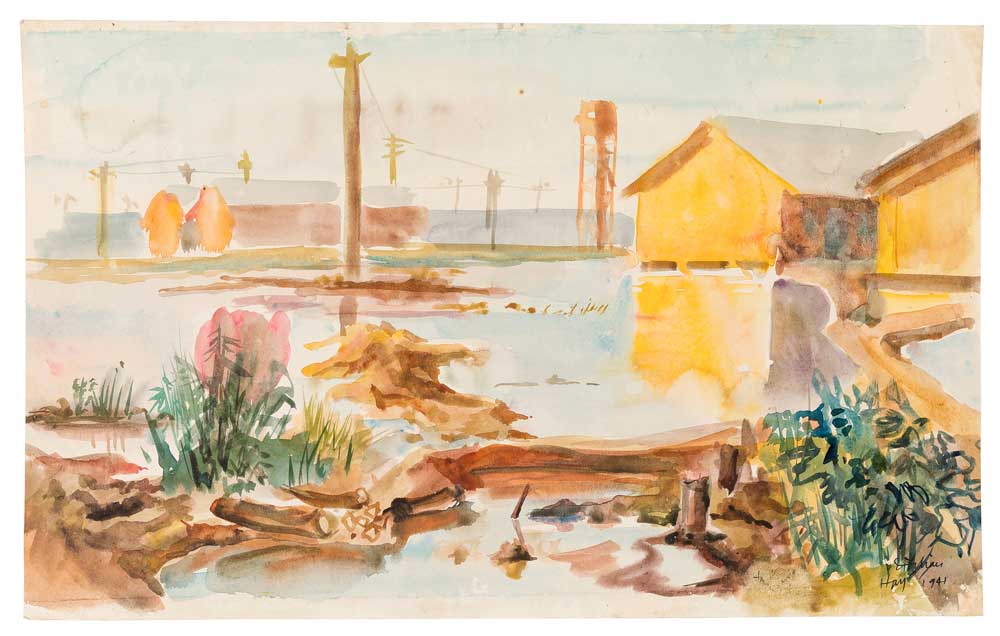

Klaus Friedeberger (1922-2019) was among the most talented, dynamic and thoughtful of Dunera artists. He was unusual among Dunera artists, and European artists generally, in seeing the mysteries and beauty of the Australian landscape. His paintings exhibited a rare sensitivity. Many of his earliest works used rich, vibrant colours, which he used carefully, picking tones and shades to depict Australian landscapes, including those he found barren and unfamiliar (see, for example, his ‘Tocumwal landscape, NSW’, c.1945).

The most talented artists – musicians, writers, painters – rarely settle on a single path; creativity and curiosity stimulate new interests and avenues of exploration. From the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s Friedeberger's paintings were figurative, focusing on the subject of children at play, and employing increasingly intense, vibrant colours. A dramatic shift took place towards the end of the 1960s: he abandoned colour, and for the next three decades worked with blacks, whites, and greys, his paintings increasingly ‘abstract’ and focused on the exploration of tones and their relationships. From the mid-1990s he began to incorporate metallic paints: silver, gold, and copper, later re-introducing vibrant, primary colours as he continued his lifelong exploration of paint and its presence on the canvas. For Friedeberger, the essence of a painting was the paint itself.

His body of work, produced over eighty years, is rich testament both to his skill and to the thought he gave his craft. The Dunera boy and art historian Franz Philipp described art as ‘one of the most serious of human activities’, an activity that ‘demands to be approached with seriousness and respect.’ Philipp saw art as a window on humanity, as the noblest of methods by which to make sense of the world. The self-effacing Friedeberger would not have claimed such a lofty achievement for himself, but his career tells us otherwise. His abstract paintings explain and enrich our lives. The art critic Andrew Lambirth wrote of his work:

