Gerhard Viktor Boronowski was born on 22 June 1917 in Swiztochlowice, Upper Silesia, Poland. This town was part of Germany at the time of his birth. In 1936 he was identified as a socialist and antifascist assisting persecuted families. Subsequently, he fled Poland to Prague, Czechoslovakia. Between 1936 and 1939 he attended Brno Technical School.

Nazi aggression increased significantly in 1938 with the Anschluss in March, the annexation of the Sudetenland, the horrors of Kristallnacht on 9-10 November, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany on 15 March 1939.

Gerhard, along with many other pacifists, socialists and antifascists fled Czechoslovakia. He returned to Poland where the English consulate in Katowice, Poland, directed him to the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, later known as the Czech Refugee Trust Fund. He and his father, Viktor, who was living in Poland at the time, obtained refugee assistance and passage to England via Sweden.

Some time between April 1939 and May 1940, he met Margarethe (Margot, Margaret) Emma Kleiner, a Swiss citizen who was working in England as a nanny in order to improve her English. When war was declared by Britain she joined the Royal Air Force in London, England. Margot was fluent in English, German, French, and Italian, and quickly rose to the position of sergeant, working as a radio operator translating intercepted radio transmissions.

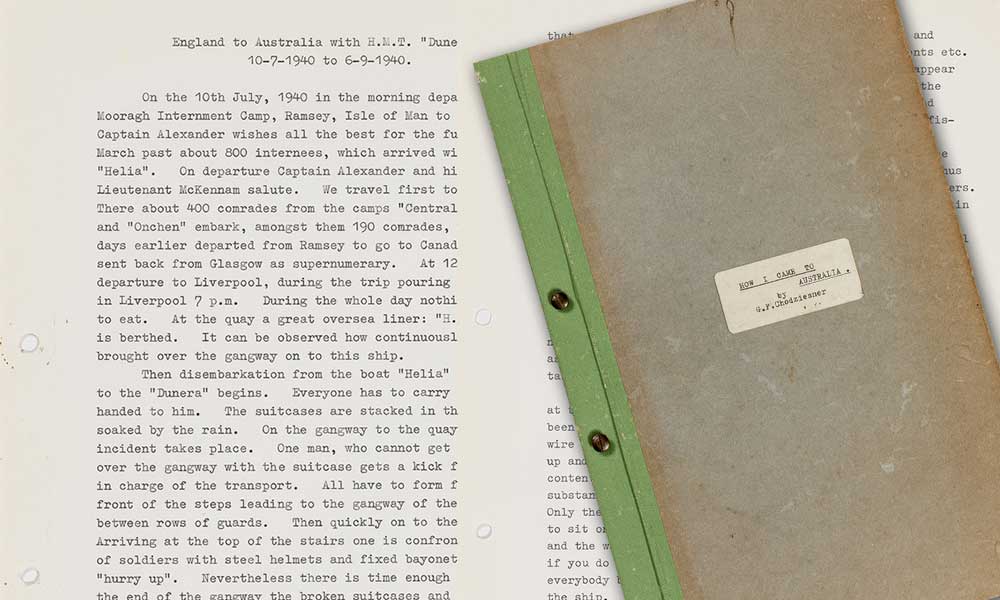

On 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland. Britain declared war and people became very suspicious and fearful of foreigners. On 16 May 1940 Gerhard and Viktor, his father, were arrested and interned. On 10 July 1940, they boarded the Hired Military Transport (HMT) Dunera. Eight days before the ship’s departure, the Arandora Star, carrying detainees to Canada, had been sunk.

