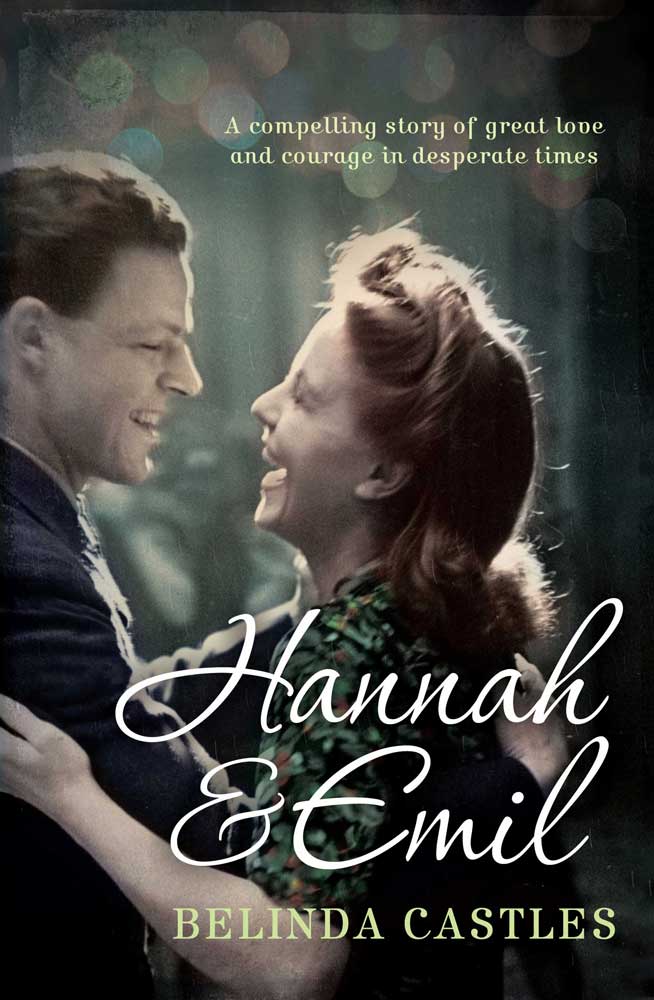

'Am I a writer because this is the sort of thing spilling from the family closet? Or just ‘fortunate’ to be the recipient of others’ painful history?' asks Belinda Castles in an article in the Southerly Journal, written to coincide with the release of her 2012 novel, Hannah and Emil. Though a work of fiction, at its core, Belinda's novel is based on her grandparents' story. The idea for the novel had begun to unfurl five years earlier, when Belinda sifted through the letters her grandmother, Fay, had written to friends in Australia. In a written interview she tells me how her grandmother's voice, ‘as I remembered it from childhood, lifted off the page’, inspired her, and made her feel as if this were a story not only that she could tell – but indeed one that she should tell.

