Johann Joseph (Hans) Rothe was born in Vienna on 10 April 1905 to Leopold (b. 1854) and Juliane Rothe, nee Engelhardt (b. 1874). His parents married in 1893, and appear to have moved between Sarajevo and Vienna. Leopold was an official with the Union Bank of Bosnia and the Herzegovina, and it seems that Hans may have spent some years in Sarajevo. The Rothes were Catholic. Some Dunera internees of Christian faith came from families that had converted from Judaism, but Hans seems not to have had any Jewish ancestry. Around 1911 the Rothe family left Vienna; for where isn’t known.

In 1939 Rothe was living in Surrey, looking for work as an advertising designer. He may have been employed as a painter in the film industry. British authorities declared him a non-refugee, though the label should be regarded with caution: inefficiencies and mistakes characterised the work of the ‘enemy alien’ tribunals. Other evidence suggests he was a refugee. He came to Britain from Prague under the auspices of the Czech Refugee Trust Fund, and lived at Shenley House, Red Hill, Surrey, where many refugees had lodgings. Rothe was arrested at Red Hill on 16 May 1940 and two months later deported to Australia on the Dunera. On entering Australia Rothe listed his occupation as ‘cartoonist’; gave his name as Hans, making no mention of ‘Johann’ or ‘Joseph’; and named Miss Ellen Boxhorn of Reigate, Surrey, to whom he was engaged to be married, as his next-of-kin.

