Heinz Henghes, sculptor, was born Gustav Heinrich Clusmann in Hamburg, Germany, on 20 August 1906. From birth he was known as Heinz, a diminutive of Heinrich; Henghes came later. His mother, Luise Winterfeldt, was Jewish, his father, August Clusmann, Lutheran, and it was in that tradition that Heinz was raised. They divorced when Heinz was 14. Luise died on Christmas day, 1927, aged 46. August was killed in July 1943, a victim of the firestorms unleashed on Hamburg by Allied bombers.

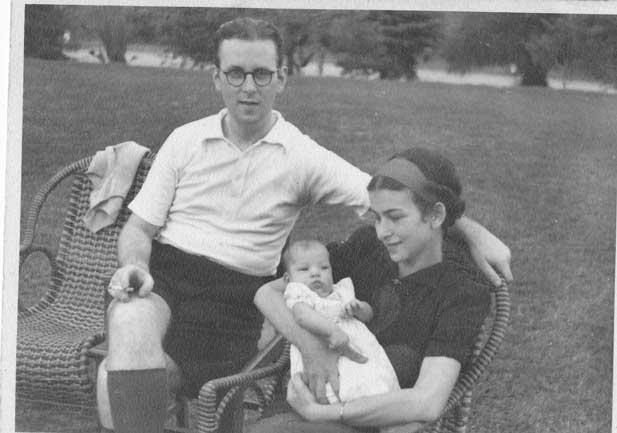

In 1924, the year he turned eighteen, Heinz left home and stowed away on a ship bound for New York; the city was his home for the next eight years. He lived there illegally, having jumped ship and avoided the formalities imposed by the American immigration system. On New Year’s Day 1931 he married Mary Elizabeth (Betty) Crabtree, an American he had met at a sculpture class. He was 24, she 19 and pregnant with his child. Peter von Clusmann was born on 27 August 1931. Heinz had adopted the ‘von’ as an affectation for American audiences – to stand out and to deflect attention from his lack of means – and in that way Peter too was ennobled. The marriage was an unhappy one, and in 1932 Heinz and Betty divorced. Heinz attempted suicide.

Later in 1932 Heinz returned to Europe. He was never to see Peter again, war and circumstance conspiring to keep them apart. Heinz went first to France, then to Rapallo on the Ligurian Sea in northern Italy where he befriended the poet Ezra Pound and Princess K. di San Faustino, wife of Prince Ranier di San Faustino, an Italian nobleman. The princess was Katherine (Kay) Sage, an American surrealist painter, and she and Heinz became close, exhibiting art together. It was Kay who suggested he adopt Henghes as his artistic moniker.