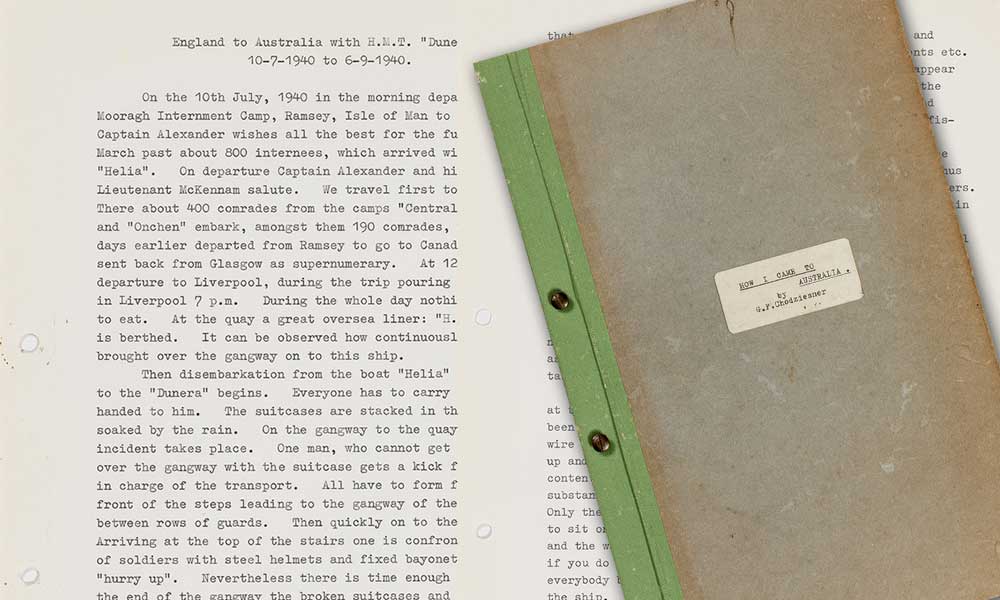

Reproduced with permission of Belinda Castles and Allen & Unwin.

Reproduced with permission of Belinda Castles and Allen & Unwin.

