Robert Hofmann, born in Vienna on 7 August 1889, is a particularly interesting Dunera boy. Unlike many who came to Australia as teenagers or young adults, Robert boarded the Dunera at age 51 with a life and career in Europe behind him. And, unlike many other older Dunera men, he never sought to return to his life in Europe. An accomplished artist, he spent the next four and a half decades abroad: in Australia, and later the United States, where he died in Syracuse, New York, in 1987 at the age of 97. With the help of his former colleague, student, and friend, New York-based artist Mark Topp; Robert’s niece, the retired professor and writer Greta Hofmann Nemiroff; and Dunera researchers Elisabeth Lebensaft and Christoph Mentschl, we have been able to gain valuable insight into Robert Hofmann's life and artistic career across three continents.

Robert was one of nine children born to Edmund Hofmann and Henriette, née Hock, both of whom were Jewish. Greta, the daughter of Robert's youngest brother Ernest, writes that while Robert's sister Martha was a staunch Zionist, as far as she is aware the Hofmanns were largely assimilated and not religious. Her own father was an atheist who never practised any religion.

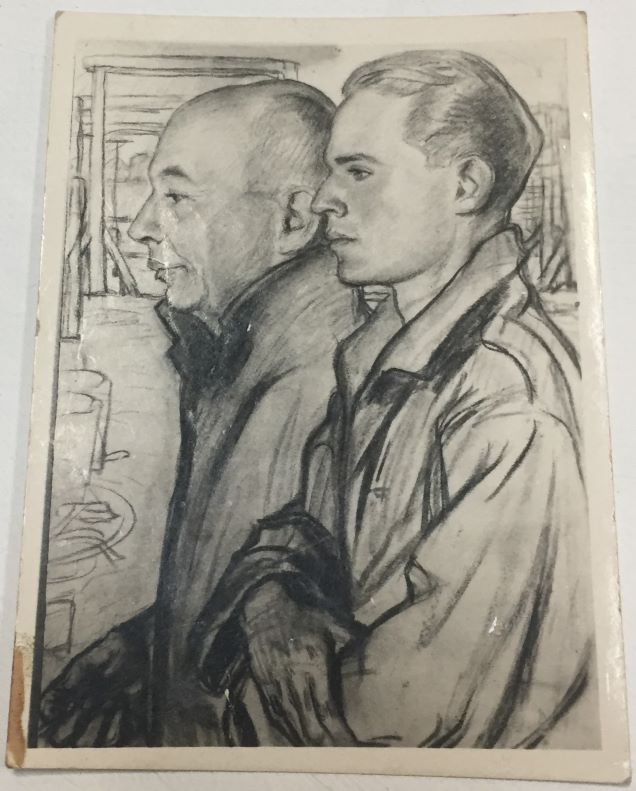

Robert (left) and his brother.

Robert (left) and his brother.

Robert's father Edmund was born on 10 July 1849 in Alsö-Lendva – now part of Hungary – and died in Vienna when Robert was in his early 20s, on 27 February 1923 . He worked in the timber trade and was the founder and publisher of the journal Continentale Holz-Zeitung (Continental Wood Journal) in Vienna. According to one of his daughters, he was also an honorary professor at the Hochschule für Bodenkultur, the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna.

After graduating from high school and completing his voluntary service year, Robert studied painting under Josef Jungwirth in Vienna at the Akademie der bildenden Künste, the Academy of Fine Arts, from winter 1910 to summer 1914. He often spent his holidays studying abroad, in France and Belgium, and was able to finance additional travel to Italy, Greece and Egypt through prizes and scholarships.

The outbreak of the First World War resulted in a long disruption to Robert's studies. Mobilisation meant that by 2 August 1914 he was enlisted. He served in the military for the entirety of the war, reaching the rank of lieutenant. Robert was originally deployed in Galicia. He distinguished himself during the Battle of Komarow and received several awards for his commitment. These years in the military left an indelible mark – and it was not just the imagery, which he would continue to incorporate into his work for years to come. Though they met many decades after Robert's time in the military, Mark Topp remembers that ‘Robert considered himself a soldier first’: ‘To have survived the First World War when so many perished was not lost on him. He came close to death once or twice’.

