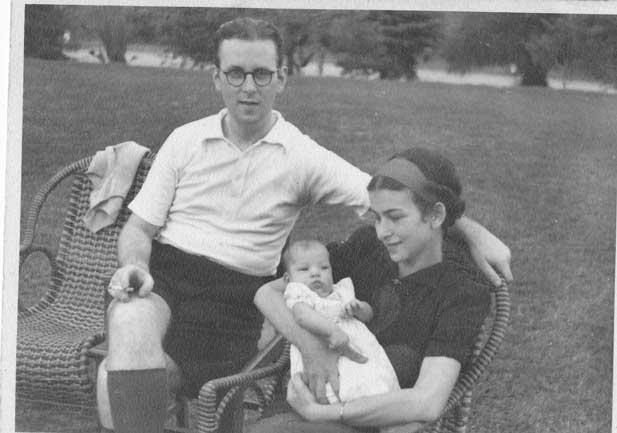

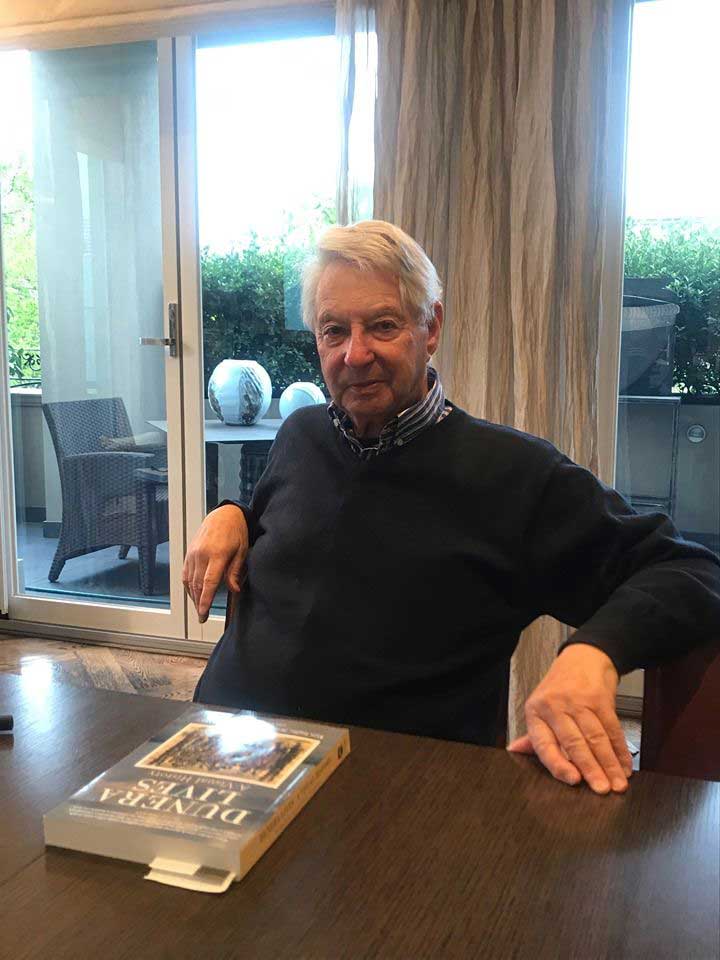

Günter Altmann was born on 28 December 1918 and was just 21 years old when he was detained in Britain and deported to Australia aboard the Dunera. And though his older brother, Paul Altmann, was also aboard, their lives up until then and in the years that followed would diverge in many ways: Paul and Günter had been living in different cities in Britain and were only reunited when, by happenstance, they were assigned to the same deck on board the Dunera; later, Paul chose to remain in Australia following internment, while Günter and his Australian wife joined his parents in Brazil.