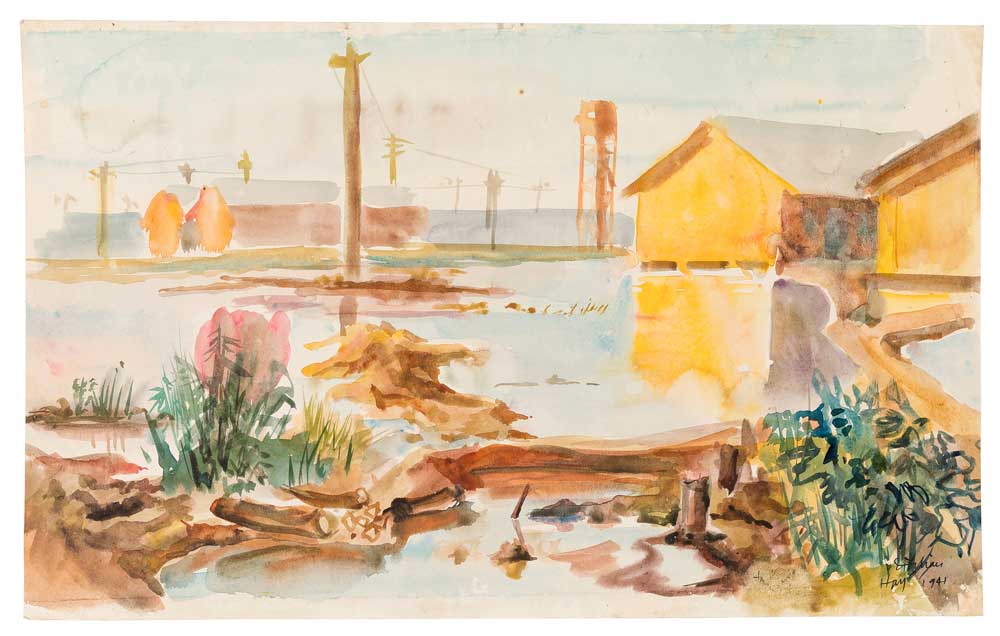

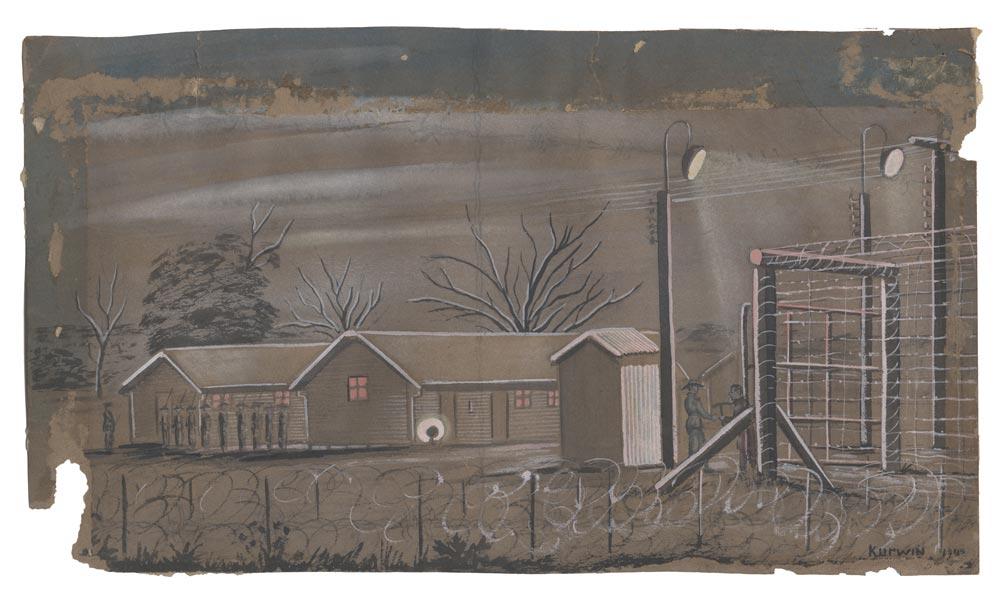

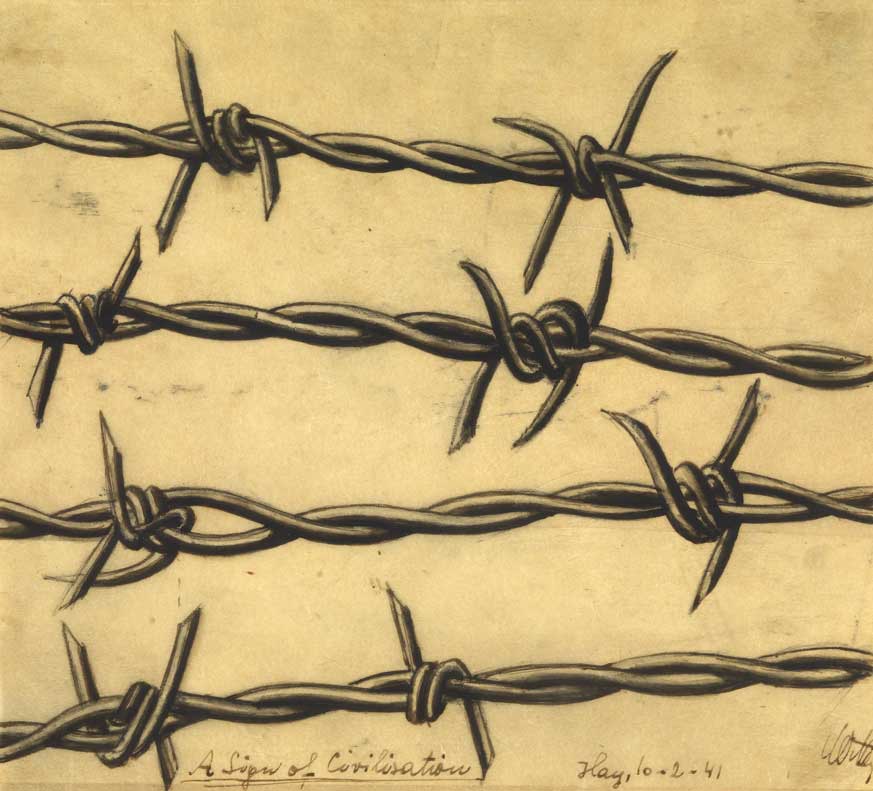

The Dunera reached the west coast of Australia in late August, and Sydney on 6 September. The next day the men were transported by rail to Hay. Gerhard was registered as internee E39202, Camp 8, Hay, New South Wales, Australia.

Records from the National Archives of Australia indicate that he and Viktor were transferred to Orange on 22 May 1941, to Tatura on 24 July 1941 and then to Wayville, South Australia, on 17 November 1941, where they waited for their release and return to England. On 7 December 