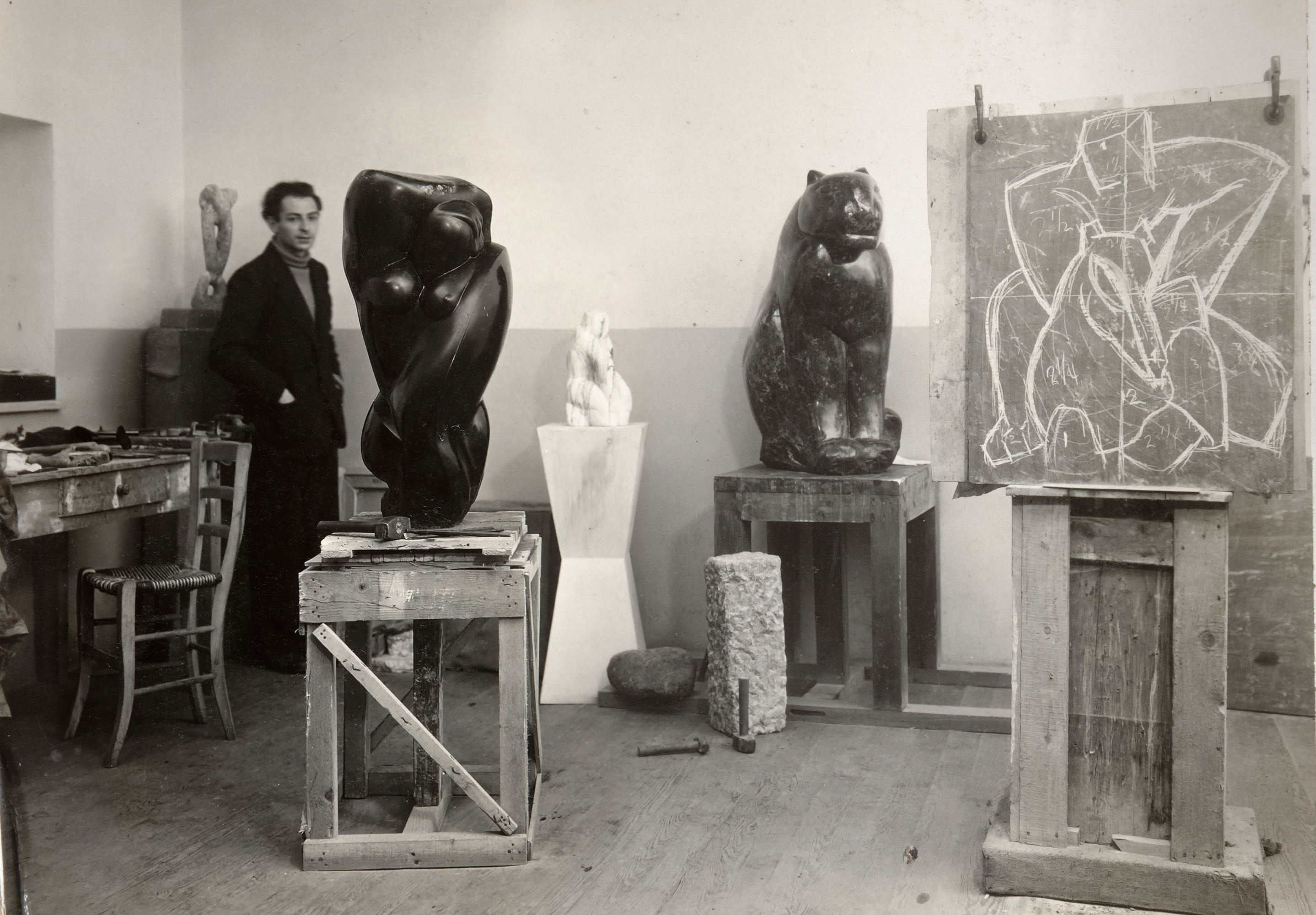

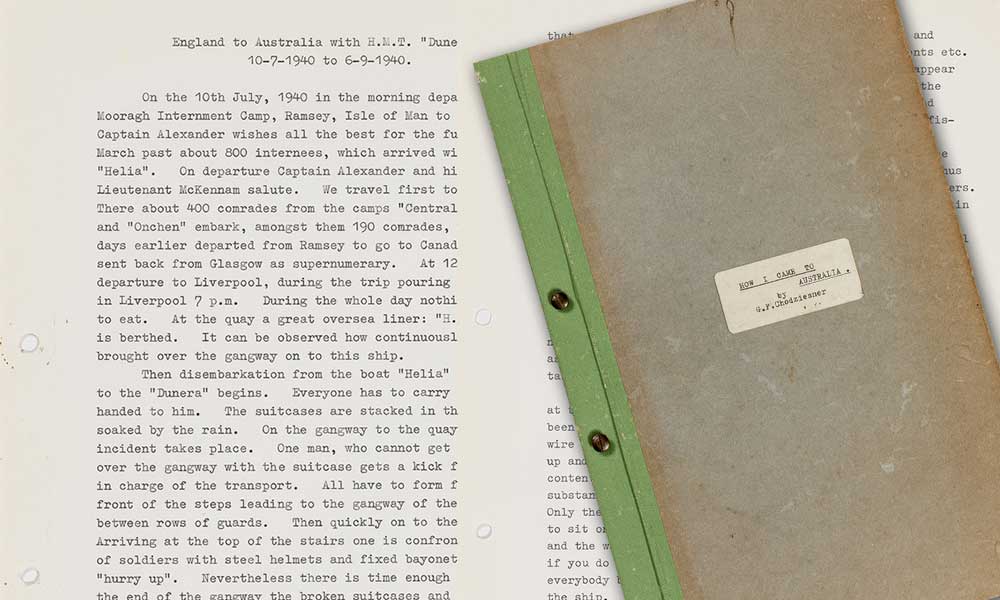

By 1937 Heinz was in London, where he took a studio and exhibited sculptures. Heinz made an application for a visa to the United States, as did many of those later deported on the Dunera, registering his interest at the American embassy in London in June 1939. And as was equally common, nothing came of his application. He remained a German national living in Britain. He was ‘captured’ on 3 July 1940 and a week later was deported to Australia on the HMT Dunera.

His internment documents, completed on arrival in Australia, offer some interesting titbits. Where other men had watches, pens or other such keepsakes in their possession, Australian authorities recorded that Heinz’s ‘personal effects’ were ‘sev[eral] paintings & sculptures’. How did these survive the journey to Australia? Listed as his next-of-kin was his ‘sister’ Katherine Tanguy of New York. Tanguy was Kay Sage, who, having divorced her prince, had started a passionate relationship with Yves Tanguy, a French surrealist artist introduced to her by Heinz in Paris before the war.