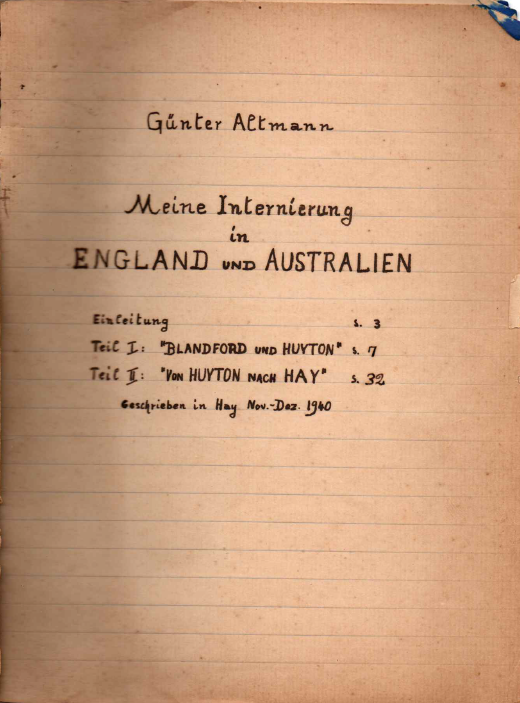

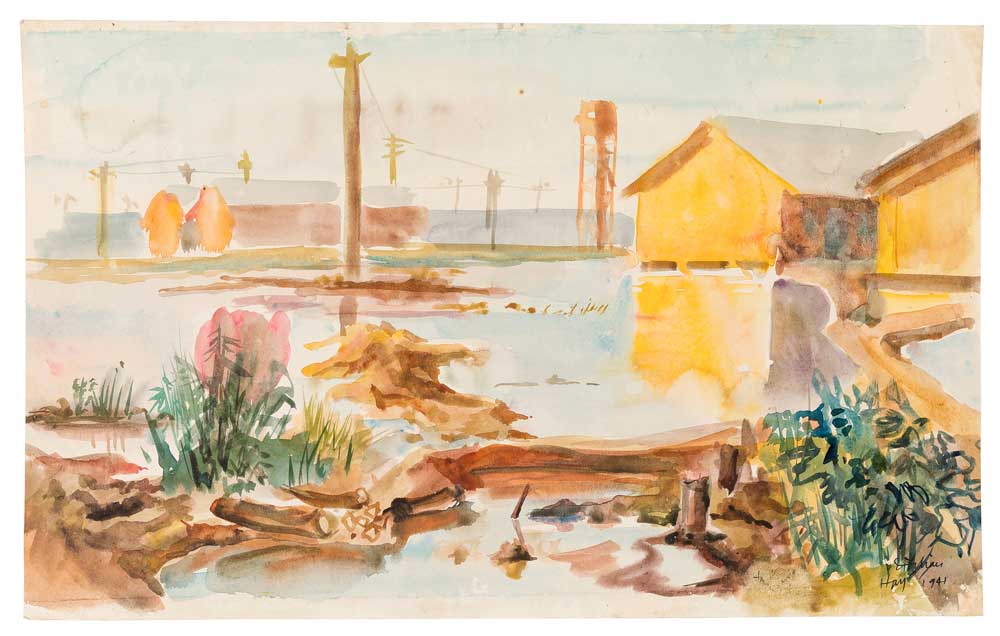

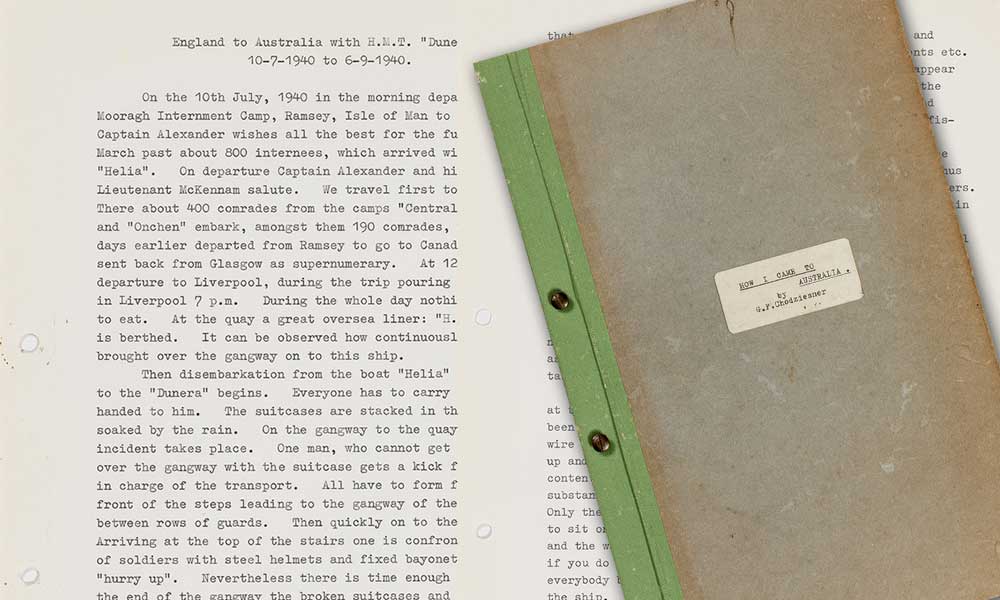

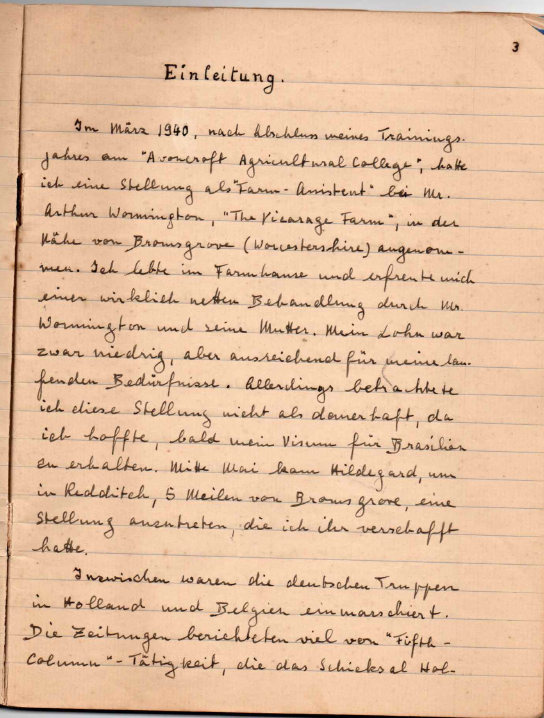

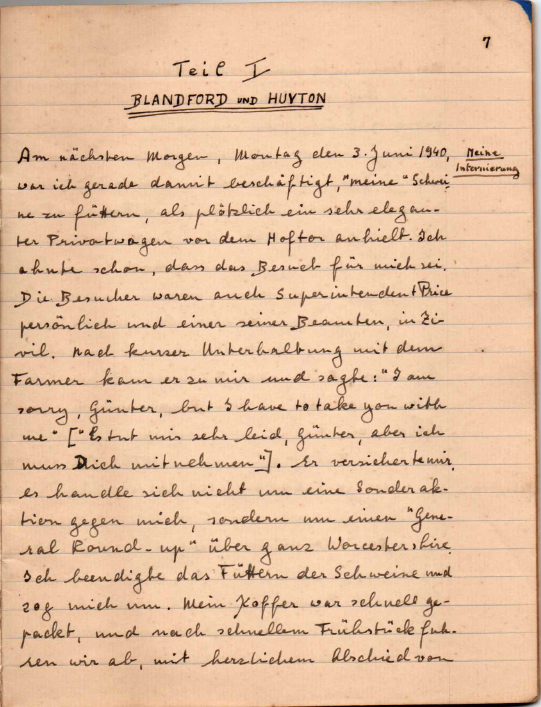

What follows is a rare and unique document, which Günter wrote in his native German while interned in Hay, New South Wales between November and December 1940. In Günter's own words, it "is not meant to be a diary... but instead an attempt to record the memories of this journey that have remained in my mind."

The document is split into two main sections: Part I, Blandford and Huyton and Part II, from Huyton to Hay. This is Part I.

Translator's note:

This is a translation of an original handwritten document. For the sake of readability and consistency, some small changes have been made (ex. incorrect English spelling has been corrected and numbers and dates have been made uniform). The most notable change is that the name of liaison officer, John O'Neill was, in all but one instance, misspelled throughout the entirety of the original diary (O'Neil rather than O'Neill). Otherwise, the translation sticks closely to the original document and all capitalisation, usage of inverted commas, inconsistencies and incorrect information is a true reflection of the original.

In March 1940, after finishing my year of training at ‘Avoncraft Agricultural College’, I took a position as a ‘farm assistant’ with Mr Arthur Wormington at ‘The Vicarage Farm’, near Bromsgrove (Worcestershire). I lived in the farmhouse and was treated very well by Mr Wormington and his mother. Though my wages were low, they were enough to cover my ongoing needs. However, I did not view this position as a permanent one because I was hoping I would soon receive my visa for Brazil. In the middle of May, Hildegard came to take a job I had gotten for her in Redditch, five miles from Bromsgrove.

In the meantime, the German troops had marched into Holland and Belgium. There were many reports in the newspapers about the ‘fifth column’ activities that had sealed Holland's fate as well as Denmark's and Norway’s not long before. As a result, the English press felt obligated to stoke sentiments against foreigners in England, with the victims being, in particular, the ‘refugees’ from Germany and Austria - around 60,000 to 70,000 people of all ages. The agitation within the press culminated in the demand: “Intern all Aliens”, and one day, the Home Office officials lost their minds and began randomly interning people between the ages of 16 and 70, initially in specific coastal regions, which were declared ‘protected areas’.