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japanese forces. By this time, Gerhard and Viktor were on their way to Britain, having sailed from Australia on 20 November on the Largs Bay. Gerhard and Viktor most likely landed on the Isle of Man and were released by mid-May 1942, because, by 2 June 1942, Gerhard had obtained a job as a miller for London Grinding Limited.

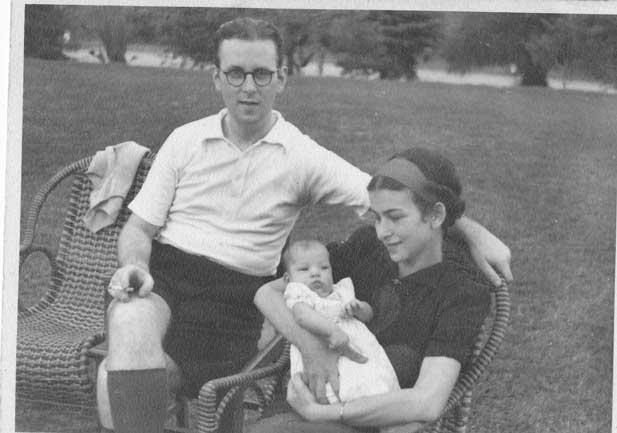

Gerhard and Margaret married in London on 14 October1943. Their marriage certificate shows Joseph (Josef) Wiora, a fellow Dunera man, was a witness and signatory at the wedding. Peter, Gerhard and Margaret’s first son, was born in London on 25 June 1944.