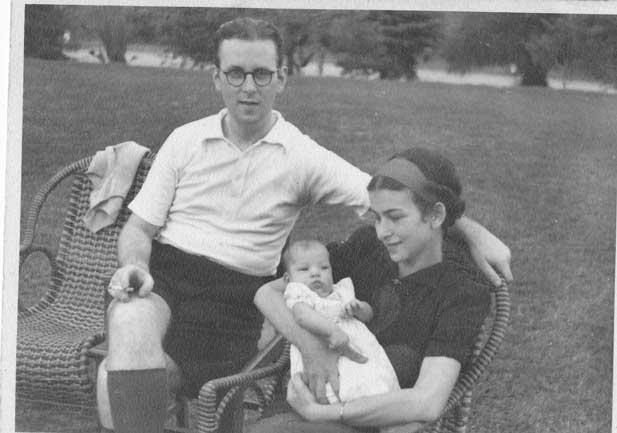

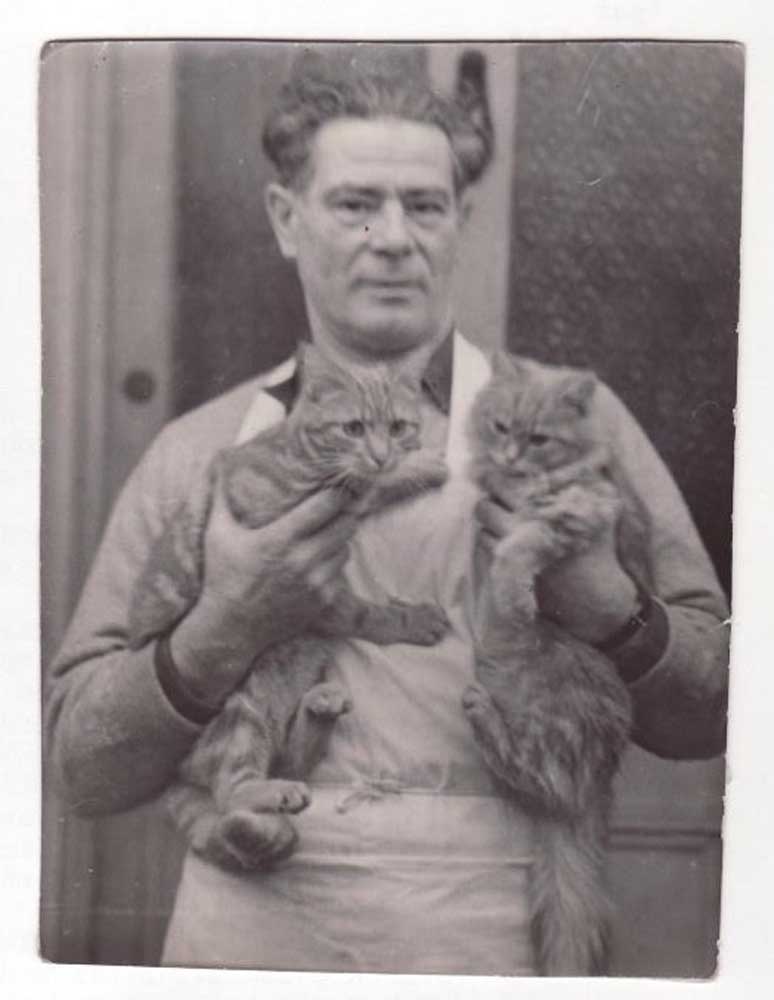

Belinda's paternal grandparents were Heinz Schloesser and Fay Jackson. Like many whose lives were torn asunder by the war, their story was anything but straightforward. Born in Dülken, Germany, in 1896, Heinz Hans Schloesser – later anglicised as Heinz Castles, ‘castles’ being the English translation of Schloesser – was the son of a prominent trade unionist and a veteran of the German army, having served on multiple fronts during the First World War.

Fay at a picnic in Australia. Heinz is seated, looking into the distance.

Fay at a picnic in Australia. Heinz is seated, looking into the distance.

Fay Jackson came from another part of the world. Born into a Jewish family in Wales, she became a member of the Labour Party and eventually found her way to Europe, where she saw a future for herself in workers' politics and the study of languages. It was in Belgium in 1933 that she met Heinz, after he was forced to flee Germany following the murder of his father.

After his appointment as German Chancellor in January 1933, one of Hitler’s first priorities was to eliminate anything considered potentially damaging to Germany's social fabric – in other words, anything that presented an obstacle to gaining total control of German life. The trade unions, of which Heinz's father was a prominent member, were immediately affected by the ruthless crackdown. Union leaders were arrested, beaten, tortured, and sent to prisons and concentration camps.

In 1934, Heinz and Fay left Belgium for Britain, where eventually they were able to find work in Winchester as youth hostel wardens. Heinz's life, Belinda tells me, comprised many different strands. Chasing those strands for Belinda took time, and in some cases turned up dead ends – or, perhaps more aptly, question marks. This uncertainty was one of Belinda's primary motivations for choosing to bring fictional elements into her novel, turning Fay and Heinz into Hannah and Emil. The story follows the main events of her grandparents’ lives, but the form of the novel left room for Belinda to fill in gaps and shed light when her extensive research – she travelled across the globe to visit her grandparents' old haunts, dug through archives, and reached out to people who had known them many years earlier – was unable to provide clarity.

Belinda Castles at the launch of Hannah and Emil (Image: Glenn Wilson).

Belinda Castles at the launch of Hannah and Emil (Image: Glenn Wilson).

