While some of the men who came to Australia on the Dunera chose later to speak about their experiences both before the war and on the ship itself – whether to the press, public, or simply to families and friends – there were many who remained silent on the subject for their entire lives. And in some instances, there were dead ends which seem as though they will remain dead ends. That's the case for Michael Kaczynski, whose father arrived on the Dunera at just 19 years old.

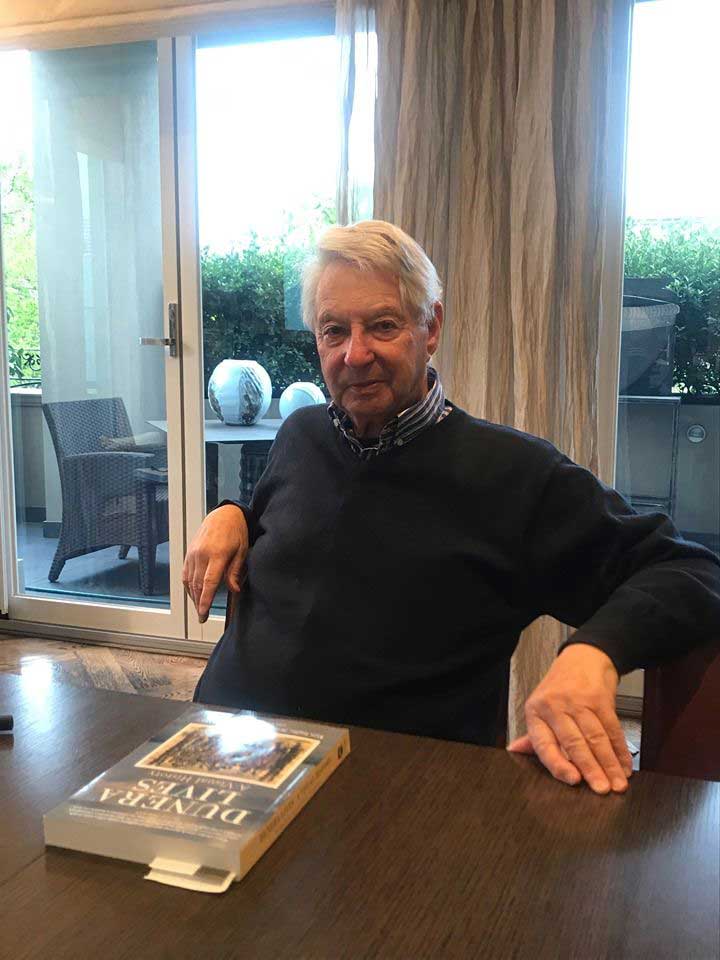

I met with Michael in his home in Melbourne's outer suburbs. It's a beautiful place, surrounded by greenery, and inside the house are a number of family heirlooms which once sat in the Berlin home of his grandfather and step grandmother, Kaethe. Michael has restored some of the furniture and values the history behind it. Unlike many Dunera children, for Michael the story of the Dunera was not ‘The Family History’ per se - certainly not in the way it is often spoken about by other descendants. The majority of what Michael knows of his father's story, and of the pre-war lives of his extended family, is the result of his own search for information.

I ask Michael about his memories of his father, Gerhard Kaczynski, and how he first became interested in his father's story. Researching his family's story, he tells me, has become something of a passion project for him.

