Kurt Hans Winkler was born in Germany on 26 February 1902, the fourth child of Protestant parents. His birthplace may have been Gransee, near Berlin, but this isn’t certain. His father, Carl Erhard Wilhelm Balduin Kurt Winkler, died about 1912, after which Kurt was sent by his mother, Emilie, to live with an aunt and uncle. Art was his passion, but he came to it slowly. He enrolled in medicine, then law, at Humboldt University in Berlin, before embarking on an art course at the Reimann School in Berlin, where Albert and Klara Reimann and their staff taught design for commercial and practical application. Reimann students were taught to meld practicality and avant-garde flair.

Flair was a Winkler characteristic. He delighted in the intoxicating world of the roaring twenties, enjoying the night life of Berlin and Paris, his vices ‘smoking, drinking and cocaine’. His attitude to sexuality was liberal (see Dunera Lives, vol. 1, pp. 229, 243-5), in keeping with the relaxed mores of the Weimar Republic, and he embraced diverse aspects of Weimar’s cultural life. In 1927 he had a role in Richard Oswald’s silent film Gehetzte Frauen. Winkler left Germany in 1933, he said because he drew unflattering cartoons of Germany’s new chancellor, Adolf Hitler. He would also have known that Nazism made no room for libertarians. He was in France for a short period, then went to Britain later that year.

In Winkler’s telling, his life before the Second World War was a heady mix of excitement and celebrity. He sketched stars of stage, screen, and sport, including Josephine Baker, Errol Flynn, Anna Pavlova, Max Schmeling and, possibly, Marlene Dietrich. How well he knew them, if at all, isn’t clear.

Winkler was viewed with suspicion by British and, later, Australian authorities. He was outspoken and flamboyant – in the words of one official, ‘an associate of undesirables and perverts’. Moreover, he was German, and Aryan at that: he had no Jewish heritage. The authorities knew that his family lived untroubled in Germany, and that his two sisters were married to German officers. On 6 November 1939 he appeared before an Enemy Alien Tribunal in London and was denied refugee status. He was classed category A, which meant he was deemed a risk to Britain, and interned at the Oratory School in Chelsea. Whether the tribunal members based their decision on security or moral concerns isn’t known, though his incarceration at this time was a sure sign of their distrust. Most men deported on the Dunera weren’t interned until the spring and summer of 1940.

Several doses of bad luck, mitigated by a piece of good fortune, followed. Winkler was deported to Canada on the ill-fated Arandora Star, but survived its sinking on 2 July 1940, when more than 800 lives were lost. He was rescued after spending many hours in the cold water of the northern Atlantic. A week after being pulled from the sea and returned to Britain, he was herded aboard the Dunera and deported to Australia. He was among the minority of Dunera internees disembarked at Port Melbourne and taken straight to Tatura.

There is no evidence that Winkler held fascist sympathies or posed any threat to Britain or Australia. On the Dunera and at Tatura he lived with Jews and other internees opposed to Hitler’s Reich, amicably as far as is known. This makes sense: his pre-war life was hardly one of fascist commitment. The Dunera boy Bern Brent remembers Winkler from Tatura: they once were paired for a dancing lesson, Bern leading and Kurt following as his ‘lady’. Still, authorities continued to regard Winkler warily, perhaps because he was inclined to oppose their prescriptions. In January 1942 he was transferred from Tatura to Loveday camp in the South Australian Riverland, where he was held with a group of other internees considered ‘doubtful’. He was returned to Tatura in May.

Possibly Winkler’s predilection for following unusual paths rankled authorities. While most Dunera internees chose freedom as soon as they could, Winkler remained interned at Tatura until 8 May 1945, the day the war ended in Europe. Why? Perhaps he had little choice. An application for release in May 1941 was refused, while authorities dealt slowly with two other petitions for freedom, in 1943 and 1944. It seems that British and Australian authorities weren’t especially attentive to his requests. But nor does he seem to have pushed his case. By the later years of the war, Australian authorities had little interest in keeping Dunera internees locked up; a forceful petition would likely have been successful. Perhaps Winkler became embittered and opted to stay at Tatura to the end of the war as a protest. Perhaps he came to fear leaving internment only to be imprisoned once more and sent back to Germany. Although unlikely, this would have been an understandable concern given his 1940 classification as a non-refugee and his treatment generally by the authorities.

On leaving Tatura, he joined the Civil Alien Corps, one of the very few Dunera internees to do so. The CAC was akin to the 8th Employment Company in that it provided manual labour, but it was a civilian body whose members did not wear the King’s uniform. The warmonger that the British and Australian authorities feared was, in fact, a pacifist. Winkler’s autobiography is dedicated to his sister Greta ‘and to the millions of people who perished through the deliberate injustices in war on all sides, making Christianity and the Geneva Convention into a mockery and a farce.’