At first, only particularly suspicious people were interned in the non-coastal parts of the country. Others were placed under special police surveillance. Of course some people used it as an opportunity to denounce foreigners they found unpleasant for whatever reason and get rid of them. It seemed someone wanted to do that to me. At any rate, one day I received a visit from a police officer, who explained to me that “SOMEONE” had accused me of highly suspicious activity. Among other things, I was meant to have signalled to planes and other similar nonsense. The police officer knew me and so the matter was quickly dealt with, in part because Mr Wormington also spoke up for me. It was a bit embarrassing, though.

On 27 May, my friend Manfred Löwengard was arrested in Bromsgrove and interned. After that, I thought to myself: it’ll be your turn soon; and I wrote to my parents in Brazil, telling them I expected to be interned any day. In the middle of the week, there was an announcement on the radio about a ‘curfew’ for foreigners, which would come into effect on Monday, 3 June. We were no longer permitted to own cars or bikes, among other things. That was very unpleasant, as my bike was my only means of getting to Bromsgrove, where I had a lot of friends, or to see Hildegard in Redditch. So I put in an application with the police for a special permit to keep my bike and Mr Price, the superintendent of the Bromsgrove Police, passed it on for approval. In the meantime, he permitted me to continue using my bike. On Sunday, 2 June, I rode to Droitwich with Hildegard to go swimming, and we had a pleasant and relaxing afternoon; the weather was wonderful and we ran into a few good friends while we were there.

The next morning, Monday, 3 June 1940, I was feeding 'my' pigs, when suddenly a very elegant private car stopped in front of the yard gate. I already suspected that the visitors were there for me. The visitors were Superintendent Price himself and one of his officers, dressed in street clothes. After talking briefly with the farmer, he came to me and said: "I am sorry, Günter, but I have to take you with me". He assured me that I was not being targeted in particular, but instead, that this was a ‘general round-up’ across all of Worcestershire. I finished feeding the pigs and then got changed. I packed my suitcase quickly and after a quick breakfast, we drove off, with a warm farewell from Mr Wormington and his mother.

At the police station in Bromsgrove, I met three former friends from college, and together we were taken to the police headquarters in Worcester in a police car (but not a 'paddy wagon'). We received a small lunch there and then a military escort took us, alongside other recently interned people - around 20 in total - by train through Leicester and Bath to Blandford (Dorset), 15 miles north of Bournemouth. There, we were packed into a truck and were driven to the INTERNEE COMPOUND of the INFANTRY-TRAINING-CENTRE 297 (?), a field exercise camp with 25000 men.