During the war Gerhard’s three brothers were in the German Navy. One brother, Herbert, was killed during the war. Joseph was a submariner and Fred served on a ship. Divisions within families during wartime is fairly common. The healing process took years, but eventually links within the family were recreated and by the 1960s Gerhard and Margaret were visiting relatives in Germany and Switzerland.

Gerhard was a patriot and wanted to return to Poland after the war to help with the rebuilding of the country. Between October and November 1945, Poland’s General Consulate in London issued passports for the family to return to Poland. On 9 November 1945 the family left England for Poland.

Between 1945 and 1950 Gerhard worked for the Nationalized Consumer Cooperative and in 1949 he was elected as leader owing to his skills and popularity. The Communist Party saw things differently. They questioned his management skills and dedication to the Party and he was accused of working against socialism. He was assigned to a temporary position as an accountant. Expecting to be arrested he decided to escape Poland. Gerhard was probably fearful for his safety and therefore he never returned to Poland to visit relatives or friends.

On 17 July 1950, the family fled Poland to Hamburg, Germany. The family now included me, Alexander, Gerhard and Margaret’s second son. I was born on 6 May 1948 in Tarnowski-Gory, Poland. Gerhard pretended to be a German national rather than a Polish national because it was rumoured that the Polish Mission in Germany had access to lists of Polish nationals who fled Poland and had arrived in Germany. He was worried that there could be severe consequences for his mother and father in Poland, once the Polish Mission determined that he had fled. The family received refugee Identification cards and German passports. His decision to pretend to be German caused problems later when the family sought assistance to emigrate to North America.

On 21 September 1950, the family received three-month visas to visit Margaret’s parents in Uster, Switzerland. The family arrived in Switzerland on 1 October. On 2 December that year, Gerhard returned to Hamburg to find employment; the Swiss government would not give him a working visa. Meanwhile, the German government had determined that Gerhard was in fact a Polish national and refused to issue him a work visa. Subsequently, German officials requested that his refugee identification document and passport be returned. Now Gerhard faced the fear of being returned to Poland by Germany or Switzerland. As well, his parents were still living in Silesia and, therefore, both families were worried about their safety as a result of the possible extradition. On 20 December 1950, Gerhard returned to Uster to be with his family and request extensions of their visas. Extensions were granted on 1 April 1951.

On 7 June 1951 the family was denied assistance by the International Refugee Organization in Geneva, Switzerland. The decision was based upon the fact that Gerhard was considered a German national at birth and had declared himself German when fleeing to Germany in 1950. Additional, negative circumstances were that his brothers had served in the German military during the war.

From April to November 1951, Margaret submitted emigration applications to Commonwealth countries. Her service in the Royal Air Force during the war allowed the family to emigrate to Canada, the country of their choice. One of Margaret’s sisters, Rosel Gurtner and family, lived in Bellingham, in the American state of Washington, which is very close to Vancouver, Canada. They supported us as well as possible. It was always a thrill to have the family visit us. Later, once we had moved to Canada, they would often bring jams, preserves and gifts for Peter and me.

In September 1951, the family embarked on the SS Canberra from Cherbourg, France, to Montreal, Canada. Margaret was pregnant and miscarried during the voyage. The ship docked in Quebec City on 3 November 1951, where the family disembarked in order that she could get medical assistance. She required emergency care and blood transfusions, which completely drained the family finances. The Salvation Army assisted the family, and when she was well enough to travel the family continued westward by train to Vancouver. The family never forgot the generosity given by the Salvation Army and we have contributed annually to this marvellous organization.