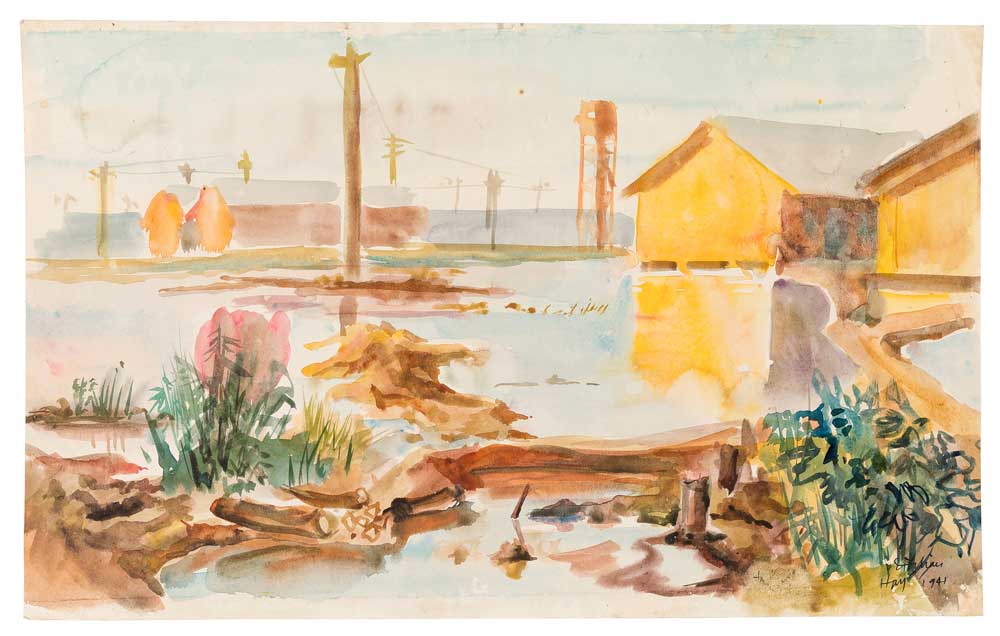

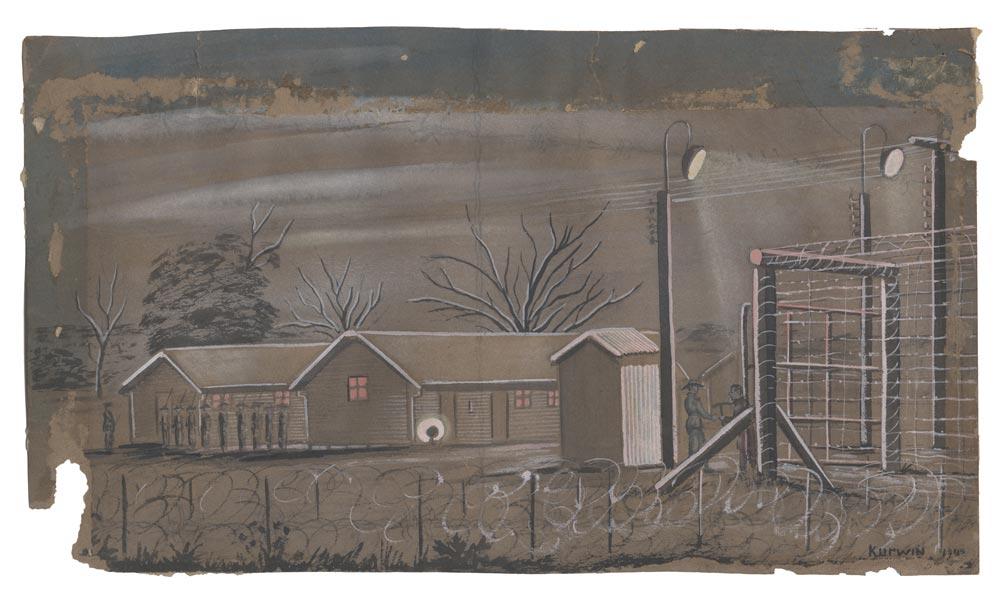

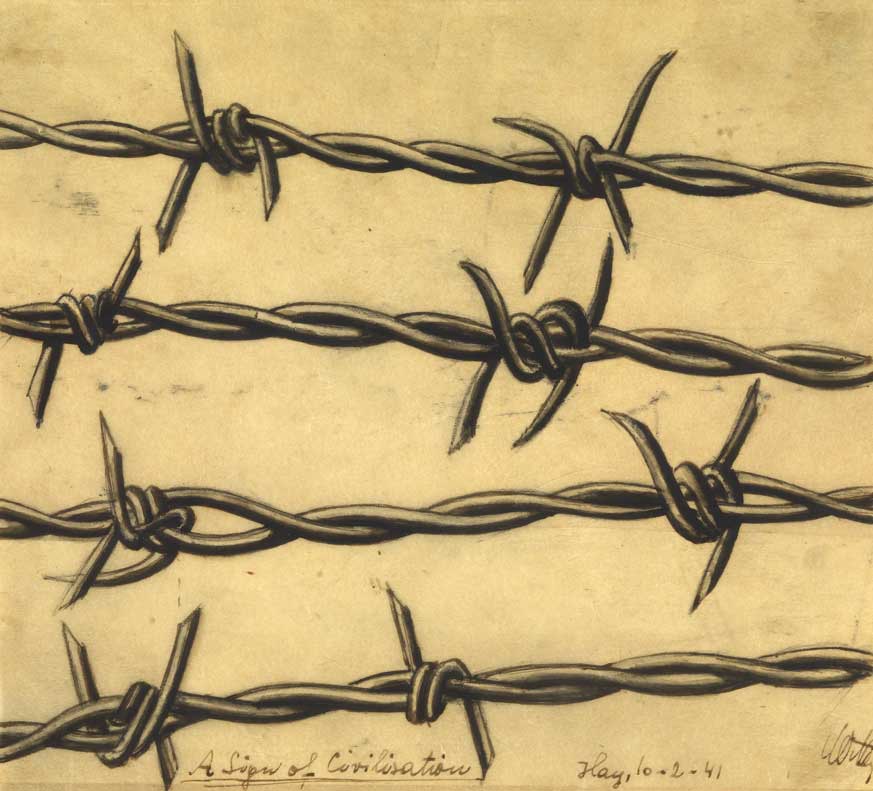

In Australia Heinz was held at Hay until 21 May 1941, where he lived in Hut 25, Camp 7. His hut mates were a diverse lot, a true representation of the many strands of the Dunera story. They were Jews, Protestants and Roman Catholics. One, Peter Froehlich, was an actor. Leo Gersten was a locksmith and plumber, Erich Gross a winemaker, and Guenter Hartwich a confectioner. Another hut mate was Heinz’s friend and fellow artist Hein Heckroth, and other artists were nearby. Erwin Fabian and George Teltscher were in Hut 26, Klaus Friedeberger in Hut 23. Heinz and Klaus had met on the Dunera. It seems that Klaus took advice from Heinz, who was older and had seen and knew more of the world.