Robert in Gaza, summer 1917.

Robert in Gaza, summer 1917.

Robert continued to pursue art during his military service, drawing scenes of war in Galicia, and later in the Middle East and he participated in multiple exhibitions. Some of his works were published in the Leipziger Illustrierte Zeitung (Leipzig Illustrated Newspaper), including a portrait of the Austrian Corps Commander General Krobatin – one of many officers’ portraits he painted. According to Mark, it was this success that convinced Robert's father that his son might have a future as an artist.

From August 1917, Robert was deployed in battles in the Middle East, Turkey, Gaza, Jerusalem and the West Bank. In autumn 1918, he was a liaison officer with the Ottoman Imperial Army Command, and proved himself during the collapse of the Palestinian front in September 1918. The description of his service repeatedly emphasises his cold-blooded courage.

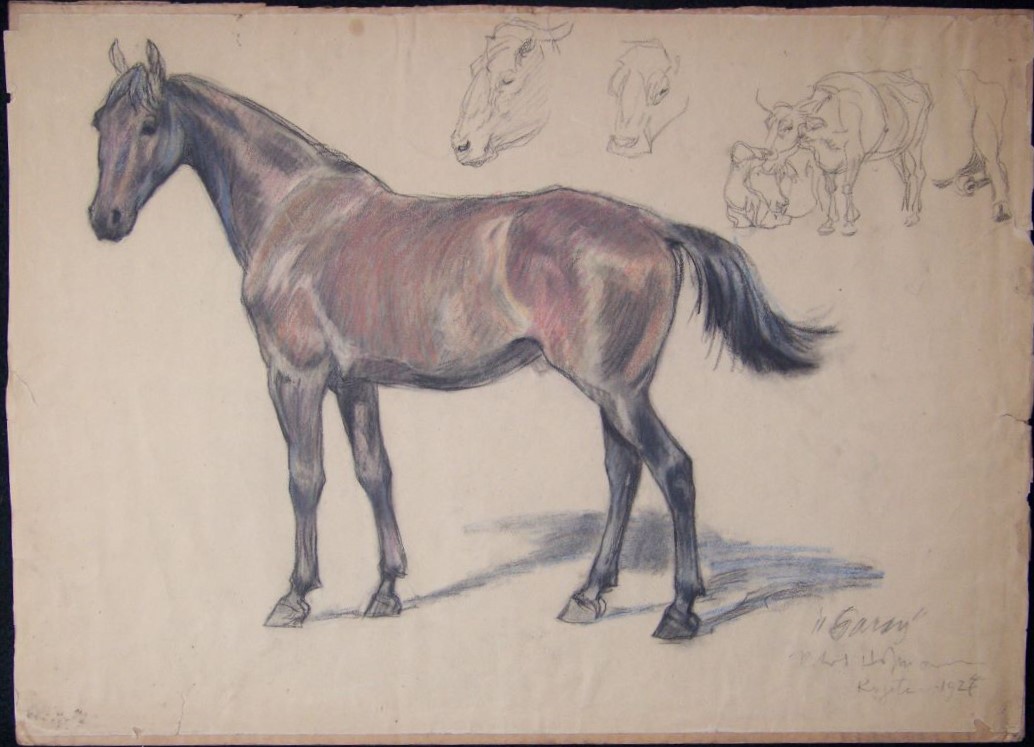

Horses were a favourite subject of Hofmann's. This drawing was completed in Egypt in 1927.

Horses were a favourite subject of Hofmann's. This drawing was completed in Egypt in 1927.