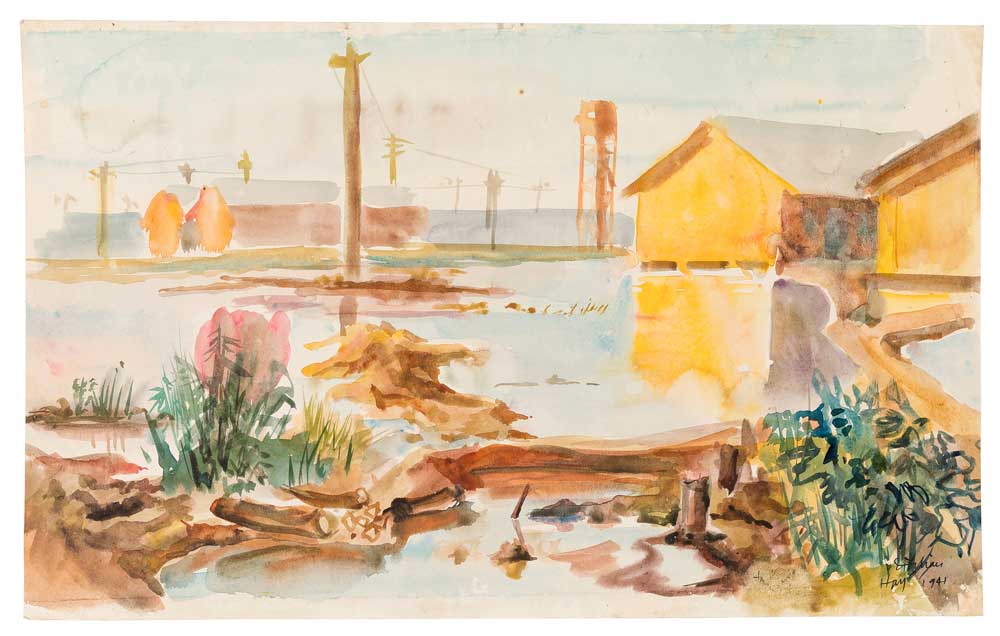

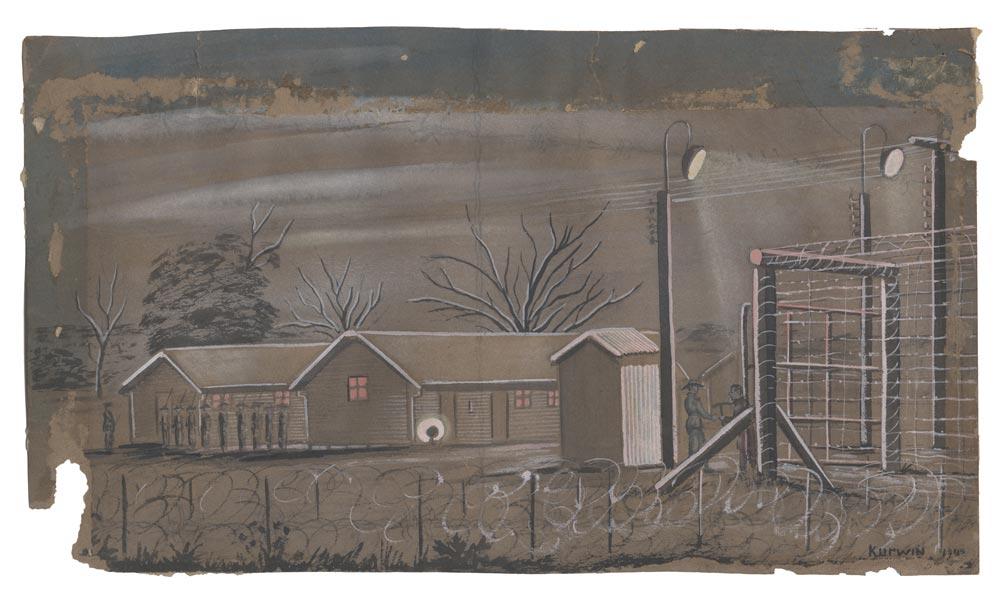

Though Heinz had lived in Britain since 1934, heightened tensions after the outbreak of the war led to his being categorised as having 'dubious loyalty'. Following his deportation to Australia on the Dunera, Fay made use of her contacts in the Labour Party and trade unions to follow him to Australia. For months, she worked tirelessly to free him from internment, engaging in ‘persistent letter campaigns…with everyone from the Prime Minister's Office down’. Eventually she was successful in securing Heinz's release; in March 1942, he left internment for war work. He and Fay married on 7 April the same year.

When I ask Belinda whether Heinz was close to other Dunera boys, she tells me she is uncertain. Born in the late 1800s, Heinz was older than many other internees, and, unlike most, not of Jewish background. In the novel she ‘invented a kind friend for him, as an imaginary gift’. Heinz, Belinda says, was a sociable man, and this friend she brought to life grew out of her hope that Heinz ‘found some comfort in the friendship of the other men’ during his internment.