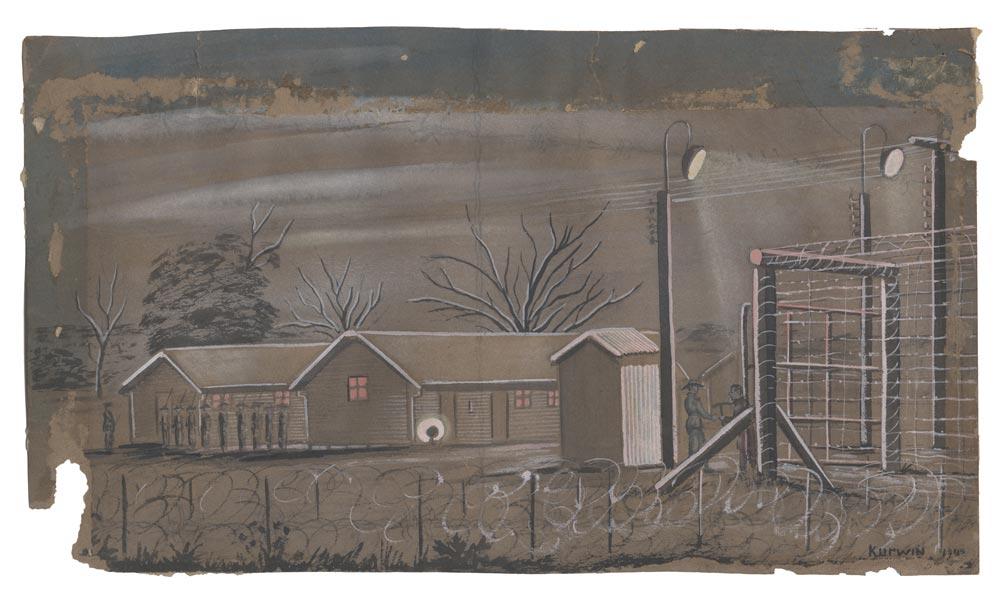

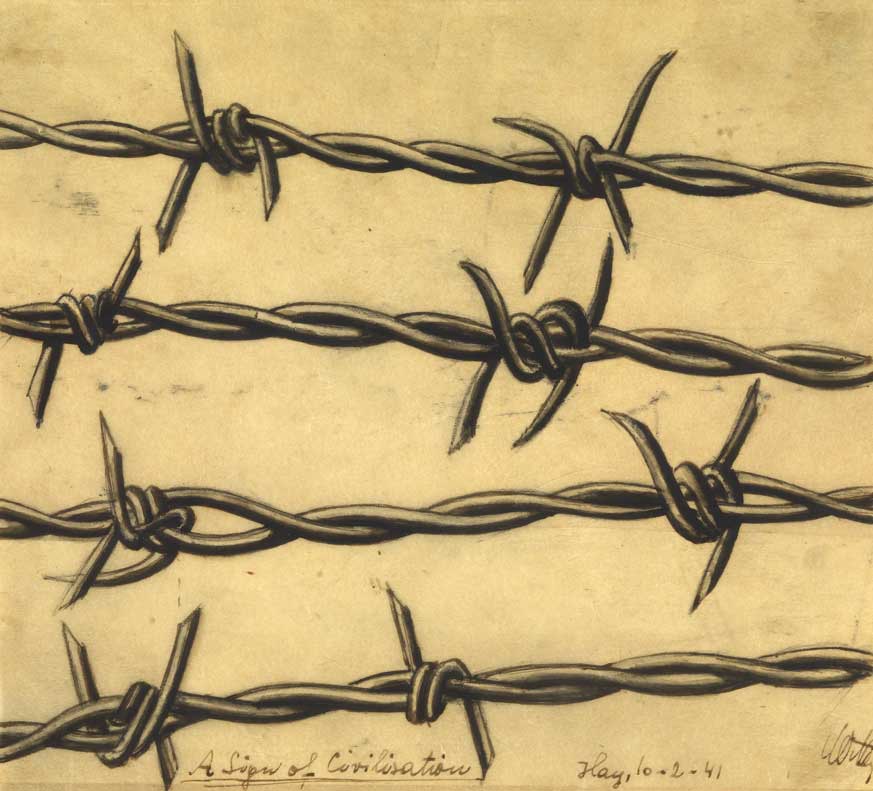

The 'I.-Compound' was made up of three huts for living quarters and one hut for meals, all of which were surrounded by a barbed wire fence. In one hut, we found three old men, almost 70 years old, who had arrived from Bournemouth the day before and were now terribly depressed. The majority of us were young people and soon things grew a bit livelier. We received nice mattresses, white bed linen and very decent blankets. The people over 60 also got bed frames.

The camp was located on hilly, chalky soil, which still showed significant evidence of its oceanic origins. Covered with a thin layer of dirt and short turf - just enough to feed a few sheep - everything got dreadfully dirty in the rain. But for the majority of the time, we had lovely, hot weather.

Every few days, new people arrived, the majority of them from the south west of England and from Birmingham. In the end, we numbered 104 men. We chose as our leader and speaker a Viennese man, a former officer, Marcel Nemenji, who was a calm, distinguished and even-tempered person in his mid-40s. He knew how to win over our officers in a dignified manner, so that we were protected from all the harassment in this camp.

In general, we were treated quite decently. We could buy newspapers every day, something we were very occupied with during those weeks in particular. The soldiers or our Orderly Corporal could also get us cigarettes, chocolate, fruit, etc. from the soldiers’ canteen, and a few times our Sergeant Major drove to Bournemouth to buy us toiletries, books, etc.

We were taken for walks two to three times per day. That meant we were escorted to the edge of a small forest, where we spent one to two hours in the field playing ball, doing athletics and wrestling. The soldiers guarding us were, with very few exceptions, always friendly to us as soon as they understood that we were not 'fifth columnists' but rather 'refugees from Nazi oppression'.

We were visited repeatedly by the various military chaplains, who brought us books and newspapers. Once we were taken to a military service in a church. To our left and right stood guards with bayonets, but the chaplain soon indicated that these must be lowered.

It was interesting to observe how all the new arrivals initially suffered from an attack of barbed wire psychosis. They were depressed and nervous for two or three days and wanted to protest everything. But most soon calmed down and resigned themselves to their fate, and only a few people demanded to see the Swiss Consul as the representative of the German government.