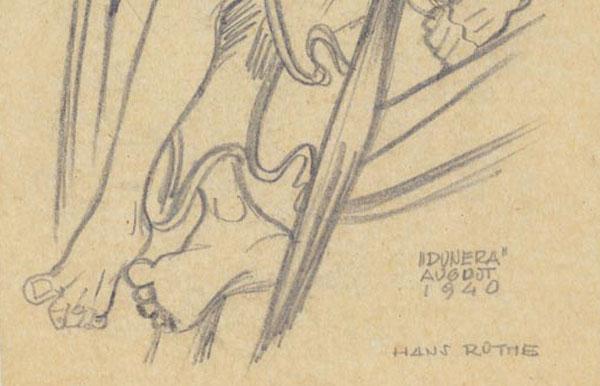

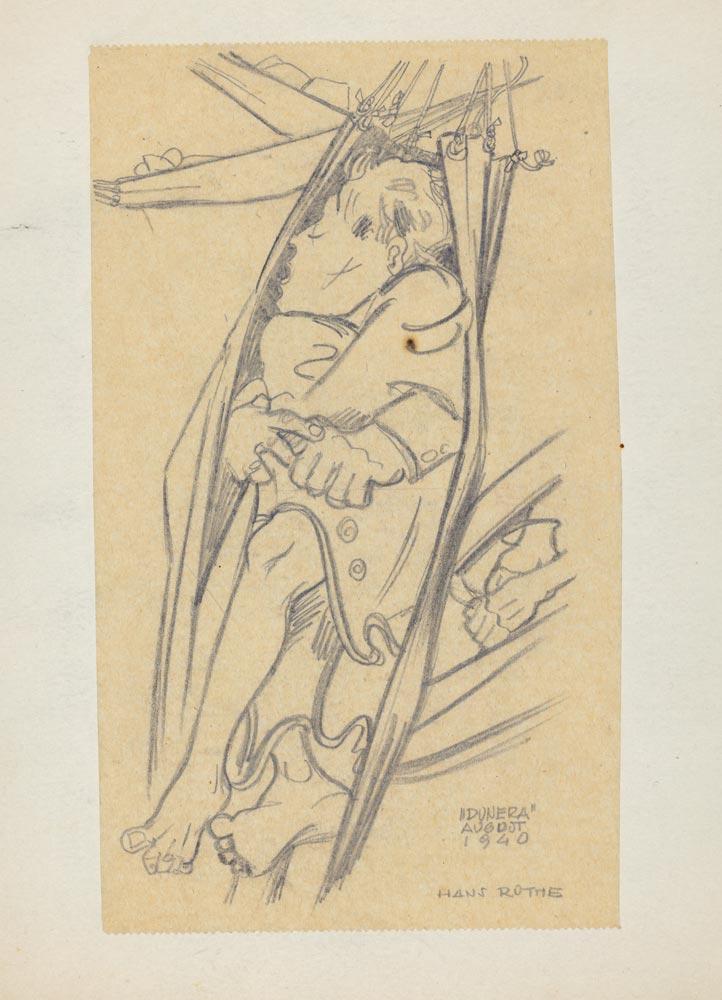

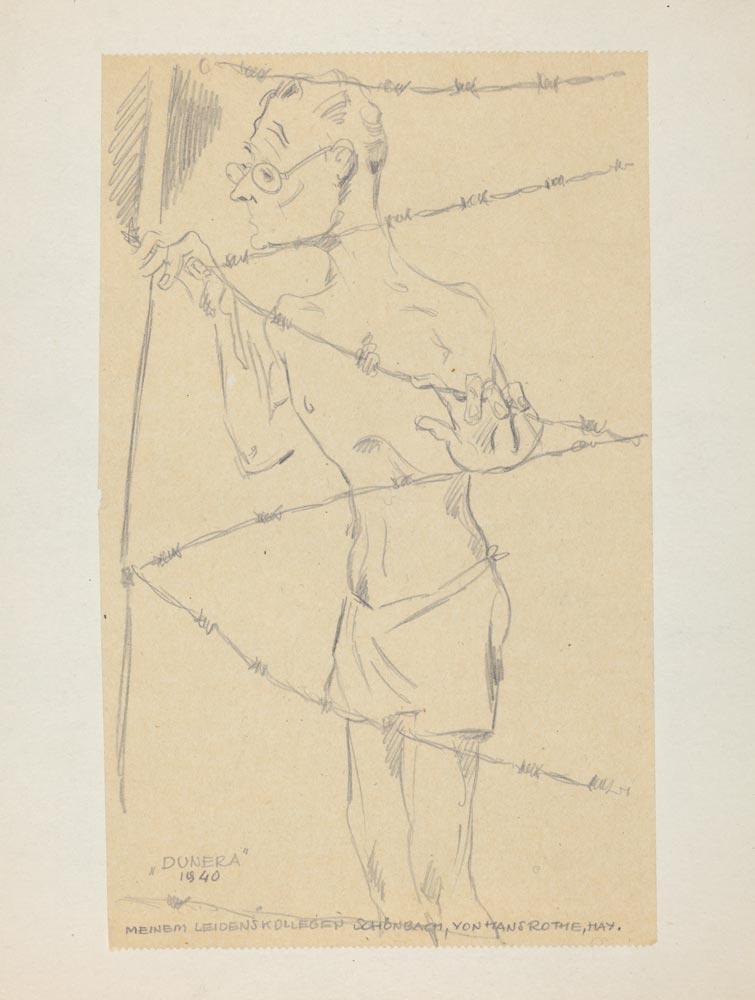

Rothe depicted the chaos, despair and sadness he saw on the Dunera. Several of his sketches survive from this time. One is in a private collection in Canberra, and two (shown here) are with Gabriela Schonbach in Vancouver. She inherited the sketches from her father, Fred, who was interned with Rothe at Hay. The inscription on one of the sketches – ‘My fellow sufferer Schonbach’ – suggests they shared burdens and friendship, though their connection seems not to have survived internment: Gabriela does not recollect her father mentioning Rothe. Both drawings show vividly the physical and emotional vulnerability of internees aboard the Dunera. Neither could be described as a cartoon.