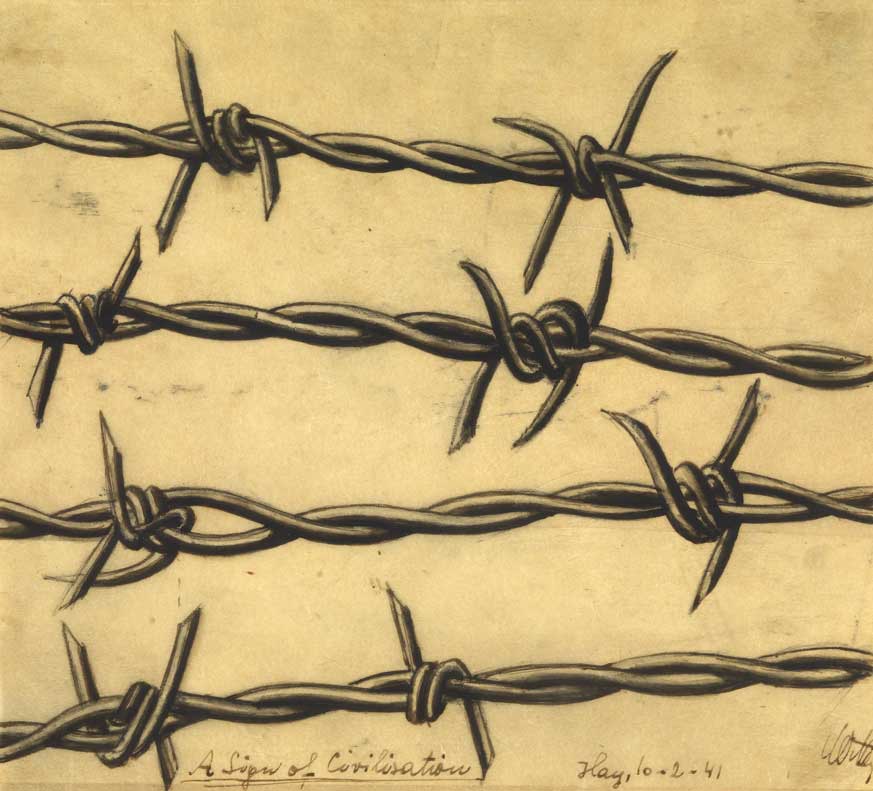

I ask Belinda for her memories. What did she think when she heard the Dunera story and learnt of this chapter of her grandparents' lives? She did not meet Heinz, but never felt as though his story, or that of her grandmother, was in any way taboo. Now living in Sydney, Belinda was born in Britain. She remembers trips to visit her grandmother in London, when her father, Frank, would tell her and her siblings their grandparents' story. And on Belinda's first trips to Australia, driving from Canberra to Adelaide, she recalls her father speaking to them of Heinz's interment in Hay, of ‘the lectures and the chess games’, and of Fay crossing oceans to find him. Having the chance to tell their story, Belinda writes, was ‘the most important piece of work I've ever done’.

Heinz and Fay chose to return to Britain with their two young sons after the war, which meant leaving behind many close friends. Fay continued to write letters to Australia for decades, and it was these letters that inspired Belinda to tell her grandparents’ story. Though Fay would at times reflect with a certain bitterness on painful memories, the letters were full of many 'affectionate detail[s] of Fay's memories of Melbourne'.