Getting through these first few weeks of internment was thus relatively easy. However, there were various unpleasantries, of course. The worst was the issue of the post. The censorship regulations were very strict and seemed to change every day, so you never knew if the letter you wrote today would leave the camp tomorrow.

In the meantime, the B.E.F. (British Expeditionary Force) had been evacuated from Dunkirk, narrowly escaping the complete annihilation that threatened following Belgian capitulation. The German Army had broken through the Maginot Lines at Sedan, had set up so-called little Maginot Lines (on the border between Belgium and France), and was now threatening to advance quickly and surround the French from behind, across from the Siegfried Line. On 10 June, when France’s fall was more or less certain, Italy also declared war without having achieved any victories over the already defeated foe. After quick advances in the middle of June, the Germans now occupied Paris, the Reynaud government had toppled and the new Petain government requested an 'honourable' ceasefire on 19 June.

Since the German Army's advances were unstoppable, the French had to capitulate in order to avoid complete annihilation. On 21 June, in the forest of Compiegne (at 3:30 in the afternoon), Hitler, with much pomp and circumstance, dictated to the French parliamentarians his conditions for the armistice, which had to be accepted within 24 hours. On 24 June, the Italian conditions were accepted, and the ceasefire went into effect on 25 June at 00:35.

These events allowed for the German Army to gain access to the channel ports. That meant that the route to England had grown very short for the German bombers. We follow these events with heightened tension, listen to Churchill's speech on the radio, in which he declares that England will continue to fight and dismisses the French assertion that England have abandoned their allies.

The German army command wastes no time. No sooner is the peace agreement with France signed, German planes launch their first major air raids on England. There's an air raid siren in the night between 19 and 20 June. I wake up at 12:30 at night because someone is shaking my arm. Suddenly, I become aware that an alarm is shrieking nearby. It's a sound that shakes you to your core, and which is not easy to forget. A triad, constantly rising and falling, it lasts for two minutes and, in and of itself, creates an atmosphere of the utmost tension.

By the time I am completely awake and realise what is going on, everyone is already on the move. I am dressed before the siren stops and lie back down on my mattress again, having decided to not let anything upset me. A guard runs up outside, and we are given strict orders to remain in the huts.

The siren fades, and suddenly there is a breathtaking stillness. Everyone is listening intently for any sort of noise. An observer at the window sees flak fire in the direction of Bournemouth, and now you can hear a distant growl that swells to a roar. We are almost holding our breath, trying to hear every noise. But the roar dies away; the first 'wave' has flown over. A second follows, and then more. In total, we count five 'waves', which approach, fly over us with a roar and disappear to the north, towards Wales. Soon everything is quiet and I fall asleep.

I have been sleeping for half an hour at most, when again I am woken by the sirens. Because I am already dressed, I stay lying down. Again, the growl approaches and turns to a loud roar. They are just over us now. Suddenly, a whooshing whistle that seems to be heading straight for us. It sounds like a dive bomber. I am interested to see what will happen in the next moment. I am not scared. The anticipated explosion does not come; instead, there is a sudden calm. The whistle falls silent, the growl of the planes fades away and immediately, the 'All Clear' sounds. We get undressed and go back to sleep.

In the morning, we learn that multiple bombs were dropped on our football field and that they exploded after a few hours damaging nothing.

On the 24th, Captain Whaley, the camp adjutant told us that we should prepare to be taken away within 48 hours. 'It is possible,' he said, 'that you will go to Canada'. Some of us were very excited, but some grew quite agitated. When asked about it the next day, the officer said he did not know anything about Canada. In the evening, I had the honourable task of organising a colourful farewell evening, which I carried out to everyone’s satisfaction.

When I think back to that 'big attack' today, the whole thing strikes me as almost ridiculous compared to the horrific air raids that London and so many other cities have faced since the end of August. It is very difficult to imagine something like that; one can only guess at the horror of these events from photos in the newspapers.

During the second to last night in Blandford, a few minutes after the 'Cease Fire' in France, there was another air raid siren. Once again, we heard the planes roaring past overhead, but no bombs were dropped. During this 'raid', we noticed that they sounded the ‘All Clear’ at the beginning and ‘Warning’ at the end, which they realised partway through and changed.

On 25 June, we were loaded onto a train. Thanks to the competence of the officer in charge, we almost missed the train. At any rate, some of our luggage and our lunch remained behind at the station. We travelled through Bath, Leicester, Bromsgrove, Birmingham to Huyton, near Liverpool.

