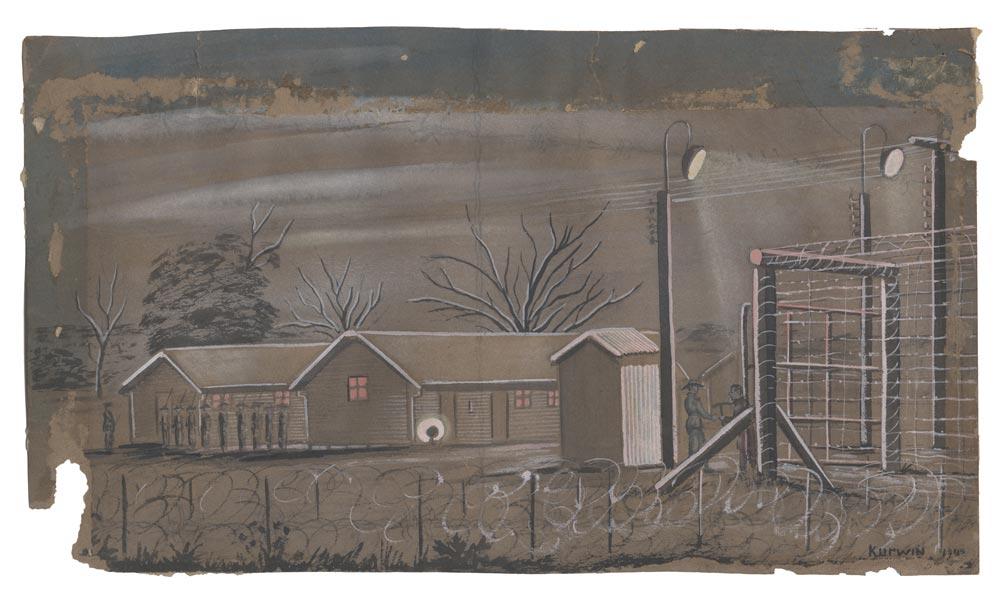

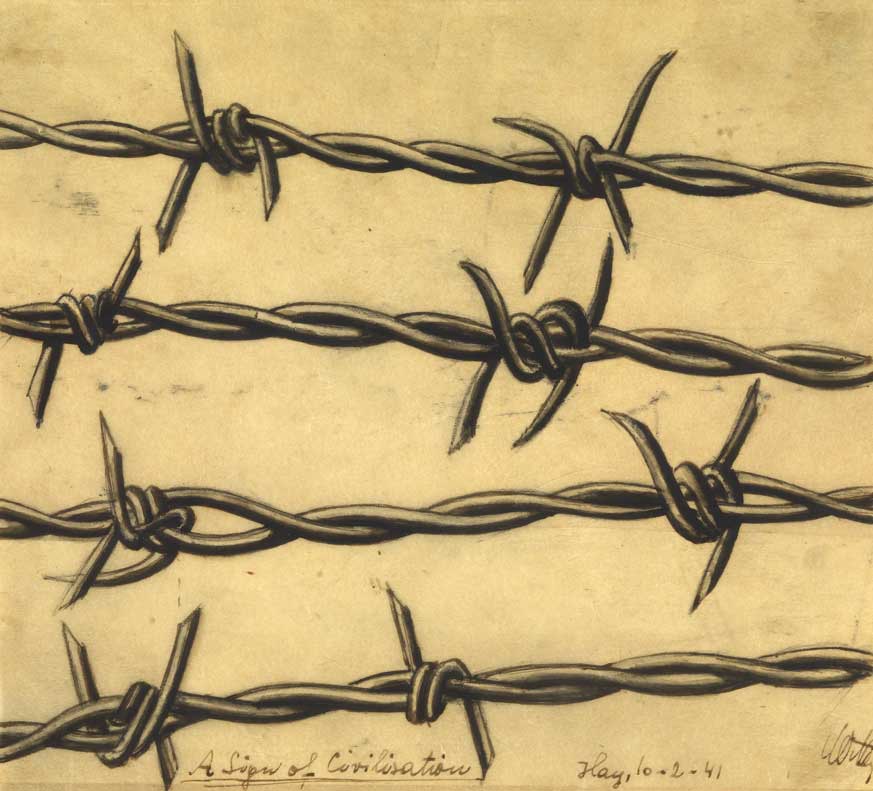

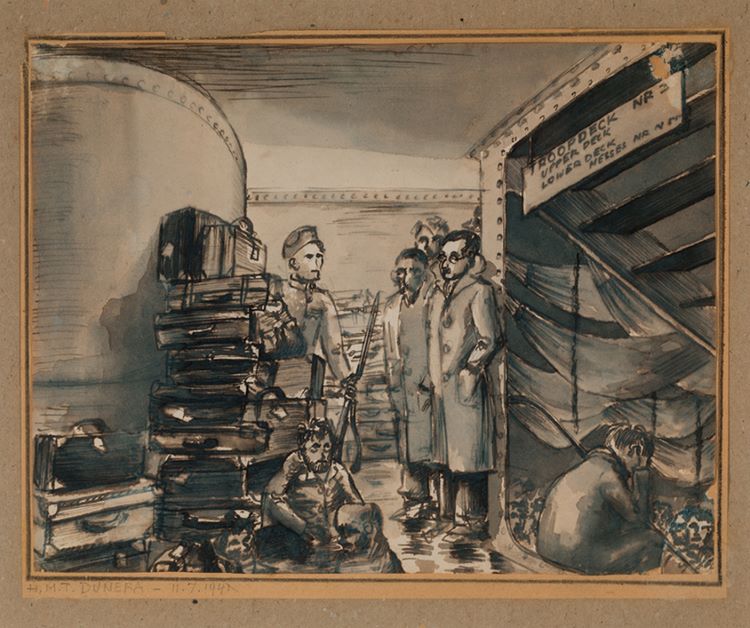

Emil's next letter does not arrive until the summer of 1939 – from London, after he fled to Romania with just the clothes on his back. From there, he was able to travel to London a few weeks later. In London, Emil manages quickly to establish a new life for himself, as a valued employee in an architecture firm. But he wants to continue on to Australia and applies for a visa – and this time, it is approved. But then there is a disastrous turn of events: not long before Emil is meant to receive his visa, he is classed as an enemy alien and deported, under terrible conditions, to that very place aboard the HMT Dunera.

And then the unthinkable happens: with the help of the Red Cross, Cissy finds Emil in 1941, in the internment camp in Tatura, and the two begin writing to each other again.