After the war, Robert continued his education at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna, where he studied under Professor Kasimir Pochwalski from winter 1918 to summer 1919, then with Professor Jungwirth from 1919-22. After completing his studies, Robert became a portrait painter, often working for aristocrats and industrialists., Even early in his career, his talents were recognised: in 1922, he won the Prix de Rome, a prestigious award comparable to the Nobel Prize for the art world. He maintained a studio in Prague for a time. When the Nazis came to power, Robert made one final trip to Vienna: an attempt to help his mother and sisters escape.

The trip was made against the recommendations of Robert’s friends, who warned he would be killed if he returned. Nonetheless, he boarded a bus to the city of his birth, wearing his military uniform and medals. ‘He kept that bus ticket stub for the rest of his life,’ Mark writes. He called it ‘his badge of honour’. During his time in Vienna, Robert was interrogated by the Gestapo.

The majority of the Hofmann children managed to escape from Austria as the Nazi Party grew in Germany: they fled to England, Palestine and beyond. Robert's sister Hedwig made for the US, where many years later she and Robert would be reunited. Greta's father Ernest had emigrated to Canada with his wife Lisl in 1930 for better work opportunities. Greta writes that ‘he was deeply concerned with and involved in trying to save his family from the Nazis after the Anschluss, if not before’. Unfortunately, the anti-Semitic climate in Canada at the time made this impossible: the country accepted only around 5000 Jewish refugees from Europe, a fraction of the number taken in by other democracies at the time. Robert's mother Henriette refused to leave her city of birth and is believed to have died of starvation on 21 January 1941. His eldest sister Ada was deported to Belarus in 1943, where she was murdered on arrival. Robert left Vienna for Britain in March 1939. He would not return to Austria: as Mark writes, ‘Robert never returned to Vienna… he was concerned that at any time, he might be sitting next to the person who starved his mother to death’.

Little is known about Robert's life in the years between his departure from Vienna and his arrival in New York state. Like his sister Kaethe, he escaped to Britain as a refugee, where he worked in Harrods for a time, painting portraits. Mark was able to shed some light on how this connection came to be: Robert had completed a portrait of a Jesuit priest, who took the piece to Harrods to be framed. Staff members were so impressed that Robert was offered ‘a studio and a position as portrait artist in residence’.

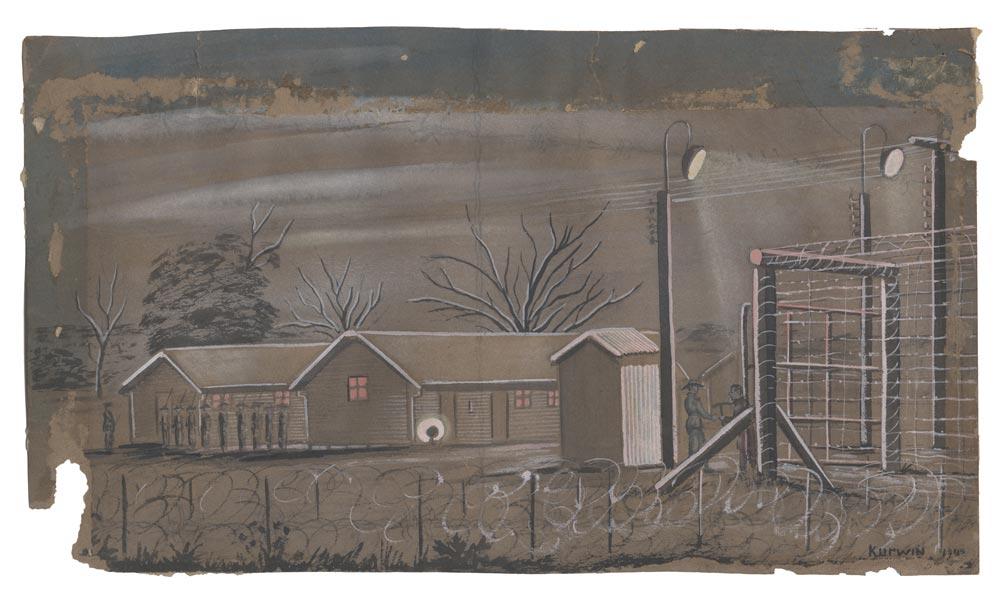

A photograph of a sketch completed in Tatura in 1942. Writing on the back reads: 'Internment camp (what a bad joke)'.