We arrived in Vancouver and there, waiting at the train station, was a recruiter who offered Dad work at Singapore Best Spice factory. Our first home, was a cold damp basement suite in a house on Lulu Island, Richmond, British Columbia. My brother, Peter, remembers frost on the cement walls during that first winter. Mum felt that some of her arthritis was due to living conditions during those early years in Canada. Dad and Mum worked as labourers at a fish plant in Steveston, Richmond, picking blueberries and cleaning houses.

The following year Dad obtained a job in a dairy plant in Vancouver. We moved to South Vancouver and into a basement suite of an old house with several small apartments. Dad was the caretaker of the house and he was responsible for starting the fire in the wood and coal furnace before going to work. Life was much easier for the family. Peter began school and I was cared for by babysitters while Mum went to Vancouver Vocational institute, where she studied for a diploma as a Practical Nurse.

It was very unfortunate that Mum and Dad couldn’t combine their extensive life and language skills with employment. Our parents worked very hard and taught us the virtues of hard work, independence, honesty, punctuality, thrift, sharing, kindness, tolerance, education, eating healthily, and cleanliness. They both loved music and had a wonderful record collection and season tickets for the Vancouver Symphony. One of our favourite outings involved taking the bus to Stanley Park where we picnicked, walked and played in the salt water pools. In 1955, Mum and Dad bought a new Ford Consul car, which expanded and made easier our ability to shop, reducing the time spent on long commutes, and allowed more time for leisure, including exploring the mainland and beyond. That was also the year that I started school. My brother and I were ‘latch key’ kids. School photographs would show kids with keys strung around their necks. We would come home to peel potatoes and have everything ready for our parents to enjoy a cup of tea.

In 1956, the old house had to be fumigated and shortly thereafter we moved into the basement of an apartment building in Marpole, a suburb of Vancouver. Mum and Dad shared the vehicle, their work shifts such that one of them was at home soon after school was out. Dad’s jobs were not very secure and he got laid off a few times during recessions.

In 1957, the family purchased their first home in South Vancouver, not far from the Fraser River. The house was small, old, set back on the property lot, and very close to the back alley. But it was wonderful and had a garden that was loved by the family. We finally felt our roots were established. Dad and Mum both took night school courses, mainly ones that could be applied to improving our lives. Dad started renovations, which included electrical and plumbing upgrades. For a short period he worked for a stone mason and learned enough to build stairs, flower and shrub rockeries, a chimney, retaining walls and a patio from granitic rocks that were collected during excursions with our vehicle or a borrowed truck. Dad and Mum introduced us to Vancouver’s public libraries and Dad was constantly reading books on subjects such as how to lay hardwood floors, replace car brakes and clutches, replace windows, and design a safe carport. These were great years. By the late 1960s, they had discretionary income for travelling to Europe to visit family and friends.

Dairyland Ltd. sent Dad to a laboratory course in order to become a laboratory technician at its plant. He worked in the laboratory but then decided to return to a labourer’s job in the plant because the union job paid much more. In retrospect this was a mistake, because health problems were appearing that eventually forced him to retire early.

Snowfall at our first home in South Vancouver. Background shows the rock work completed by Dad.

Snowfall at our first home in South Vancouver. Background shows the rock work completed by Dad.

Peter and I both attended the University of British Columbia where Peter graduated as a medical doctor and me as a geologist. While at university we were in the University Naval Training Program and on completion we were commissioned as officers. We both put ourselves through university, but it wouldn’t have happened without our parents’ support – a home, food and even an automobile to drive to school each day. Our family is very thankful to Canada for accepting us as citizens and Peter and I were proud and willing to serve our country as reservists.

In the early 1970s, Mum and Dad sold our original home and purchased a lovely home in North Vancouver closer to the forests and mountains, which they loved and walked through while searching for mushrooms, or walking with the grandchildren or the dog. The garden was much larger and the house was significantly more spacious and comfortable then their previous home. Retirement was good and gave them time to socialize with friends. Mum joined a church choir and exercised regularly with other senior ladies. Dad remained more of a loner and enjoyed his times walking, shopping and seeing the grandchildren. Summers were often spent with Peter and his family at their cabin near Lund, British Columbia. Dad and Peter became good fishermen and enjoyed being out on the salt chuck or, at low tide, collecting oysters and crabs for a meal.