Looking at painting is about the discovery of the complete nature of an image which only comes into existence through the interaction of all its constituent parts when the viewer is standing in front of it. This communication from artist to viewer through the activity of direct looking is ultimately mysterious and inexplicable. We might describe it as the aura, presence, character, even the magic of a painting, and Friedeberger’s work has it in spades. Perhaps creative art is a way of matching up the changes that take place in nature with the changes that take place within ourselves, and searching for understanding as much as reconciliation. If all art worthy of the name offers access to the centre of things, it may be said that Klaus Friedeberger’s paintings, drawings and collages throw a lasso around the centre; and in this case, the centre not only holds but reflects back an illumination that is rare in contemporary art.[1]

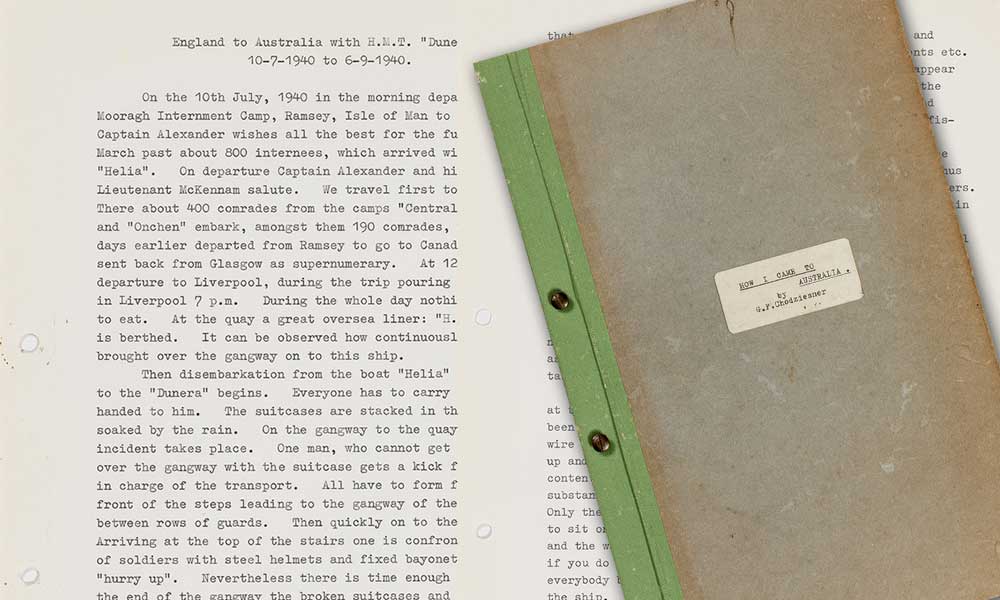

In this section, readers will find images of artworks and information about Klaus Friedeberger’s work and life. This information includes a biographical essay, an obituary printed in the Guardian newspaper (published online on 20 October 2019 and in print on 16 December 2019), and a tribute written by his wife, Julie, which was first published in the Dunera News (107, February 2020). We thank Julie for this contribution, permission to reproduce Klaus’s works on this website, and for help over several years. It is a privilege to hear stories of her husband, a remarkable man and artist.

Klaus was born in Berlin on 23 August 1922, to secular Jewish parents. Like so many Jews of his generation, he observed, “we were completely assimilated: we didn’t know we were Jews until Hitler arrived”.

His father left the family when Klaus was ten, and emigrated to Brazil. In 1937 his mother, realising that she had to get him out of Germany before he became 16, found a place for him at the Quakerschool Eerde, near Zwolle in Holland. In April 1939 he was able to emigrate to England, with the help of friends who were already there. His mother had escaped Germany a little earlier and found employment in England as a cook, but was very ill and died later that year.