A photograph of a sketch completed in Tatura in 1942. Writing on the back reads: 'Internment camp (what a bad joke)'.

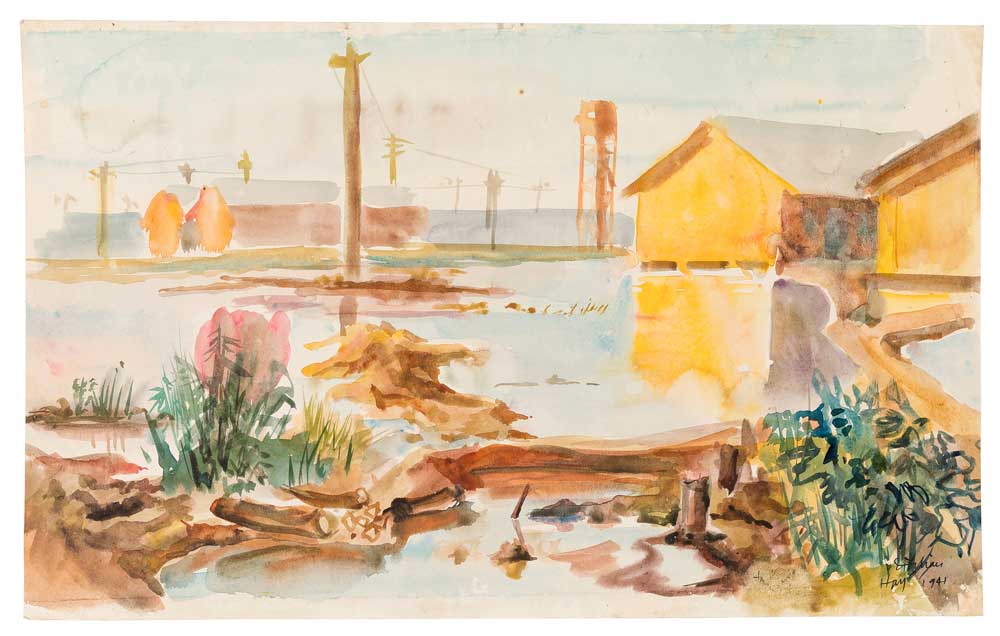

In 1940 he was deported to Australia alongside the other Dunera internees and was incarcerated at Hay, then Orange, and finally Tatura. Robert became naturalised in 1946, and lived in Australia until he moved to Syracuse, New York, in 1956, where his sister Dr Hedwig Fischer had been living since fleeing Nazi Europe. She was by that time a well-known dermatologist in the Syracuse area and, as president of the French club there, had connected with other refugees in the region.

With his sister's assistance Robert was able to settle into his life in Syracuse and build a network of connections, establishing himself as an artist. Hedwig and Robert remained close for the rest of their lives and lived together for many years in the house that doubled as Hedwig's office and clinic, located not far from Robert's Syracuse studio.