'Meinem Leidenskollegen' - 'My Fellow Sufferer' - Hans Rothe 1940

'Meinem Leidenskollegen' - 'My Fellow Sufferer' - Hans Rothe 1940

At Hay Rothe was held in Camp 8. He sketched cartoons, some confronting and deliberately stark, others sardonic. In one (Dunera Lives, vol. 1, p. 134) a drowning internee, perhaps Rothe himself, pleads for release. Rothe spent time in the hospital at Hay, then in May 1941 went with 400 other internees to Orange, which could indicate he was still sick or recovering from illness. Recuperation was one of the reasons internees were sent to Orange. In July he was moved with the Orange internees to Tatura, and on 15 October 1941 he sailed for England, where he was to be released. He left Sydney on the Ceramic with other Dunera men, 50 of whom, Rothe included, transferred to the Stirling Castle in New Zealand. In 1942, the year after his return to Britain, he married. Was Miss Boxhorn the reason he returned as soon as he could, risking the threat of U-boats on the long journey from Australia? Possibly, though this isn’t certain. In 1949 he was married to a woman named Valerie Rothe, nee Ehrenzweig, born in Prague on 12 January 1905. Carol Bunyan, historian and demographer of the Dunera boys, believes that Valerie may have used the name ‘Ellen Boxhorn’ as an alias. Some information suggests this possibility, and it makes sense from a general perspective. Many refugees, then and now, opt for new names as a protective shield from past intolerance and future troubles.

There is no evidence that Rothe enlisted in the British forces. He worked as a commercial artist and in 1949 became a naturalised Briton. At this time he lived at 40 Clifton Gardens, London, W9. He stayed in England until at least 1951. The last sure evidence of his existence is an entry on the British electoral roll for that year. Elisabeth Lebensaft and Christoph Mentschl, historians of the Dunera boys from Austria, have found nothing to indicate Rothe returned there.

In April 1951 an artist named Hans Johann Rothe arrived in Sydney on the Blairclova. Was this man Hans Rothe, Dunera cartoonist? It seems likely, though as with so much about Rothe certainty is elusive. Signatures on immigration and internee forms indicate the same person, though the man who arrived in 1951 was said to be 5’ 8”, whereas Rothe was 5’ 11” according to a 1940 internee record. Another puzzle revolves around Valerie, Rothe’s wife. She died in England in June 1951, two months after Hans Johann Rothe disembarked in Australia. Would Hans Rothe, Dunera boy, have left England at that time? Did Valerie intend to follow him later? Did they separate, prompting him to move to Australia?

Hans Johann Rothe worked as an artist, in Sydney and possibly also in the Blue Mountains west of the city. The last years of his life were spent in the Blue Mountains. In 1972 he was resident at Queen Victoria Hospital, Wentworth Falls, an institution for the aged and chronically ill. He died at Wentworth Falls on 6 August 1973 and was buried nearby at Katoomba. A death notice published in the Sydney Morning Herald gave his age as 67. Hans Rothe, Dunera internee, would have been 68. Was the discrepancy in age a simple mistake? Who placed the death notice?

Many questions remain, and not just about Rothe’s post-war life. When did he leave Austria, and why? A sketch he did of the disorder and brutality of Kristallnacht suggests an eyewitness depiction: the drawing appears too raw and personal to have been otherwise (Dunera Lives, vol. 1, p. 15). The violence unleashed on Kristallnacht was wholly anti-Semitic, which makes it unlikely that the family depicted in the sketch was his own. What prompted him to chronicle the violence? Was he politically involved?

Some clues suggest that. His return to Britain in 1941 and subsequent release was authorised on the basis that he was known to have voiced public opposition to Nazism. His pre-war involvement with the Czech Refugee Trust Fund provides further hints. Among the non-Czechs helped by this fund were political refugees from Nazism who fled to Prague for sanctuary. As the fund was established in the European summer of 1939, Rothe must have gone to Britain in the second half of that year.

The National Library of Australia holds artworks by Rothe, as does the museum at Hay Gaol, which in 1940 served as a hospital for sick internees. Sometime between January and May 1941, Rothe gave three cartoons to Edna Solling, an Australian Army nurse stationed at Hay. In 1983 she donated the cartoons to the gaol museum.

We would be delighted to hear from anyone with information about Hans Rothe. As with so many Dunera lives, his intriguing story is worth telling.

With thanks to Carol Bunyan, Elisabeth Lebensaft and Christoph Mentschl for their expert knowledge and thoughts, Kate Garrett for help with translations, and Gabriela Schonbach for permission to reproduce sketches from her collection.

© The collection of Gabriela Schonbach

Author: Seumas Spark