Winkler lived in Australia until 1951, taking citizenship. He roamed Germany and Europe for the next ten years, before moving to the United States, where he settled for a time in Hawaii. He died in Berlin on 18 March 1992, having spent the last decades of his life between Europe and Australia, sketching, visiting friends and following the sun, a bon vivant to the end.

Winkler’s riotous autobiography, My Vagabond Life, was published by Regency Press in 1987. It gives information about his ‘vagabond’ life, without revealing as much as a reader might hope. The book suggests, unintentionally, that Winkler was a fantasist who put himself closer to people and events than was the case. In an interview for Fairfax’s Good Weekend magazine in 1985, Winkler described himself as a ‘star’. Sometime in the late 1980s or early 1990s Bern Brent saw Winkler in Berlin. He remembers an old man, stripped of memory, endeavouring to interest people in his autobiography.

Trying to establish the details of Winkler’s life is difficult, and will take time. Unlike Hans Rothe, for whom the archival trail is weak, there is material aplenty on Winkler scattered through various collections. Winkler believed himself to be the first artist to draw Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, daughters of King George VI. His sketch is said to have appeared on a 1938 cover of The Queen magazine, an English society publication. A search is on to find the edition. Winkler saw himself as an ‘eyewitness’ to the fateful twentieth century. More research may prove him right.

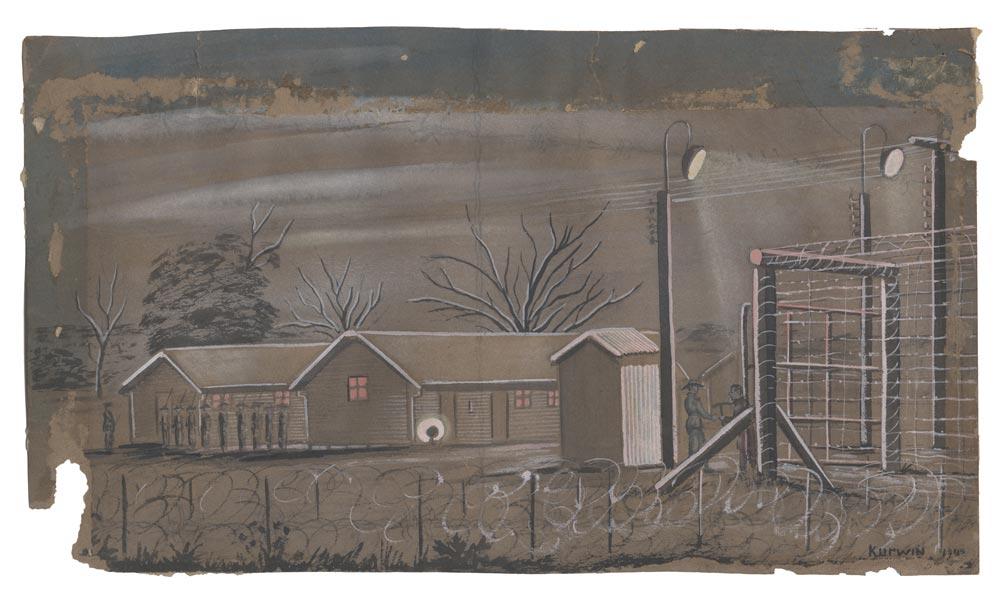

Winkler’s art, which is held by several Australian cultural institutions, has not been given due recognition. His work, almost all of it signed ‘Kurwin’, shows range and ability. He drew and painted throughout the years of his internment, leaving a vivid visual record of life behind barbed wire, 1940-45 (see Dunera Lives, vol. 1, pp. 298-302). No other Dunera artist left so complete a record of internment at Tatura. He favoured the pencil and brush, but also sculpted and carved. One of his stone carvings is with the Australian War Memorial, and at least one other is in private hands in Melbourne.

Much of Winkler’s body of work must exist beyond the public eye. The many illustrations included in My Vagabond Life confirm that he was a prolific artist out of wartime as well as in. Where are these works? A lead may have come from Regency Press, publisher of his autobiography, but it is no longer.

This article was conceived to attract responses from people who knew Kurt Winkler. We hope to illuminate the life and hidden artworks of this remarkable, resilient man. The sinking of the Arandora Star, the voyage of the Dunera, and six years internment did not diminish his optimism and enthusiasm for life. His is a remarkable story of survival and renewal.

Thanks to Bern Brent, Carol Bunyan, Gavan Daws and Andrew McNamara for information and expert advice, and to the Stocky family for permission to reproduce the Winkler artwork shown here.

Image © The Stocky family

Author: Seumas Spark