Heinz left Hay on 21 May 1941, and on 4 June departed Australia for Britain on the TSS Themistocles. Probably the conversation was good. Among the Dunera repatriates on board were his friend Hein Heckroth, George Teltscher, the art historian Dr Ernst Kitzinger, and the author Franz Borkenau-Pollak, friend and intellectual companion of George Orwell.

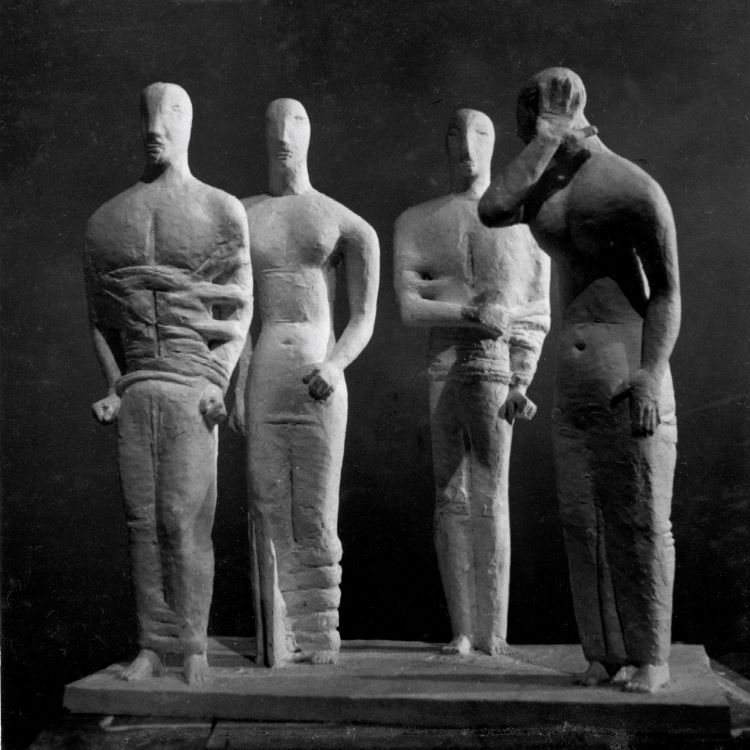

After the war Heinz continued to work as a sculptor, dividing his time between France and Britain. His pieces were daring, sometimes controversial, and always thoughtful. He exhibited widely, in Britain and Europe, and as with so many Dunera artists, combined shows and practice with pedagogy. His students were many, including those whom he encouraged at the Winchester School of Art where he taught from 1964-73.

In 1948 he married Daphne Gow, a ballet dancer. Four years thereafter he changed his name formally, becoming Henry Henghes (Henri when in France). Later, he would work again under the name Heinz, and that name was preferred by those closest to him. He died in Bordeaux on 20 December 1975, aged 69.