A.I.C. (Aliens Internment Camp) Huyton is a transit camp, which can hold a maximum of 4500 men. The first 1500 of them live in houses, without any furniture or lights. The remaining 3000 sleep in tents, on thin straw sacks with two blankets at most. Some of the tents are not even surrounded by moats. Because of the ongoing rain, it is almost impossible to stay in these tents, but only after long negotiations do the military authorities permit at least the older people to sleep in the mess huts.

A few days after our arrival, a group of 400 men leaves; it is believed they are headed for Canada. I am elected 'Tent Village Leader' in my tent village, with a crew of 120 men. The representative for the entire camp is Professor Karl Weissenberg from Vienna, a refined and likeable person, who is almost too gentle for this tough position. He is like a father to all the 'internees' and no one who goes to him, even just for advice, is turned away. His actions go almost beyond the humanly possible in the constant, exhausting battle with the senior military authorities and the cruellest attacks and suspicions from his camp 'comrades'; yet he remains friendly to everyone. He has at his side a sort of miniature Parliament, which I am part of as 'Village Leader'. There is almost as much ridiculous nonsense said in this Parliament as in a real Parliament. The sessions are usually unpleasant and generally I see my best contribution to be in saying nothing.

I become good friends with Marcel Nemenji, with whom I live with for a time and who I work closely with because he is also group leader.

The conduct of the military authorities in Huyton is very different to how it was in Blandford. The camp adjutant, Major Wights says at one point: 'You are refugees, you have no rights whatsoever.' We are treated accordingly. Upon arrival, each suitcase is searched and ridiculous objects like nail clippers and razor blades are confiscated. Documents are taken away and duly registered. Unfortunately, it’s not just the soldiers doing the searching but also repeatedly the 'internees' who have a hand in fountain pens, etc. disappearing into their own pockets.

The situation with the post is downright unbelievable. Officially, we are permitted to write 24 lines twice per week on prepared paper. But this paper is not always there, (supposedly, the company’s head engineers have been INTERNED and so there are issues with manufacturing) and if it is not there, then the internees are not allowed to write. On top of that, all correspondence between the internment camp and the outside world is held for about 14 days, so it often takes a month to get a response to a letter. But most people don't stay there for that long, since Huyton is just a transit camp. All of that heightens the agitation within the camp; in particular, because there are rumours regarding foreign women being interned and heavy bombing.

On the afternoon of 2 July, all the group leaders are called together, read a list of names, and told these people should prepare to leave the next morning with at most 40 pounds of luggage. No destination is mentioned. But right away, there are rumours that these people will be going to Canada. Many of my friends and other people my age are on the list, though I, by some fluke, am not. My friends urge me to volunteer and go with them, but I say that I do not want to pre-empt fate.

In general, the list, which contains around 600 names, has been put together completely at random and without consideration. Fathers and sons are separated, brothers torn apart and seriously ill individuals categorised as capable of travel. There is intense agitation. Only after lengthy negotiations with the most reasonable officers are we able to get some of the most severe cases removed. At the same time, as the camp representatives, we make our intense displeasure clear to the Commander and write a telegram to the 'Parliamentary Committee for Refugees'. In it, we request a representative visit us soon on the basis of the hardships that resulted from the selection and the urgency given that further transports have been announced. We give the telegram to the Commander, who, after speaking on the phone with the Chief Censor in Liverpool, decides that the telegram requires the approval of the War Office. I do not know whether it received that.