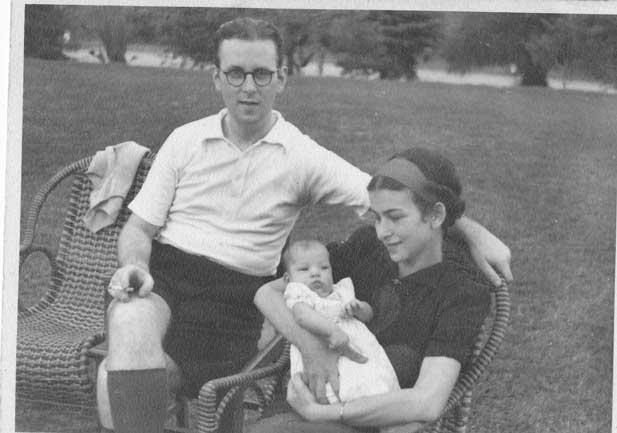

It was during his early years in the United States that Robert met his brother's daughter, Greta, and the students Mark Topp and James Skvarch, to whom he would later grow close. Greta met Robert when he visited Canada and the United States from Australia in the late 1940s. Just eight at the time, she remembers him as a ‘stocky man with ruddy skin, very white thick hair and brilliant blue eyes. Handsome and a good raconteur’. Robert later visited his brother's family in Montreal, and Greta has a fond memory of Robert sitting down with her to draw some of Australia's peculiar animals. She recently found this piece of paper among a collection of family mementoes; and on her wall hangs a pastel portrait he drew of her at that time. ‘As for Robert's career as an artist,’ Greta writes, ‘I know very little about it. I think he lived mainly on commissions’. Mark, who met Robert several years after he had established himself in New York, shared some of his memories of Robert's life there.

Mark met Robert in the late 1960s when, as a high school student, he began studying portraiture under his direction. He'd heard about the classes through a friend of the family: ‘at the time, I had no idea of [Robert's] life experiences and enjoyed the classes and paid attention’. It was not until about five years later, when they ran into each other walking down a Syracuse street that their friendship formed.