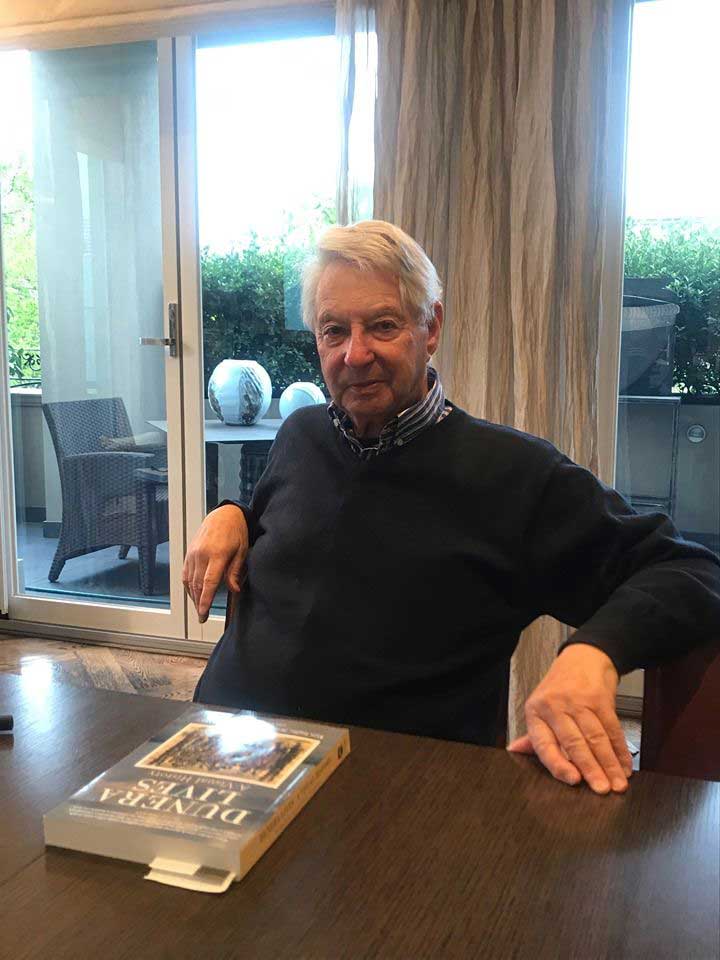

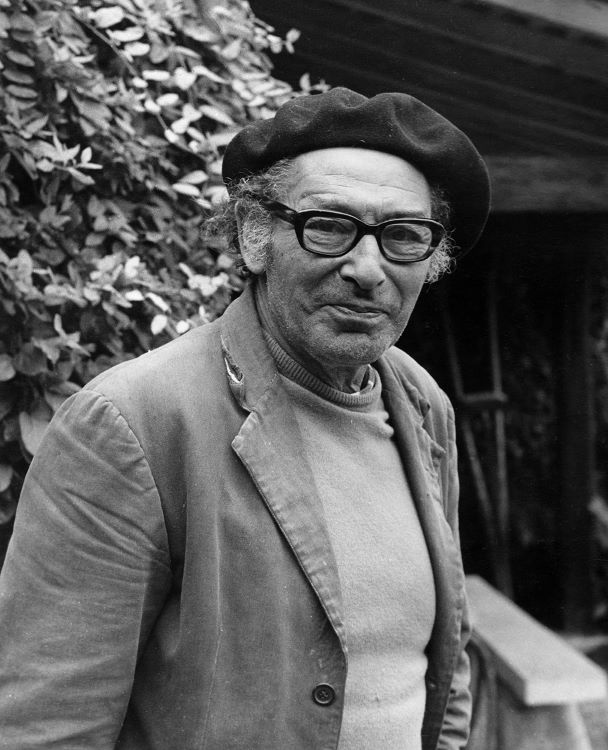

Heinz Henghes in France in 1973.

Heinz Henghes in France in 1973.

Ian Henghes was born to Heinz and Daphne in France in 1959. Much of what we know about Heinz and his life comes from Ian, now the custodian of his father’s works and legacy. Ian maintains a website, offered in both English and French, where readers learn about Heinz and his remarkable life as a stowaway, artist, refugee and teacher. The website includes vivid photographs of many of Heinz’s works.

In recent times Ian has been writing about his father with a view to producing a book-length biography. We are delighted to share some of Ian’s account of his father’s internment and time in Australia.

Thanks to Ian Henghes for his help with this introduction, and for permission to reproduce the following text.

https://share.diditon.com/xQuzppDX

All images © Ian Henghes

Author: Introduction by Seumas Spark, Linked Article by Ian Henghes