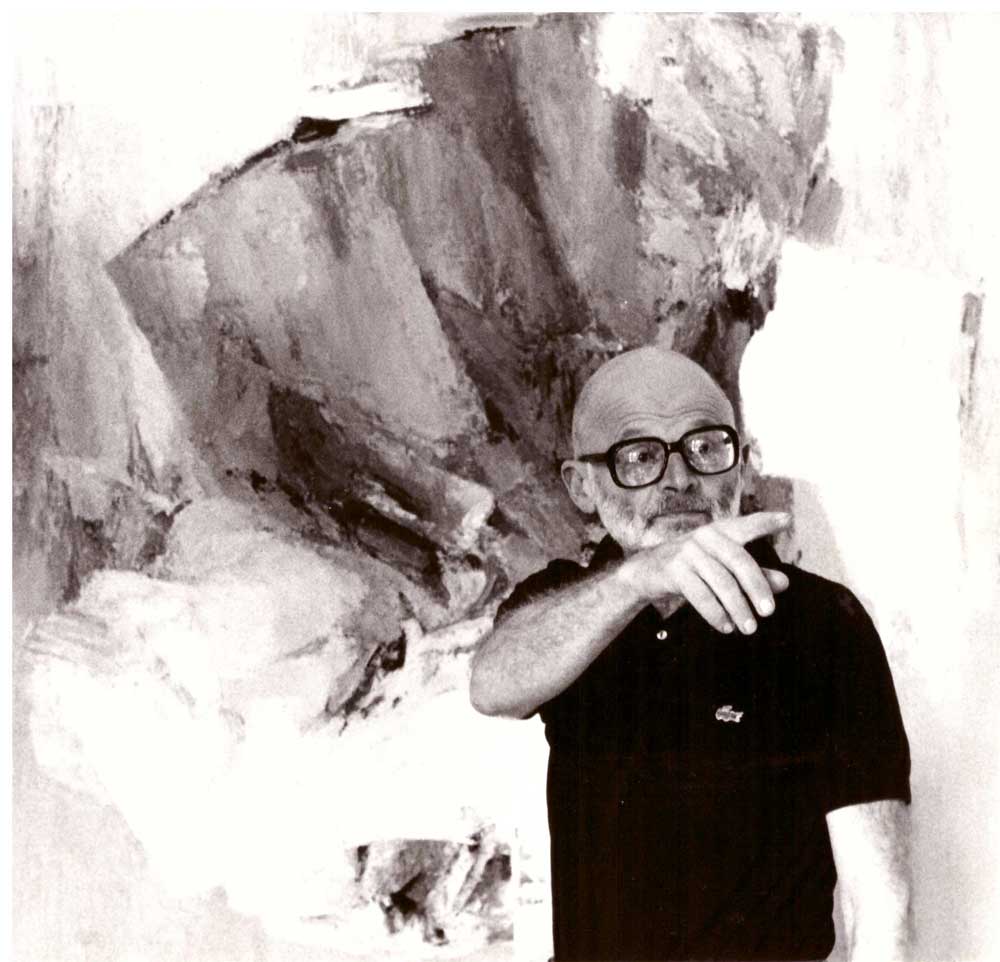

Klaus and one of his Black Space paintings.

Klaus and one of his Black Space paintings.