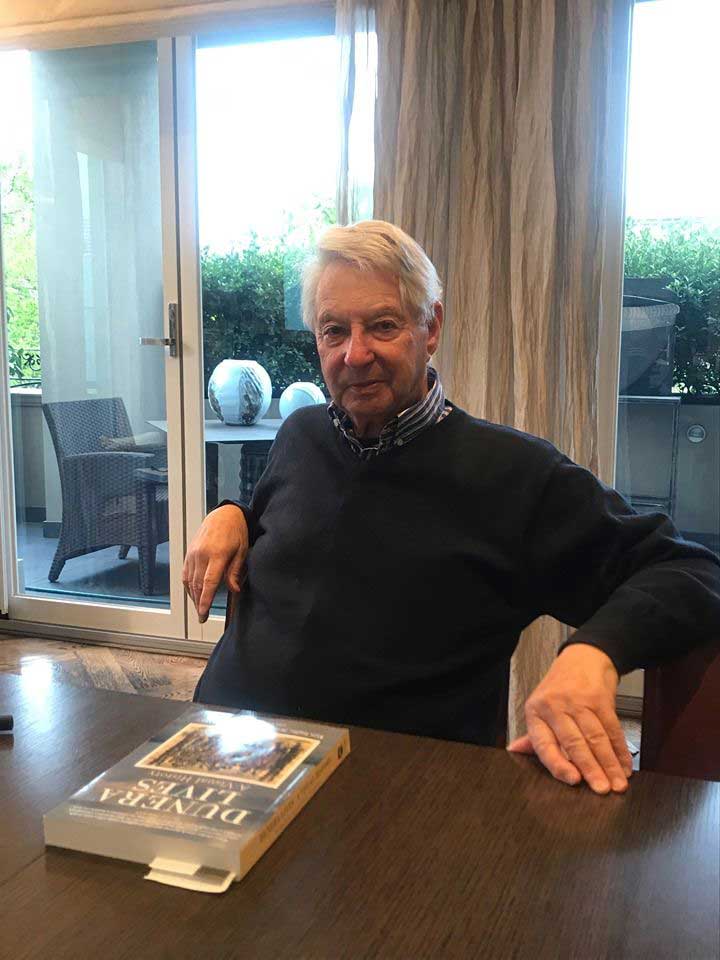

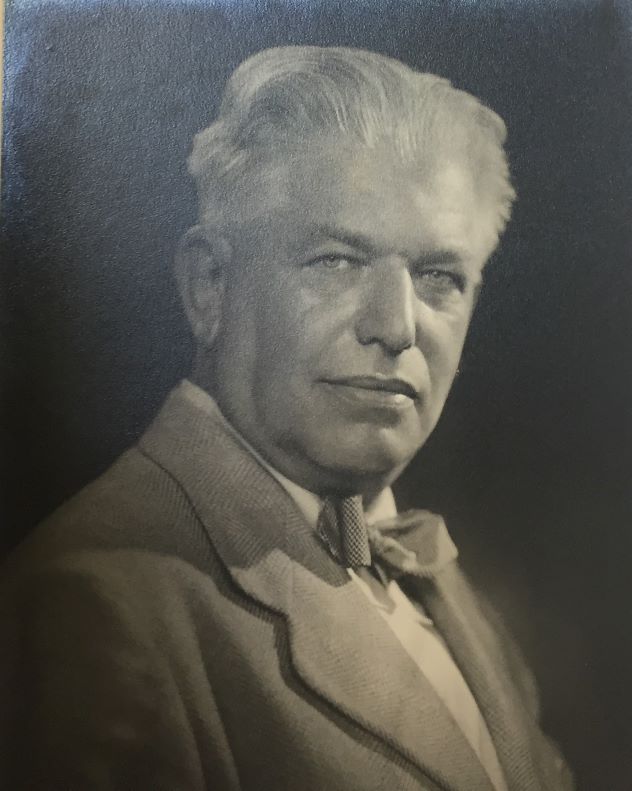

Robert, later in life.

Robert, later in life.

Mark has many fond memories of his years of friendship with Robert. Mark was instrumental in introducing Robert to Mr Coy Ludwig, the Director of The Tyler Gallery of Fine Arts at Oswego University, who helped them to mount a travelling two-year exhibition through the State University of New York. It ran from 1979 to 1980, and was titled ‘Robert Hofmann, Artist Soldier in the Middle East’. Mark would help to host this exhibition again many years later, in 2014, at Le Moyne College.

‘[Robert's] studio,’ according to Mark, ‘was often a gathering place for students and friends’. He remembers with particular fondness ‘The Tales of Hofmann’ – Robert's phrase – where he would regale students with stories of his life as they pored over his work. ‘We never tired of hearing "The Tales of Hofmann"’, writes Mark. ‘I can't say I remember them all’, though he notes that he does not recall much mention of Australia beyond an anecdote here or there. Robert’s experiences there were simply another facet of an already complex life. Robert was also not one to shy from political discourse, and his years spent in the Middle East meant he had strong views regarding the ever-evolving circumstances in that region. ‘He was of the opinion … that Israel was to have a homeland within Palestine, not Palestine as a homeland’ according to Mark, and this cost him more than a few portrait commissions in Syracuse.