Letter from 10 November 1941

Emil tells Cissy nothing of his terrible experiences on the journey to Australia. Soon after arriving, he began working as a set designer in a theatre group in the camp. He is keeping a diary and is also learning English in order to become even better at the language than he already is. With the help of friends, he is trying to get a visa to the United States or Cuba.

Letter from 22 March 1942

Emil writes that Australia is a splendid country; living here is wonderful for him and he has made many new friends.

Letter from 16 October 1942

Emil is working as a solider in the Australian Army. He feels happy and satisfied in this wonderful country.

After this, there is a long break between letters. The next letter among Cissy’s belongings is from 1959.

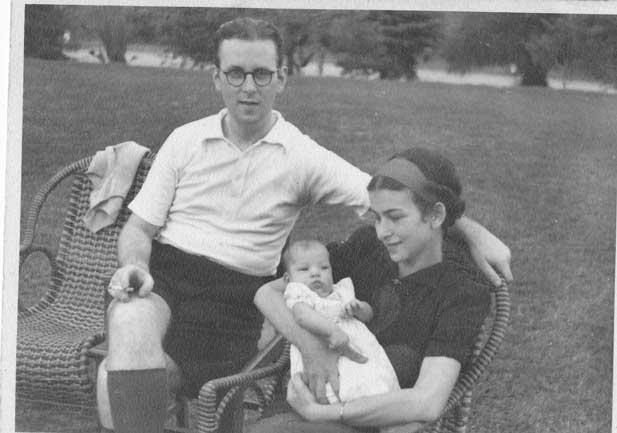

Emil Wittenberg, 1942.

Emil Wittenberg, 1942.