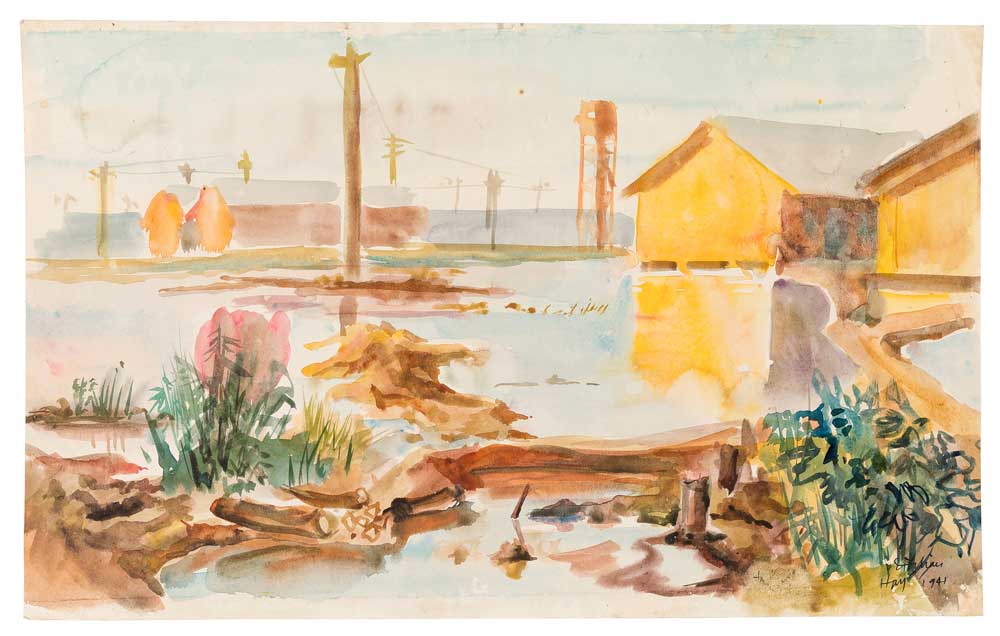

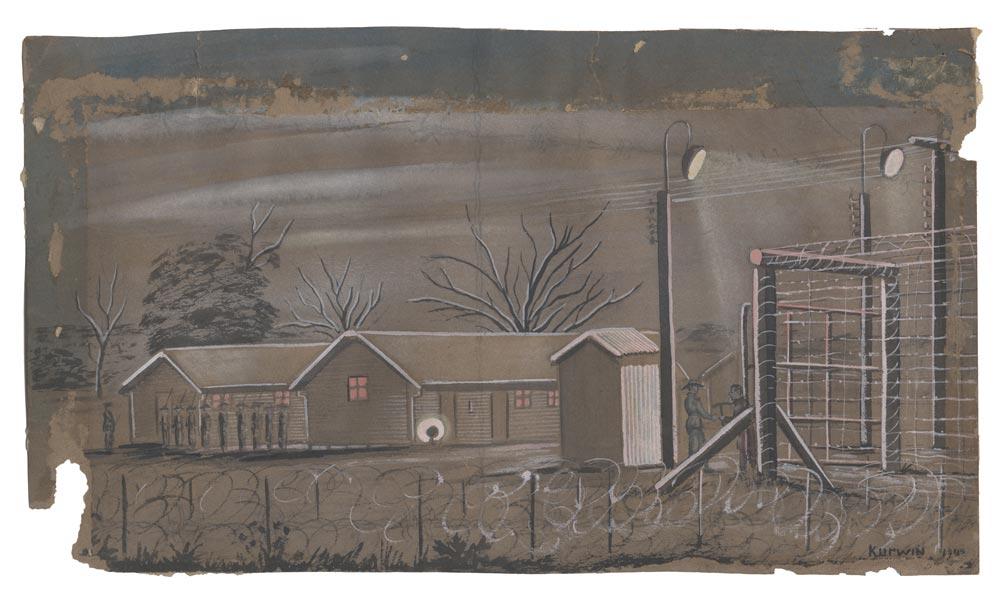

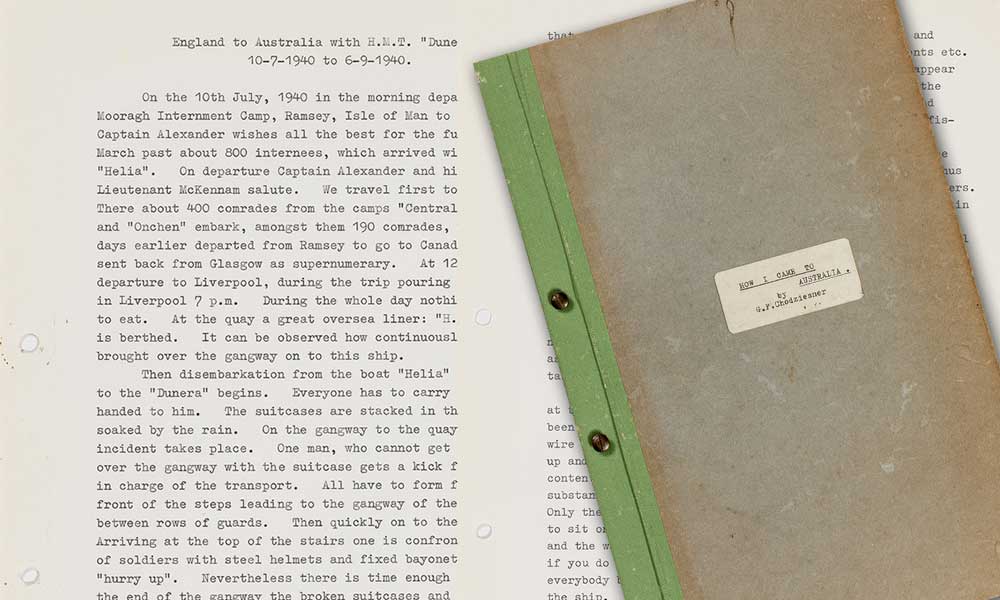

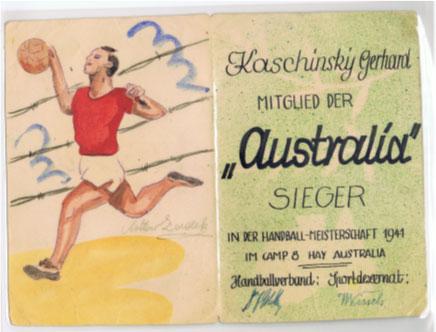

A certificate recording Jack's participation in a handball championship in Camp 8, Hay.

A certificate recording Jack's participation in a handball championship in Camp 8, Hay.

What would Michael ask his father if he had the opportunity to ask just one or two more questions? His answer becomes the theme of our conversation: ‘first of all,’ he says, ‘what happened when he left Berlin. How that happened, and then what happened to him in the UK… and about his family, how many of those he knew.’ Michael started out by putting together his family tree, continuing when he began to uncover more and more he was unsure about and names he didn't recognise. ‘There are all these uncles and aunties,’ he says, ‘people that we'd never heard of that were killed’.

Over and over in the course of his research he has come across stories like his own: of children whose parents chose not to share their past: ‘It's something that you never think to ask – it's not something that you think about [when you're younger].’ For all the answers Michael has been able to find, he's managed to uncover even more mysteries – the kind of mysteries that might have had a simple answer, if only he had asked the right question at the right time.

For example, Michael wonders about a particular couple his father became close to during his time in Britain. Michael describes them as 'lifelong friends', telling me how they used to send audio tapes back and forth to each other, and how, when he was younger, he had assumed his father must have known them for a very long time before he left. It was only later that Michael looked at the dates and realised that wasn't true: his father was in Britain for barely a year. Yet in that time, he had met this couple, and had grown so close to them that he was the best man at their wedding, keeping in touch with them for many years beyond.