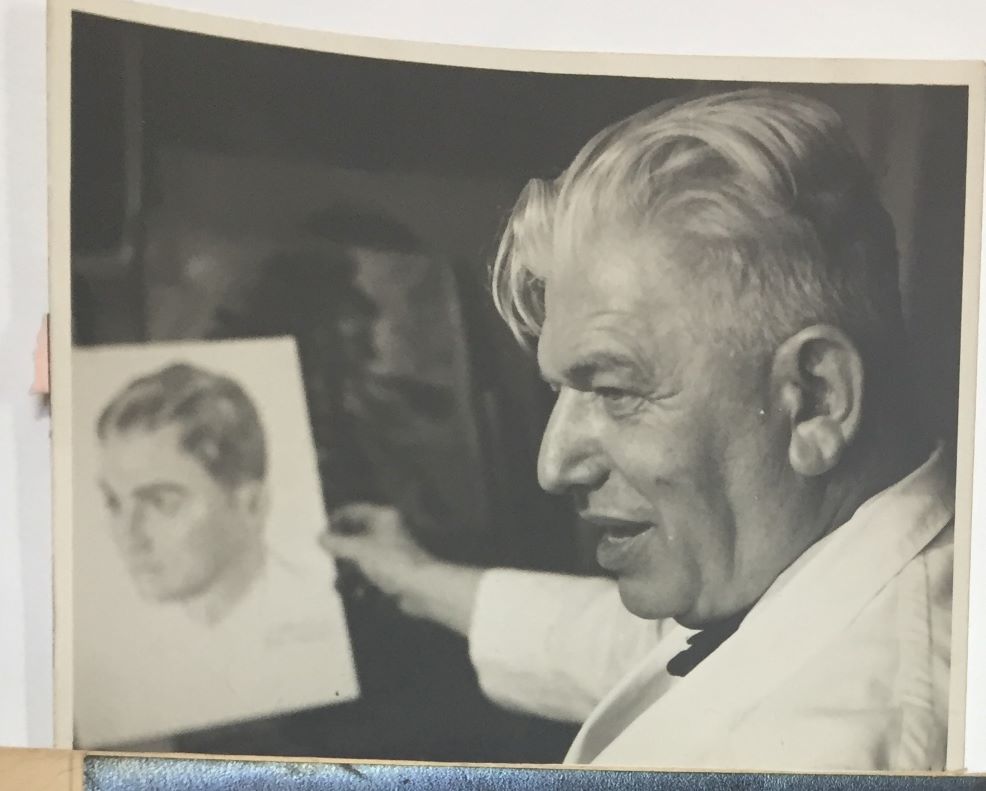

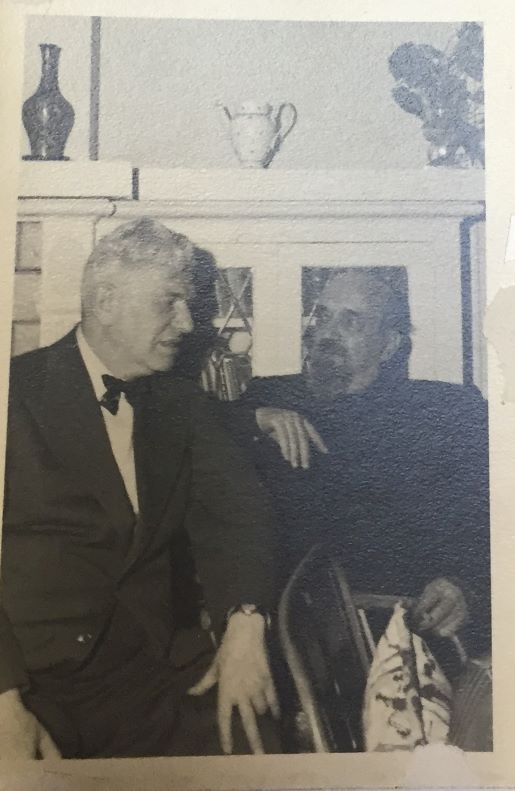

Robert Hofmann with Ivan Mestrovic at a party in Syracuse. Robert greatly admired Mestrovic's work.

Robert Hofmann with Ivan Mestrovic at a party in Syracuse. Robert greatly admired Mestrovic's work.

Mark introduced Robert to James Skvarch – another budding artist – and the three remained close friends until Robert's death in 1987. Mark and James were regular visitors to Robert's studio. As an artist, Mark remembers Robert as a humanist and a realist – literally and figuratively – with a confident, easy-going manner. He admired Salvador Dali, John Singer Sargent, and the sculptor Ivan Mestrovic; he was an opera buff – even singing to his clients as they sat for portraits; and he was quite well-versed in American cinema. The rental agreement covering the building in which he had his studio allowed him to watch films in the on-site theatre for free. One of his favourites was Lawrence of Arabia – he had, after all, fought against Lawrence and the British in Palestine decades earlier.

‘He would say "one must be taught to see"’, writes Mark, and he spoke of an 'energy' that he felt emanating from people as he painted them, saying there was a certain 'vibe' in this interaction. Robert's life spanned nearly a century, spent across three continents and many more countries. He could make himself understood in seven languages. He was a soldier, artist, refugee, immigrant and teacher. ‘What I learned and was taught from Robert’, Mark reflects, ‘was to work from life’.

All images © Estate of Robert Hofmann

Author: Elisabeth Lebensaft, Christoph Mentschl and Kate Garrett