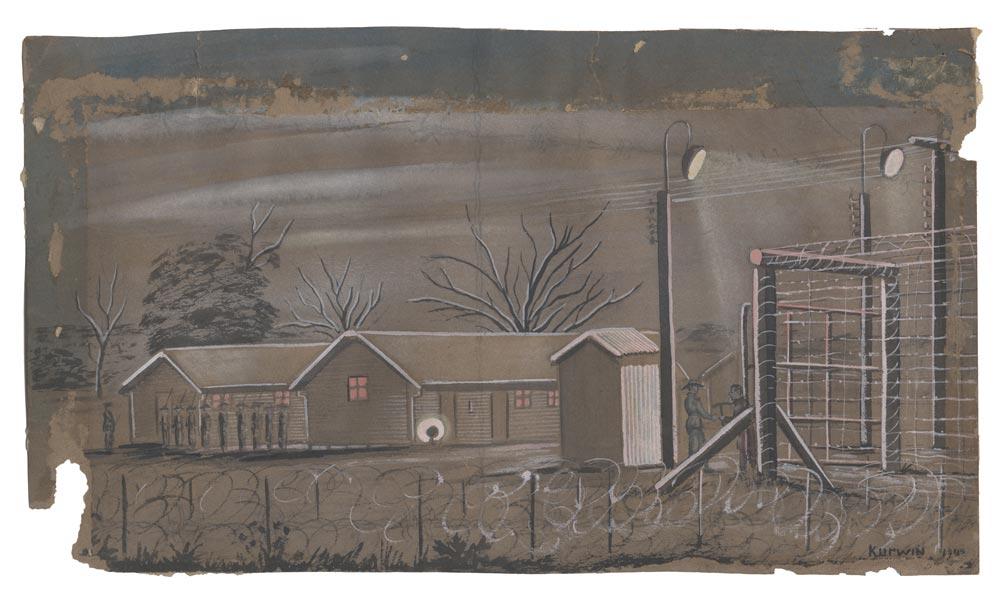

In July 1940 came the internment, and the Dunera. Klaus was one of the youngest of the internees sent from Britain to Australia: he was 17 when he was interned, and “celebrated” his 18th birthday on the voyage.

He always remembered the kindness of the Australian guards on the train to Hay, and spoke affectionately of the excellent sandwiches they were given, and the apples! – rare treats after the meagre rations dished up on the boat. He also remembered the wallabies bounding alongside the train on that long journey through a brown landscape – a surreal experience, he said; and he was always careful to point out that they were wallabies, not kangaroos. I’m not sure how he knew the difference, never having seen a kangaroo or a wallaby: perhaps the guards were the informants.

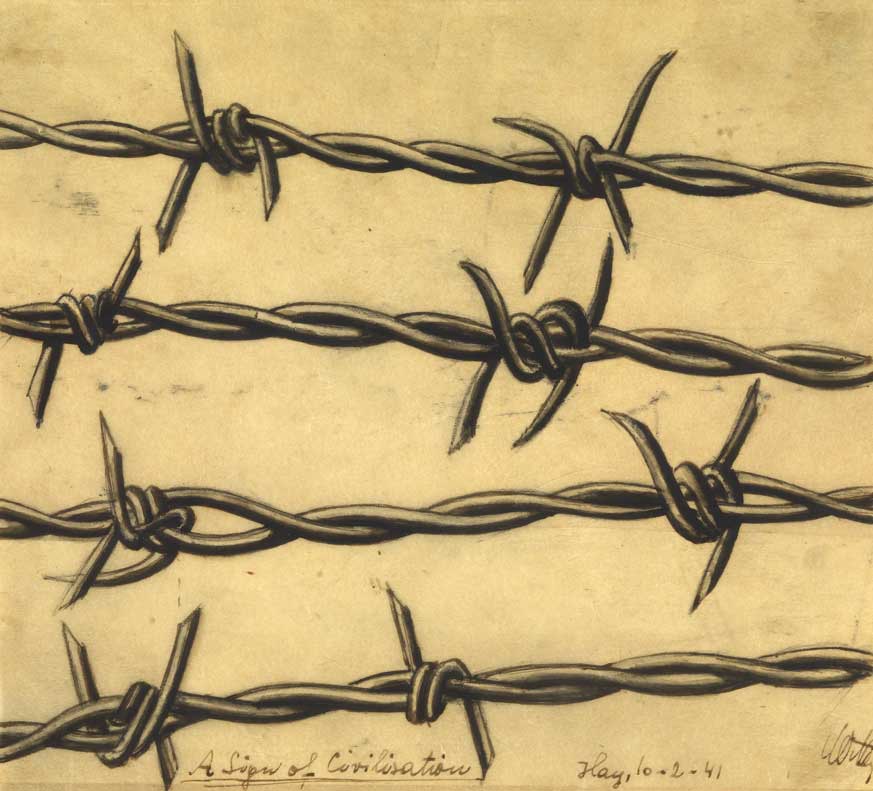

Internment proved an education for him. Although he was imprisoned behind barbed wire, there were so many brilliant, cultivated men locked up with him that it was more like an academy than a prison camp. Talking to the art critic Andrew Lambirth in 2016, he said “It was a brilliant experience in many ways. There was a camp school, choirs and quartets, and every morning those of us who painted did watercolours. I’ve got over a hundred watercolours I did in the camp.”