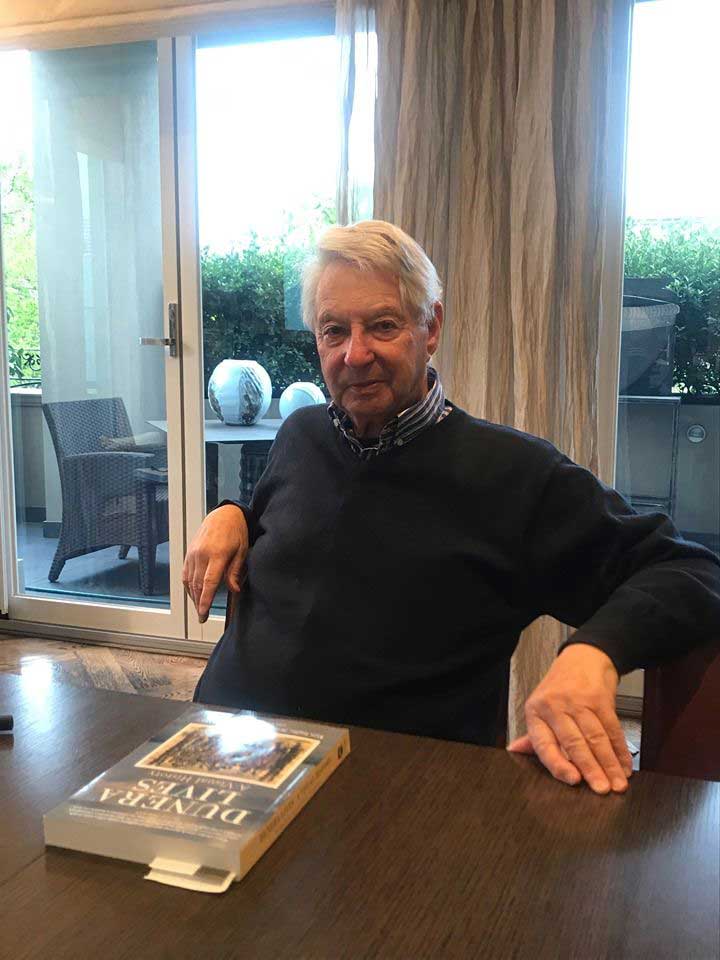

There are six other letters between this one and Emil's death on 26 December 1966. Though continents apart, Cissy and Emil's appreciation for each other is clear:

Emil writes often about how proud he is of Cissy and her great success with Hugo in the Viennese cabaret ‘Simpl’. Although the two of them are separated by thousands of kilometres, he feels a closeness to them and their performances – like he is able to share a small part of their lives. From friends, who have visited Vienna on their trips to Europe, Emil knows the songs that Hugo writes for Cissy, which she sings to audiences in Vienna in every revue. In many of the letters it is evident how proud Emil is that Cissy, in spite of all of her success, still has the good heart that he appreciated so much about her when they were together all those years ago. She always remembers his birthday and never forgets to send her warmest wishes, which makes him very happy.

Emil writes to Cissy from a holiday to sunny Queensland where, in Surfer's Paradise, 2000 kilometres from Melbourne, he enjoys the very different, summery climate. He goes on these trips with his wife Gerty, who is also from Vienna. After Emil's premature death, Gerty took it upon herself to maintain contact with Vienna: among Cissy’s belongings is a card addressed to her from Gerty.

Emil also endeavours to invite Cissy and Hugo for a guest performance in Sydney or Melbourne, but Cissy repeatedly turns down these invitations, saying that she and Hugo can’t make it work with their schedules. I don't believe that this is just a white lie to avoid meeting up after so many years: during this time, Cissy and Hugo spent almost the entire year performing their revues in the cabaret ‘Simpl’ and the few short weeks they had free during summer were spent recovering and preparing the opening revue for the new season in September.

Even in his second to last letter, Emil is asking, in vain, about their plans for 1967 and about whether a visit to Australia might be possible. Of course, at this point, no one knows that Emil will not live to see this year. What is clear from this second to last letter, dated 30 March 1966, is that, after many unsuccessful attempts, Emil and Gerty must have ultimately made the trip to Austria in 1965. He writes about seeing an operetta with Gerty at the Bregenzer Festspiele the previous summer – but otherwise makes no mention of what he did in Austria. Unfortunately, the letter does not say which cities the two visited on their trip, or whether they stopped in Vienna to meet up with old friends.

That means that, sadly, I cannot say for certain whether Emil and Cissy ever saw each other again; I have found no clear evidence one way or the other. I can well imagine that Vienna would have been one of Emil and Gerty's stops, though. Emil writes in one of his letters that he cannot imagine ever living in Vienna again because of the dark mark the Nazis left on the memories of his youth. And yet, in spite of all that, he writes that he would like to see the city again, as a visitor: all the houses and places that are close to his heart and that he remembers with fondness. So although Emil and Cissy remained in contact all those the years, across continents, when it comes to the question of whether they ever saw each other again – well, only they could answer that.

View the gallery of Emil Wittenberg

Karin Sedlak and Cissy Kraner in 2007. Image reproduced with the permission of Karin Sedlak.

Karin Sedlak and Cissy Kraner in 2007. Image reproduced with the permission of Karin Sedlak.

Author bio:

I studied German Studies and dramatics at the University of Vienna and completed my PhD in 2009. My dissertation was about the Jewish author Hugo Wiener (1904-1993). Since my youth, I have been very interested in Jewish cabaret and its history and so I decided to write my dissertation about a relevant subject. In 2016, I began my training as a librarian at the Austrian National Library.

Now I work across a range of different fields: for many years, I have worked with the Viennese ensemble theaterfink as a dramaturg, performing on the street and using puppets to tell the audience about real crimes, which occurred in Vienna in the 19th century. As a librarian, I am involved in the “Weltmuseum Wien” project, which catalogues ethnological journals.

And finally, I work as a guide, and take great joy in telling the many interested people about Vienna's history of crime and justice at the “Wiener Kriminalmuseum”.

Unless otherwise specified, all images © Martin Burman

Author: Written by: Karin Sedlak, Translated by: Kate Garrett