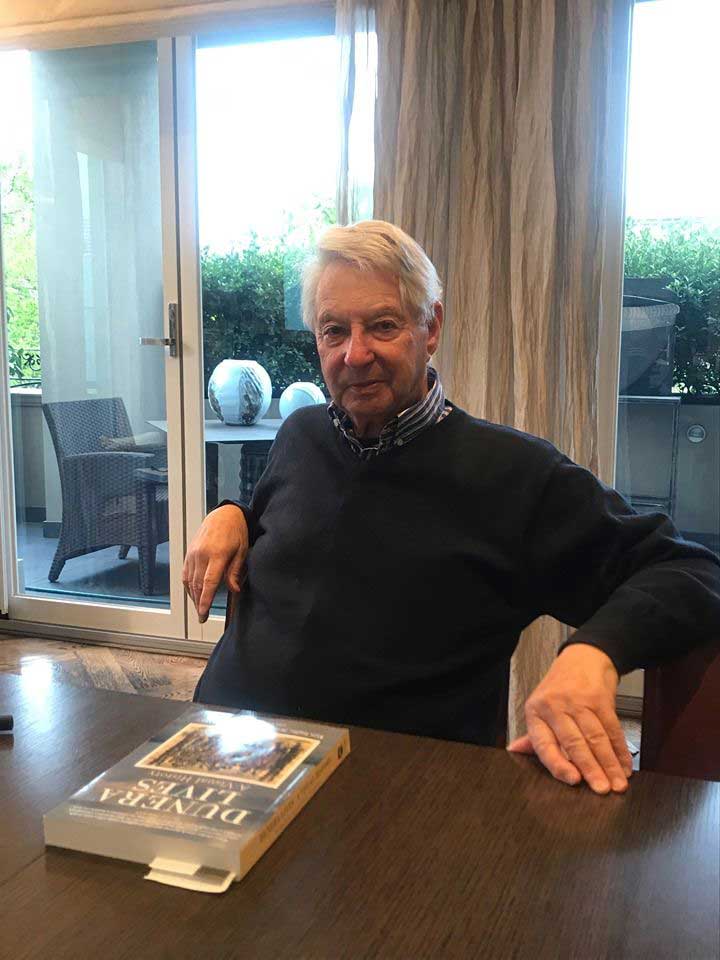

Heinz Castles.

Heinz Castles.

Fay and Heinz's two sons eventually returned to Australia, where Fay later would join them. When I ask Belinda whether her grandfather's German identity had any significant impact on her family or their customs and lives, she tells me that it was less his Germanness and more ‘his life that informed the intellectual preoccupations of his descendants’. Belinda's father, Frank, is a political scientist; her uncle, Stephen, is a sociologist who works in citizenship and migration; and Belinda's cousin works in the areas of memory studies and Germany's political history. Fay, notes Belinda, 'was quite insistent I would be a writer, and gave me plenty to work with'. Apart from Hannah and Emil, Belinda has written three other novels, including the Australian/Vogel award winning 2006 novel, The River Baptists.

Heinz Castles died in 1963, but it was not the end of his story. After his death, Fay shared with her two sons – young men by that time – that their father had been married before, and that the partnership had produced a son. Stephen and Frank had a brother. It was this story as much as any that fascinated Belinda. The story came to life in the form of a photo she found among her family's possessions. In it, Heinz sits on one side, Fay on the other. In between are Heinz's ex-wife and their son. 'What, I kept thinking, was the story of that day?', wrote Belinda in the Southerly Journal. 'I will never, ever know, so I have had to make my own'. And so, the story of Hannah and Emil was born.