Anyone who had something to teach came forward and taught it. There was the sculptor Heinz Henghes, the surrealist painter and stage designer Hein Heckroth and the photographer Helmut Gernsheim; colour theory was taught by Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack from the Bauhaus, and art history by Ernst Kitzinger and Franz Philipp. And in Hay Klaus met Erwin Fabian, now aged 104 and a well-known Australian sculptor, who became a lifelong friend*.

After two and a half years of internment Klaus was released, and along with others, joined a non-combatant labour corps in the Australian army, initially to pick peaches at Kyabram, and later to transfer supplies between trains at the break of gauge. It was hard but healthy work, and he became physically very strong!

In 1946 he was demobbed and naturalised, and the following year began three years’ study of painting at East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School) under the Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme. He remembered Frank Medworth extolling “Tech” as “the best art school in the southern hemisphere”. During this time he met a number of young Australian artists, including Arthur Boyd, and Sydney Nolan, and exhibited with them at Contemporary Art Society exhibitions in Melbourne and Sydney. His fellow mature student Guy Warren became another lifelong friend. Other firm friends were the painter Tony Tuckson and the sculptor Oliffe Richmond: both died in the 1970s.

In 1950 one of his paintings won the prestigious Mosman Prize, which funded a trip back to Europe. He settled in London and continued to paint; supporting himself with freelance work as a graphic designer, and later as art director of the firm Osborne Peacock. He had intended to return to Australia, but life intervened, as it has a way of doing, and he never did.

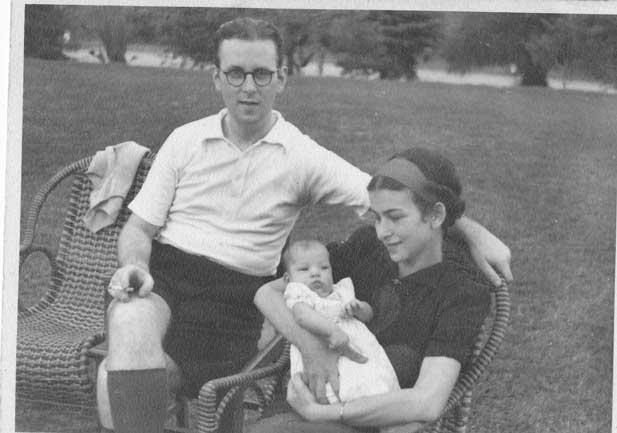

Klaus and I met on 17 September 1960, in Florence, Italy. He was on holiday; I, from New York, was on the final leg of a cycling trip around Europe. In the Brancacci Chapel of the Santa Maria della Carmine, where the splendid Masaccio frescoes are, he approached me and offered me his opera glasses so that I could see them better. This uncharacteristic act (he was quite shy) was my great good fortune. We were married two years later, and he helped me to see better for the rest of his life. Painting was his life, and it became a vitally important part of mine.

Klaus and Julie.

Klaus and Julie.

Klaus’ work was exhibited many times over the years. By the 1980s, after a long period during which he continued to practise and teach graphic design, he was able to devote himself full time to painting. In 1986 a selection of his work was shown at the Warwick Arts Trust, and in 1992 a retrospective was held at Woodlands Art Gallery. In 2007 an exhibition of his early work, which included some of those “over a hundred watercolours” done in Hay camp, was held at England & Co. Gallery in Notting Hill; and in 2010 an exhibition curated by Simon Pierse took place at the School of Art galleries in Aberystwyth.