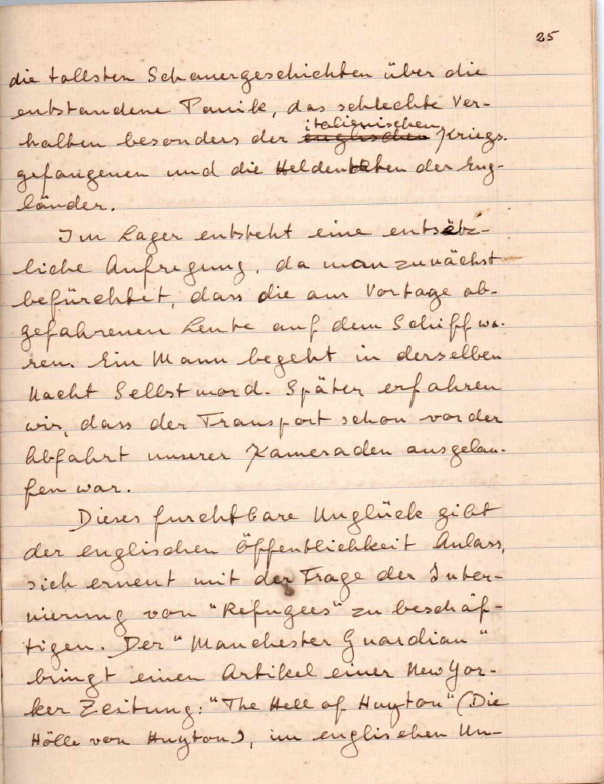

On 4 July, we hear - first as rumours and then officially - that the Arandora Star (21000 tons) was torpedoed by a German U-boot in the Irish Sea and sank with 1500 prisoners of war and civilian internees on board. Two thirds of the people are said to have drowned. The newspapers that we get in the camp illegally (from the guards) tell horrific stories about the panic that ensued, the poor behaviour of the Italian prisoners of war in particular, and the heroic actions of the English.

There is terrible agitation within the camp because at first we fear that the people who left a few days earlier were on the ship. One man takes his own life that night. Later, we learn that the ship had already left before our comrades departed.

This horrible incident gives the English public occasion to once again turn its focus to the issue of interning 'refugees'. The Manchester Guardian publishes an article from a New York newspaper: 'The Hell of Huyton'; questions are asked in the English House of Commons. In a speech, Mr Attlee makes a scathing attack on the 'Home Secretary', Sir John Anderson, over the pointlessness of interning refugees, who could be providing real service to the country, while actual enemies are walking free just because they are English. Slowly, people are beginning to become aware of the injustice done to the refugees. There is another suicide in the camp. Over the weekend, a representative of the Home Office visits the camp and after lengthy negotiations agrees - in the name of the Home Office - that in future only volunteers will be sent overseas. At the same time, he promises that the government will pay for the families of married individuals, who go overseas, to follow them.

The initial result of the shift in English public opinion is that we are made aware of some conditions that would allow for us to apply for release. I make no effort to that end, however, because I am of the opinion that it is much better for me to leave England.

One evening, we have a big concert; the highlight is Landauer, who is very well known on the radio as one half of the Rawicz and Landauer piano duo. He only plays light music but does so magnificently.

On 5 July, I get a letter from Gertrud in London, who writes that Paul was interned immediately after he finished his exam (B.Sc.). No one knows where he is.

On 8 July, they put out lists for voluntary registration to go overseas. When asked, the Commander says: 'It is very likely that the transport will go to AUSTRALIA'. I am the first volunteer. Many of 'my' people come to me and ask for advice about whether they should put their names down or not. I am of the opinion that if they have real reasons to want to stay in England, they should not put their name down; but if they do not, they have to reckon with deportation.

Within 24 hours, I am proven right. The transport is originally meant to consist of 1500 men, but after much pressure from us, this is reduced to 1100 men. Even then there are not enough volunteers. First, they try to find more by making vague promises. But when they are still 300 short on Tuesday, almost all the unmarried and a few married people are ordered to join. We are immediately told that this list is final, as it has already gone to the War Office.

Intense agitation ensues, and there are tense and sometimes aggressive discussions with the officers. But only very, very few people, who simply refuse to go, are able to get their names struck from the list.

Our camp 'Parliament' is in a sorry state during these few days. There are endless discussions about human rights, and professionals and laymen alike repeatedly bring up international law, but the group rarely proves to be capable of active and positive work. We have only the dedication of Prof Weissenberg to thank for the things we do achieve. But all of that sort of work is made immensely more difficult due to the disgraceful behaviour of the majority of the camp ‘comrades’: anyone who works in any sort of position of responsibility is attacked in the cruellest way possible and viewed with suspicion.

I also want to say a few words about the medical conditions. In this camp, where the sanitary conditions are dreadful and the 4000 people living here are thus more intensely exposed to all sorts of diseases than they normally would be, we are lacking even the most necessary of medicine. The 'hospital' is unfit for human beings. The military doctor is completely disinterested and, for example, during the night refused to see to a man, who was having a nervous breakdown and threatening suicide. With that lack of interest on the part of the authorities, it's no wonder that cripples and the seriously ill are declared capable of travel and must undertake the onerous journey overseas.

On Wednesday, 10 July, we leave the camp after lunch and are loaded onto a train. We do not know what our next destination will be. That does not bother me much. As always, I am in a good mood and 'novarum rerum cupidus'! My 'cupiditas' shall not be disappointed.

All images © Margaret Riederer

Author: Translated by: Kate Garrett