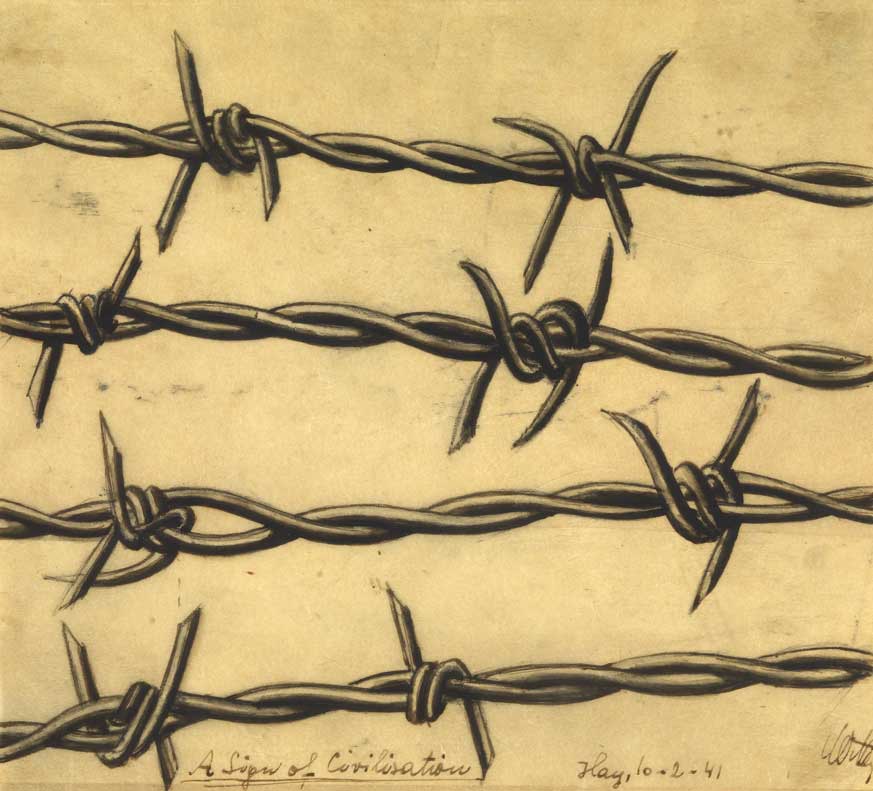

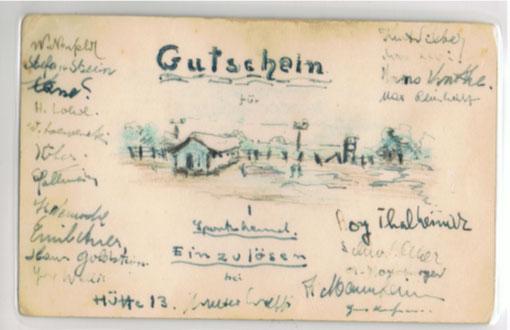

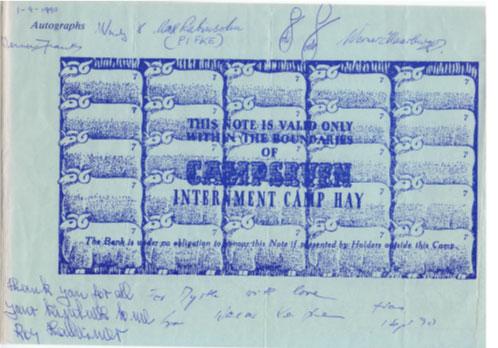

Notes bearing the signatures of some of Jack's fellow internees. The second document comes from the 1990 reunion in Hay, which was attended by many Dunera boys. Visible are the signatures of Werner Haarburger (top right) as well as Roy Thalheimer (bottom left - the son of the German Marxist activist August Thalheimer, who fled to Cuba following the German invasion of France). The bottom signature may belong to the writer Walter Kaufmann. Thalheimer's signature also appears on the first document.

Even the simple stuff seems to be missing – Michael knows his father left Germany for Britain on 20 June 1939 at the age of 18. He set sail from Bremen aboard a boat named the Columbus, information which is available in public archives. He arrived and registered in Britain on 22 June, before somehow ending up in Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire. What Michael doesn't know, however, is how or why he went to Scunthorpe, when according to letters from his mother he was expected to join relatives in Cardiff; and how he managed to board the ship in the first place: many countries had already shut their borders to refugees. Gerhard had, after all, grown up in Berlin - it is likely he was in Bremen for the sole purpose of fleeing the country.