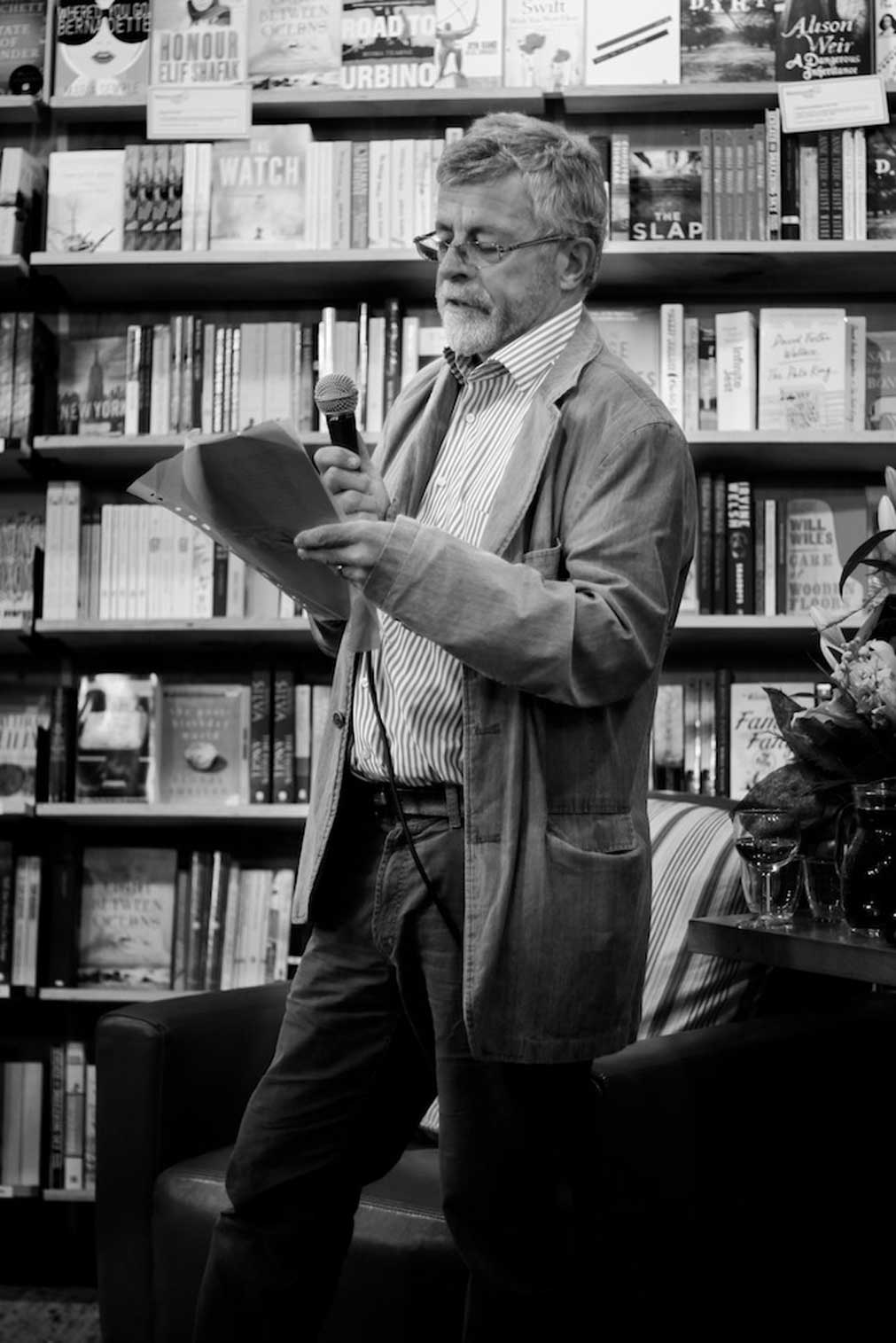

Frank Castles, Belinda's father, making a speech at the launch of Hannah and Emil (Image: Glenn Wilson).

Frank Castles, Belinda's father, making a speech at the launch of Hannah and Emil (Image: Glenn Wilson).

When Belinda began to research her grandparents' story, she says one thing that struck her was the 'extraordinary experience at its centre, friendships made between people from opposite sides of the world in the midst of chaos'. These snapshots lay bare the tragedies that rocked this period of time, and give a face to stories of persecution – a face many have not seen before. Their story, Belinda writes, 'is not the story many people think they know about German refugees'. It was the English-born Fay, not her German partner, who was Jewish – and yet it was Heinz who was forced to flee the country he had fought for, never to return.

Heinz's story, and Fay's with it, is one of suffering and courage, of loss and hope: 'these stories are precious', Belinda writes. 'It is up to the people who hold them to tell them'. I ask Belinda if she has any future plans further to explore her family's history, or whether this is where Hannah and Emil will find peace. 'I don't think so', she writes back, 'but stories can surprise you…'

Unless otherwise specified, all images © Frank Castles & Stephen Castles

Author: Kate Garrett