Eventually, Mum and Dad decided to move into an apartment not too far from our home. Unfortunately, Dad had serious blood circulation problems. On 26 January 1993 he was rushed to hospital and died quickly from blood loss due to a burst aorta.

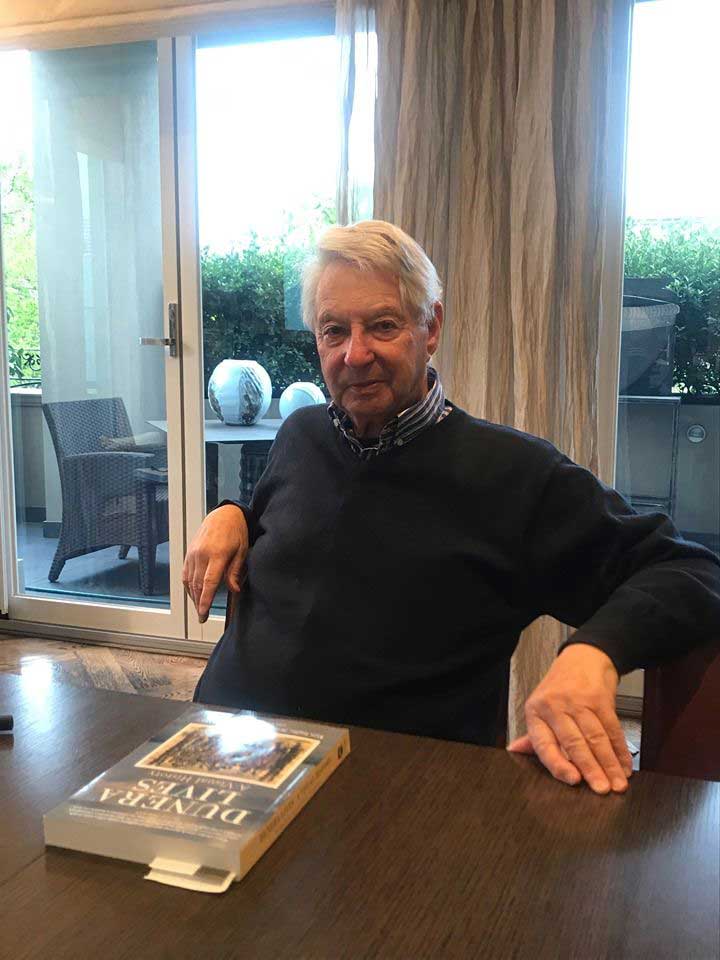

Dad never became involved in politics after arriving in Canada and rarely spoke about the war other than the suffering and waste that wars create. He only mentioned his internment in Australia and the ship that took him and his father to Australia. It was only recently that I was watching a film on the Dunera boys when I turned to Linda, my wife, and said ‘that sounds similar to what my father told us’. I spent until the early hours of the morning searching the National Archives of Australia where I found documentation regarding my father and grandfather. It was amazing to see his signature and handwriting, and biographical information such as his next-of-kin. I wish that I had known more about the Dunera boys earlier. Perhaps I could have accompanied my father to a reunion.

My parents were not famous or exceptionally talented but they provided for a comfortable and stable environment for Peter and me. I would guess that their lives are not much different from many of the other Dunera boys who settled in various countries around the world and whose legacy are their children and grandchildren.

This article was written by Alex Boronowski, son of Gerhard and Margaret Boronowski. The information comes from documents in the National Archives of Australia, Arolsen Archives, and personal recollections, including those of Peter Boronowski, Alex’s brother.

All images © Boronowski family

Author: Alex Boronowski