Gerhard Kaczynski was born in the bustling metropolis of Berlin on 30 November 1920. On the Columbus's passenger manifest, his occupation is listed as 'stove fitter', but according to documentation in Michael’s keeping, his father pursued an apprenticeship with a Jewish potter after his schooling was cut short in 1935 because of his Jewish heritage. This apprenticeship ended with the Kristallnacht attacks of 10 November 1938. Otherwise Michael knows little about his father's life before his internment in Britain and deportation to Australia. Michael has spent the past few years trying to piece together this time in his father's life: from addresses on letters sent to Gerhard – later Jack – by his mother, to information taken from old notebooks and scraps of paper.

Michael tells me that when the German government began reparations payments to victims of the Holocaust in the 1950s, a letter appeared, something that indicated that his father had perhaps initially been destined for law school. Michael’s not certain how set in stone these plans were, but with a chuckle says, ‘from what I know of Dad, I can't imagine him being a lawyer.’ Jack spent most of his life working in construction and later as a greenkeeper on a golf course. Pointing to the beautiful timber furniture and decorations around us, which once sat in his grandparents' post-war Berlin home, Michael says, ‘[I imagine] life would have changed dramatically from what he thought was going to happen when he was young.’

Jack’s parents were Bernard (Benno) Kaczynski and Paula Moses. Michael’s grandmother is another mystery. In spite of the stack of letters in his possession – sent from his grandmother to her son, first in England and later during his internment in Australia – Michael knows very little about her. He does know that she remained in Germany while her son went to England and her husband to China. Whether she was unable or unwilling to leave Berlin is unclear. She remained frightened and alone in that city until 1 March 1943, when she was arrested by the Nazis. From the Yad Vashem archives Michael learned that she was murdered in Auschwitz not long after her arrest.

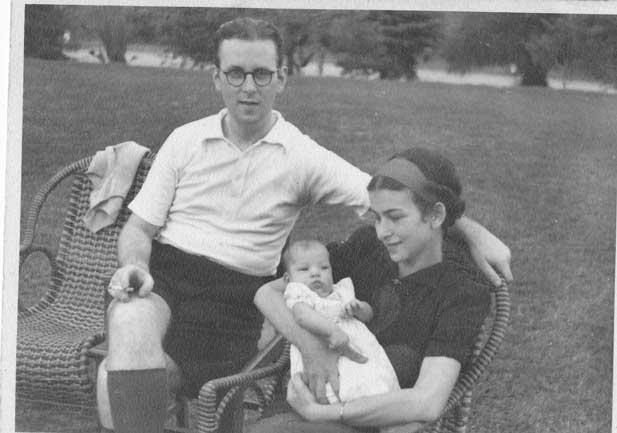

Jack with friends in East Kew. Jack is at bottom.

Jack with friends in East Kew. Jack is at bottom.

His grandfather stayed in Shanghai until the late 1940s, when he came to Australia with his second wife, Kaethe. By then Jack had married, and Michael's older siblings had been born. Michael tells me that the more he has learned about his father's history, the more he feels as if he understands him. ‘It shone a bit of a light on things that we used to think were a bit weird about Dad,’ he says. For example, he always wanted his wife to be home when he returned from work. Michael says it didn't really make sense to him at the time, but he wonders if this were due to a fear branded into him at a young age – that, at any time, someone might be taken away never to be seen again. Jack died in 1983, and as he grew older, the memories of his youth started to come back, and he became concerned with the tendency towards right-wing extremism across the world.

As we sort through the photos and documents spread out across the table, Michael draws my attention to a small booklet – a sort of enlistment notebook – and tells me of photos he found showing his grandfather wearing his uniform from his days as a soldier during the First World War. ‘Your granddad, he's just old. You don't think of him being 19 years old and being sent off to war.’