In his essay for the catalogue of Klaus’ 2016 exhibition at the Delahunty Fine Art, London, Andrew Lambirth wrote:

Looking at painting is about the discovery of the complete nature of an image which only comes into existence through the interaction of all its constituent parts when the viewer is standing in front of it. This communication from artist to viewer through the activity of direct looking is ultimately mysterious and inexplicable. We might describe it as the aura, presence, character, even the magic of a painting, and Friedeberger’s work has it in spades. If all art worthy of the name offers access to the centre of things, it may be said that Klaus Friedeberger’s paintings, drawings and collages throw a lasso around the centre; and in this case, the centre not only holds but reflects back an illumination that is rare in contemporary art.

At about the same time, the vascular dementia from which Klaus had begun to suffer a year or so earlier, began to worsen. He was a fighter, though, and continued to climb the two flights of stairs to his studio to paint until shortly before this terrible disease finally robbed him of his ability to do so; and on 19 September 2019 he died at St Christopher’s Hospice. After a long, distressing period of increasing incapacity his death was peaceful; and it was my relief that his suffering was over. He had lived a long, fulfilling life, made glorious paintings, had lifelong friends who loved him, and was a wonderful husband and my best friend for almost 60 years.

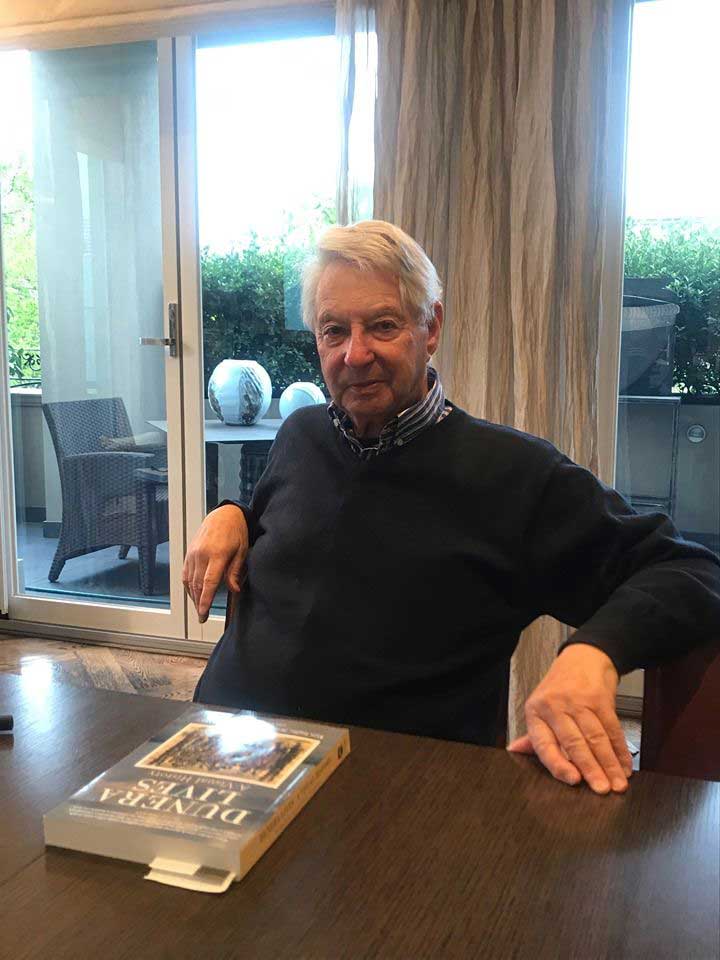

Klaus Friedeberger, 1986.

Klaus Friedeberger, 1986.

I would be happy to hear from anyone who remembers Klaus and would like to share their memories. I can be contacted This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

*Erwin Fabian died in Melbourne on 19 January 2020, aged 104.

[1] Andrew Lambirth, Introduction to Klaus Friedeberger: Paintings & Works on Paper, 1992-2015 (Delahunty exhibition catalogue), (London: Delahunty, 2015), p. 9.

All images © Ruth Wurzburger and Julie Friedeberger

Author: Introduction by Seumas Spark, Article by Julie Friedeberger