Michael's search for answers has seen him reach out to different people from all walks of life and all across the globe. Unlike many new migrants, Jack chose not to change his surname, and this connection to his family has allowed Michael to get in touch with Kaczynskis in Europe and the US. We also talk about his connection with the Dunera community. ‘Until Mum went [to the reunion in 1990],’ he says, ‘I didn't know there was a reunion’ – which isn't to say there was no connection. Michael remembers a group of men – former Dunera boys, among them taxi drivers, accountants, and salesmen – coming around to the house to play poker. They spoke in a mix of German and English – ‘I have no idea how they knew what was going on’, he tells me.

Jack (centre back) during his time in the 8th Employment Company.

Jack (centre back) during his time in the 8th Employment Company.

There's one other thing Michael would like to have been able to ask his father: what his Dunera story was. ‘Naturally there are all the stories that you read with the very bad treatment they had and the conditions on the boat – but we never heard any of that. I would like to know how he was involved or what his trip was like…. Whether that had anything to do with whether Dad didn't like being inside.’ For Michael, the story is not over. He is wary of people who say this kind of thing can never happen again: ‘it's still happening.’ In many ways, Michael feels like precious little has changed from when his father was packed on to the Dunera and shipped to Australia in 1940. He tells me how often he's spoken to people about the current refugee crises, and that he reminds them that in 1940 his father was one of those refugees. No, they say, that was different. ‘No,’ says Michael, ‘he was an enemy alien. He was the enemy of the government at the time. What's the difference?’

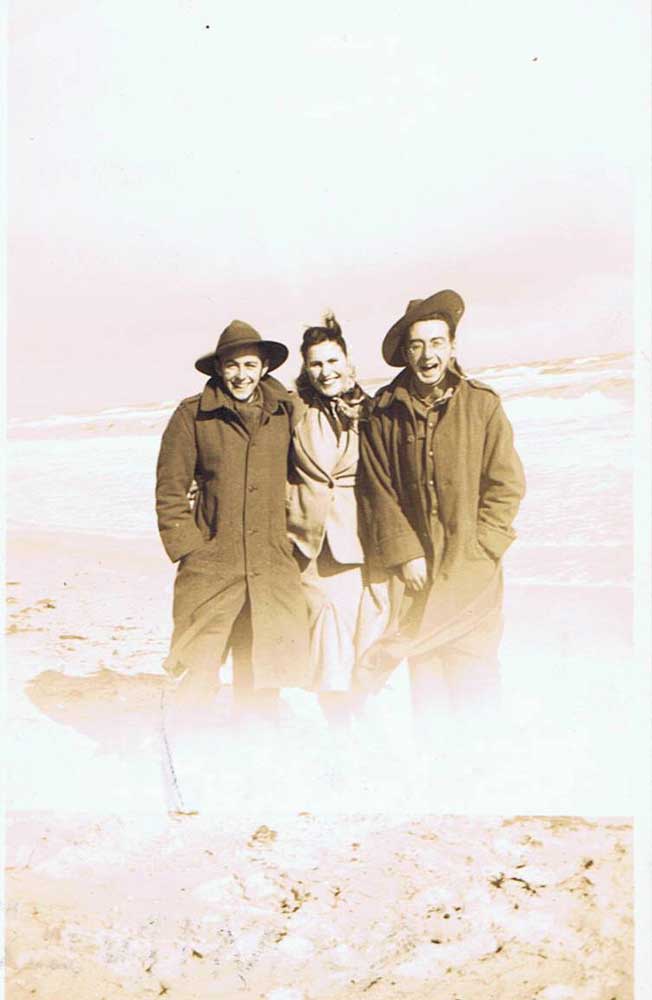

Jack (right) with friends, 1943.

Jack (right) with friends, 1943.

All images © Michael Kaczynski

Author: Kate Garrett